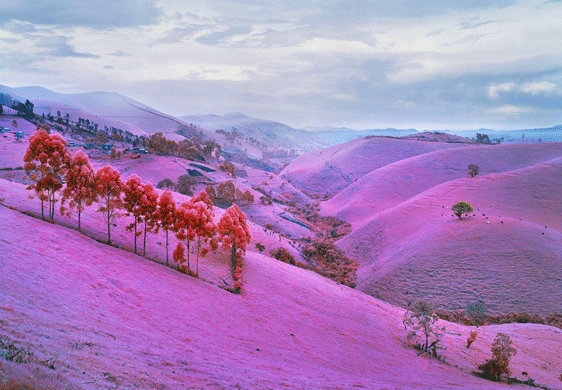

There has long been a tension that lies between photojournalism, art, and fiction. Seducing viewers through shades of searing pink and hot crimson in his photographs, Richard Mosse highlights that tension through the underlying subject matter of his series Infra. Entrancing and challenging, these images create an air of magical realism and portray a forgotten bloody conflict in central Africa in vibrant colour.

Born in 1980, Mosse is a contemporary Irish photographer based in New York. Having graduated from Yale University in 2008 with a Master of Fine Arts in photography, he went on to travel to the eastern Congo in 2010. This visit was motivated by his recent learning of the terrible impact resulting from the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Until then, little of this ongoing conflict had been covered by Western media, and understandably the artist was deeply troubled by the statistic of more than 5.4 million deaths since 1998.

Mosse, unhappy with documentary photography, wanted to push himself out of his comfort zone. He did this through his change of mediums, and also by travelling somewhere he had never been, knew no one, and didn’t speak the official national language, French. Challenging himself in this way, he was putting himself, knowingly, in a place where he would constantly be reminded of his inability to effectively communicate the ongoing crisis.

Capturing war-torn regions using a now outdated and extinct 16mm infrared film, Mosse’s technique is highly unique. Choosing this method allowed the photographer to make art through a highly intuitive process. It also enabled him to work as an artist in the places that journalists were working.

As an aerial reconnaissance film, Kodak aerochrome was originally developed for camouflage detection and transforms green into acidic pinks. While its purpose was to show possible destination points for aerial bombs, this film also benefitted other fields. Civilians such as cartographers, hydrologists, and archaeologists used Kodak aerochrome to show a landscape’s subtle changes. Capturing light that is invisible to human eyes, as is infrared, these individuals, through the use of this tool, made the invisible visible.

Mosse’s work represents the unrepresentable. With his practice straddling documentary journalism and contemporary art, he examines both the history of photography and that of Africa in relation to one another. Though necessary, telling these narratives of rebel groups fighting in a jungle war zone is not easily done.

Mosse, however, achieves this by completely rethinking how to depict such a complex conflict. Drawing the viewer into his photographs with unexpected, hyper-vivid colours, only after the initial glance does one travel deeper into the surreal images. It is at that point that individuals become aware of the surrounding warscape. These large-scale photographs (prints of being more than 6ft x 8ft) depict inhabitants, rebel army fighters, and the lush Congolese landscape and the effect of the conflict on each. The resulting images are powerful and highly cinematic.

Chronicling everyday life and trauma in these volatile regions, Mosse has made his mark on contributing to humanitarian awareness. This reflects the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16, on peace justice and strong institutions, in action. As an artist, he has shared that he is more concerned about consciousness than conscience. Much like how the psychedelic pinks and crimsons sear the viewer’s eyes, the images sear themselves into the viewer’s mind.

By sharing human suffering in such a way, Mosse aims to produce an ethical dilemma in the viewer, in this case, bearing witness to such crimes and increasing awareness through the disturbingly beautiful images.

More of Mosse’s work can be seen on his website.