African art spans centuries; it is rooted in recording deep spiritual beliefs and the tales and histories of its communities.

It encapsulates masks, ceremonial masquerade garments, vessels to communicate to gods, ornaments and thrones for the Queen Mother and her son. However, there has been minimization of the effect and influence which African art has had on the Western world, its perception of what art is and what we consider to be groundbreaking and genius. While the world is currently experiencing its first known taste of mainstream African culture influencing the zeitgeist, it has always been exposed to the art. Yet, many African artists have been unable to collect all their flowers for being the visionary dreamers and doers that they chose to be in their various climates.

This exclusion, lack of care and regard for African art resulted in a lack of recognition and achievements as well as a lot of unknown artists' works in museums. Contemporary African artists were always striving to create new ideas, new forms and new visual languages to push past the stereotypical traditional and historic category they found themselves boxed into.

This new language and the way these African artists pushed to be seen globally is usually referred to as African Modernism. It is a new territory that these artists created for themselves to speak and to be heard. It has taken some time for the rest of the world to acknowledge African artists and their contributions to the art world and art language that we are familiar with today. Though, it is because of artists like Ibrahim El-Salahi, who is featured in this article, that we are where we are now.

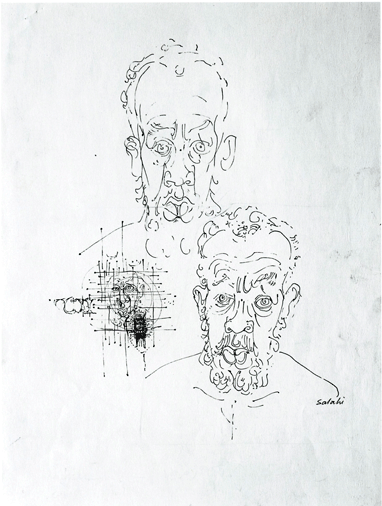

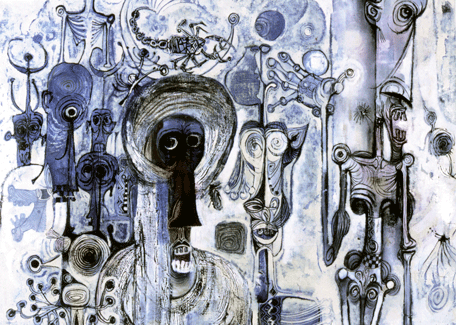

Ibrahim El-Salahi was born in 1930 in the historic city of Omdurman, Sudan to Muslim parents. El-Salahi has often said to be praying before beginning his work. He continuously explains that his practice of painting is a meditation, one that awards him less control of where the final finished work is heading. His art takes on many different styles, often leaving the viewer transcending into a spiritual realm, an abstraction of reality. He feels as though he is possessed when he is working, that some other power within him is producing that work.

El-Salahi’s work also draws from the Hurufiyya movement that is known in Arabic art, which stems from the late 20th century. Artists used traditional Islamic calligraphy and developed it within a sense of modernity to create a new visual language. These artists broke away from rules that governed traditional Islamic calligraphy used mostly devotionally and prohibited the representation of human beings.

Artists deconstruct Arabic letters, alter them and include them in their works. El-Salahi believes when working the artist should address first the self, the ego, then the second which are others, the people in your own culture, in your own family and in your neighbourhood and last of all, all of humanity, wherever it might be.

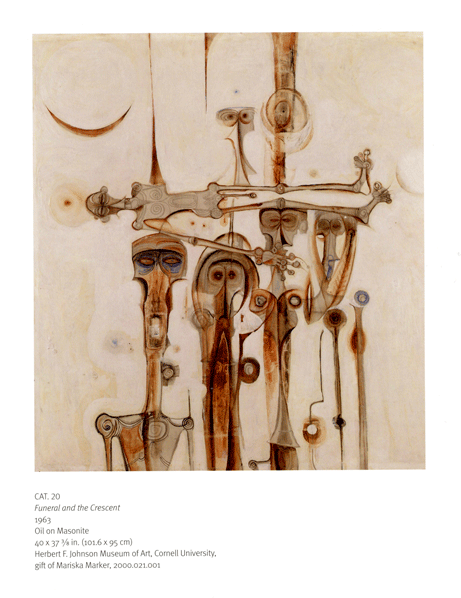

The colours that are most famously attributed to his works as a painter are the colours of the earth in Sudan; burnt sienna, yellow ochre, whites and blacks. He cares a great deal about his home country which is a strong influence on his work. His pieces combine Islamic, African, Arab and Western art practices. The Sudanese painter is known for his contribution to African Modernist art. He studied painting at the University of Khartoum (formerly known as Gordon Memorial college) in Sudan, he went on to study painting and calligraphy at the Slade School of Fine art at the University of London and later black and white photography at the University of Columbia in New York.

In 1975, Ibrahim El-Salahi was arrested based on the belief that he participated in a failed military coup. A cousin of his was responsible for planning the coup against Gaafar Muhammad Nimieri’s dictatorship and leadership of Sudan. Though he had no idea of his cousin's plans, he was asked to come in to speak to the head of security, which turned into a six month and eight-day stay without trial at the notorious Cooper jail in Sudan (now referred to as Kobar jail, where the 7th president of Sudan Omar Al-Bashir was sentenced in 2019).

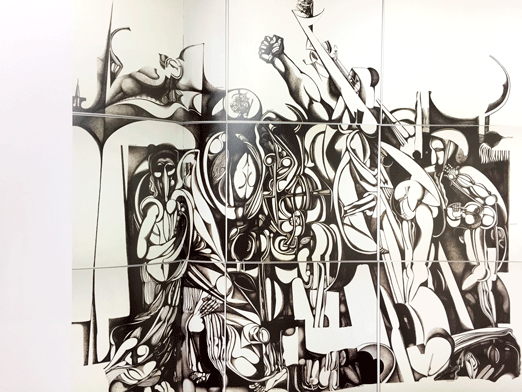

“I learned a great deal about myself in jail, to start with something which is a nucleus, and I have no idea what the outcome would be," said El-Salahi in an interview with Tate for his 2013 show Ibrahim El-Salahi: A Visionary Modernist, the first major retrospective of an African Modernist, which showed over one hundred works spanning five decades of his career.

"[It is] quite different to the Western concept of having a sketch, where you add and you omit this and that. No, I start with the nucleus which is completely unknown to me what it is going to grow up into. I must have been thinking about Sudan, about tyrants, I'm not a political animal but I have my own ideas about what should be done and what is good. People have got to shed away tyranny. People who are being pushed down continuously have got to rise up one day and liberate themselves.”

In prison, he used a sharpened toothbrush to draw the ideas of his future works in the sand, no pencils or papers were allowed in prison. He would always have to erase his work before the guards came and the exercise timeline was over. During this time, he would create his work The Inevitable.

The Inevitable became one of his most symbolic works of art, it signified hope within the people after the Nimieri government was overthrown. The painting tells the familiar tale of African endurance; that if the people persevere under tyranny, they can overthrow the powers that hold them down and back from the joyous and spiritual life they deserve. El-Salahi believes that The Inevitable belongs to the Sudanese people and he will only return the painting to Sudan when the people of Sudan have their human rights and freedoms restored.

Ibrahim El-Salahi’s contribution to art and the topics he cares so deeply about relates to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16; promoting peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, providing access to justice for all, and building effective accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels. El-Salahi’s practice as an artist led him to become the assistant cultural attaché to the Sudanese embassy in London in 1972. Later becoming the Director of Culture, and the Undersecretary of the Ministry of Culture and Information in Sudan until 1975.

The jobs in the Department of Culture required him to travel throughout Sudan, to find the sources of cultural heritage, to highlight, preserve and celebrate them. He led the delegation of Sudan to the first Pan-African Cultural Festival of Black arts in Dakar in, 1966 as well as the first Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers, Algeria in 1969.

These events contributed to the formation of the Pan-African art movements bringing attention to the African aesthetic taking place amongst artists in Africa and the African diaspora. El-Salahi took a break from making his own personal works during this time as the work was time and energy-consuming. He believes that artists should take advantage of well-established institutions so that artists can be left to their own devices, to be left alone to do their own work and see what happens.

El-Salahi spent his time as an artist working to create a community for African artists. The foundation of his practice to champion Pan-Africanism in art is something that has stayed amongst African creators and the fruits of their labour are something we bear when we can come together easily as young African artists working within the current arts sphere.