*This is part two of two of reflections in Art in Early Education

In Alberta, Canada, elementary education covers the years from kindergarten to grade six. The neighbourhood elementary that I attended in Edmonton from 2000-2006 had a teaching philosophy based on reflection and analysis, with a mandate to “look back, think ahead.” During my attendance, and continuing to today, the school has dedicated attention to its visual arts curriculum. Taught by the art specialist and French language teacher, Sharon Delblanc, art classes at the school are innovative and collaborative experiences. In a recent conversation I had with Sharon, she explained her approach to curriculum building: “My philosophy is that children learn to speak a visual language at an early age, and as with music, the earlier you can start to teach them to hear their creative voice and understand and develop their artistic skills, the better. I use a cross-curricular approach that integrates multiple subject areas to deepen learning and make connections.”

In February of 2000, the Superintendent of Schools addressed a letter to the Edmonton Public School Board of Trustees which articulated that “Today’s brain research suggests that arts can help lay the foundation for late academic and career success.” In addition, “Research has shown that by learning and practicing art, the brain actually makes more and stronger connections. Art stimulates body awareness, creativity and a sense of self.” At this school, art education has long been valued as it means “to teach thinking and build emotive expressiveness and memory.” Parents and community members contribute their hands, wallets, and time so the school can gain access to extensive materials. Developed lessons and access to advanced mediums make classes different from typical early education art courses; tempera finger painting and colour mixing do not constitute class projects. When I was a student, materials included access to kilns for ceramic and glass making, film cameras for photography projects, charcoal for still life drawings, and more.

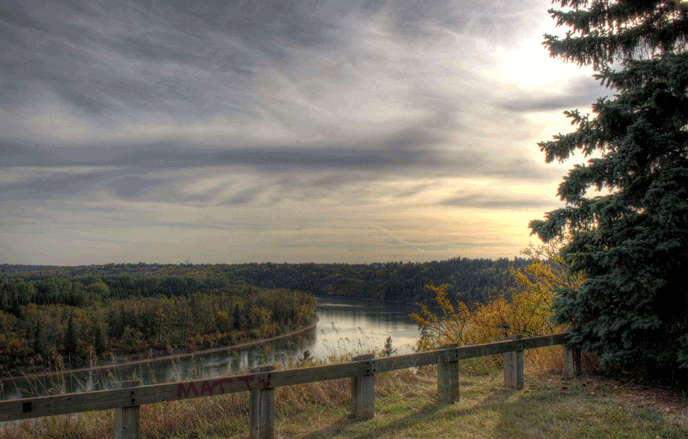

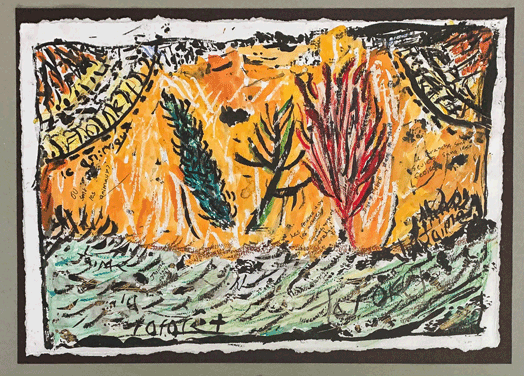

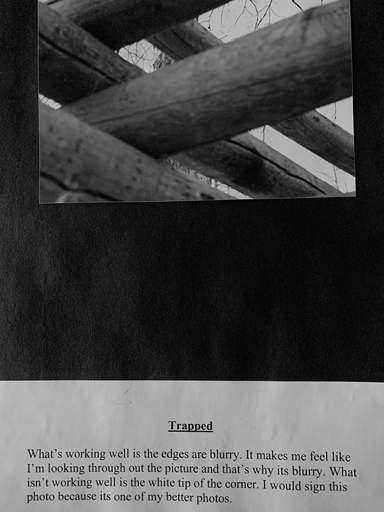

Each new project and exploration of a medium built the last. For example, one project required students to adapt to the same composition through various mediums. Students chose one black and white photograph, taken on a class adventure to the Edmonton River Valley, as a reference source. The images were transformed into pastel drawings and watercolour paintings that included French poems about students’ experiences by the river. These completed multi-media pieces became reference points for glass mosaics that students created with the help of adult volunteers. Reflecting on my time at the school, I realize that the range of projects I completed, the mediums of art I explored, and the unconscious learning skills I adopted from exposure to the curriculum are comprehensive.

As an educator, Sharon believes in using formal artistic language, terms, and materials to honour the importance of a child’s work. She articulates that “Each child is born with a unique creative voice,” and her role is to help a child develop their voice by teaching skills and techniques that enable them to explore and express themselves in a visual world.

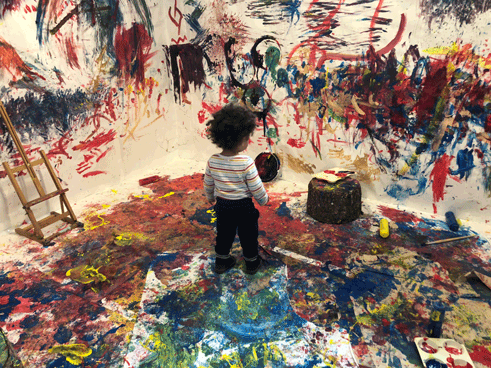

Researcher Louisa Penfold believes materials are active forces for learning, arguing that “As children play with materials, they learn about their physical properties and what these materials can do in the world… A material’s sensory and aesthetic properties may also transform as a child plays with it, generating further experimentation opportunities. These transformations then allow children to extend and make their learning more complex over time.” The projects developed by Sharon worked to build a knowledge of synthesizing relationships between environments, language, mediums, and histories. Rather than focusing on creating “ideal” artworks, students, regardless of their abilities, gained comprehensive skills to critically analyze the symbolism and physicality of the world around them.

Exposure to early arts education can provide individuals with tactile and analytical skills to carry and utilize throughout their lives. The comprehensive nature of these skills makes them transferable among various aspects of life, career choices, and social situations. Nick Rabkin bolsters various links between visual arts and general student achievement –– drawing can support writing skills, visualization can support interpretation, and so on. According to The Education Hub, arts education facilitates communication, mediates thinking, encourages diverse points of view and cultural knowledge, fosters an understanding of identity, promotes creativity, and develops critical literacy.

Critical thinking is the “process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication…” Thinking critically is a beneficial attribute for postsecondary students regardless of their chosen field or industry as it helps to build and practice knowledge. Within postsecondary education in the arts and humanities, critical thinking is essential for students to maintain and understand as analysis, self-learning, and evaluation are deeply integrated into these subjects’ curriculums.

Having completed two post-secondary degrees (a BFA and MA) in visual arts and humanities, I know the importance of analytical skills. Analyzing, evaluating, and communicating have been efficient methods for me, as a student, to develop a resonant knowledge of visual art, history, and writing, as well as the philosophies that surround these subjects. I use my artistic skillset to process information regularly, make everyday decisions, and navigate life matters. The foundation set by these critical skills, which I attribute to my early arts education, has helped me succeed, continue to grow as an individual, and learn as my life and career advance.