Over-complicated mentions of affect theory constantly punctuate conversations surrounding art. The art world dedicates itself to capturing emotions and feelings, especially affects, which are essential to communication and understanding. Originating from the Latin word affectus, meaning disposition, affect is pre-personal, and the type of experience it involves is nonconscious. Individuals are often unaware of affect as it is experienced, which makes it difficult to pin down and describe with words alone. In this way, affect differs from emotion. Whereas emotion is very much a personal experience that involves feeling, affect theory does not. With this limitation in mind, this concept of affect precedes cultural emotions and personal feelings.

Works of art and their ability to generate a nebulous concept of affect are rooted in the contemporary understanding of audience and artist. To produce affect, there has to be an object of attention. Specifically, there needs to be something to which viewer engagement links to, and is often an individual painting, sculpture, or other such visual artwork.

Different experiences of ‘affect’ occur independently from cognition and reason (and thus thought and meaning). These affects occur freely, as they surpass the limits of the human subject. Affects exist as active exchanges between materials and humans, a conversational relationship that arises regardless of viewer intention, merely being in a space with artwork demands meaning. In this way, affect does not always fall within conscious thought.

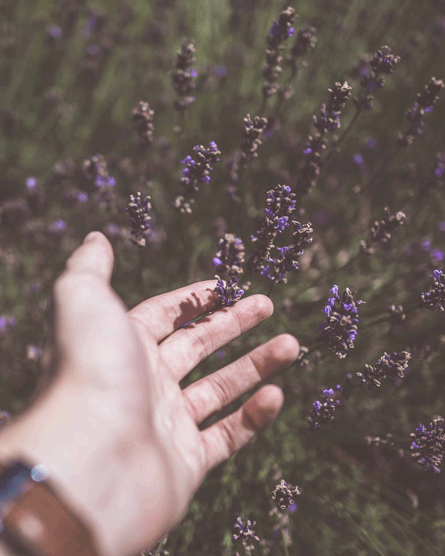

Affect-involved works address the spectator in multisensory ways, an element of the theory that is often overlooked. Looking at affect theory through a sensory lens is what often makes this theory easier to grasp. The olfactory experience, or smell, is an effective outlet, to begin with. Sense of smell necessitates close contact and therefore puts the viewer and audience in proximity. Once an individual exposes themselves to a scent, it is difficult to control their response. From this uncontrollable connection comes the concept of affect. Smell facilitates a strong connection to memory and creates experiences beyond personal control; it can introduce foreign elements or catapult viewer’s into deja vu. Generating experiences beyond one’s control is precisely how affect theory operates.

Power often associates itself with affect theory. In this case, power comes from affect’s ability to act as a “thing of the senses.” It is through this consideration of power that affect theory evolves into something beyond human control and comprehension. There is an indescribable factor of experience, one that permeates all of humankind yet often evades language. In this way, one can understand this theory as something that, rather than linked to rational thought, linked to instincts and the experience of living.