*This article is part of Arts Help's Art Theory series.

The concept of feminist art as a genre originated in the 1960s and 1970s in association with the feminist movement in North America. The objective of feminist art as a genre is to explore gender disparity in service of positively influencing the societal limitations placed on women, and to promote equality while challenging the outmoded norms associated with the female gender. This goal manifests in the act of highlighting various forms of systemic injustices towards women, whether they be antiquated societal standards, or dangerous, passive, and aggressive attitudes that act to suppress or destroy women’s freedoms. Feminist art can also be used to subvert these destructive standards thereby calling into question their validity and true nature, and can be used to empower women, working as a means of celebrating women’s triumphs, perseverance, and autonomy. As a methodology in art theory, feminism acts as a lens through which to view and critique art with consideration for negative biases towards women, how the meaning of that information affects culture, and the way in which people are influenced as a result.

Feminist Art as a Response

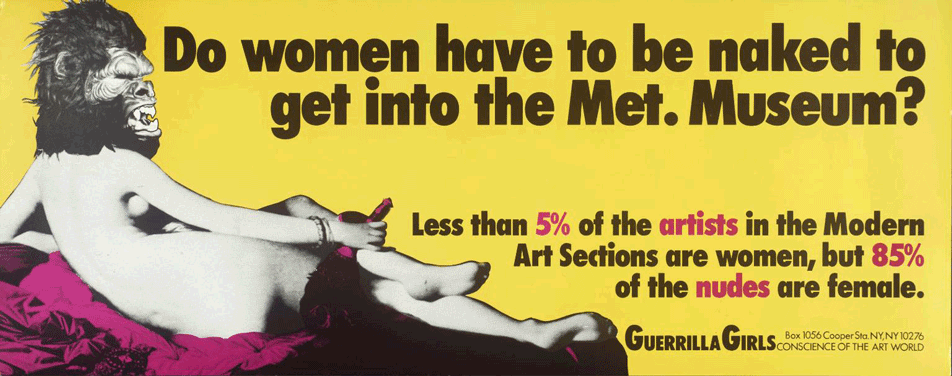

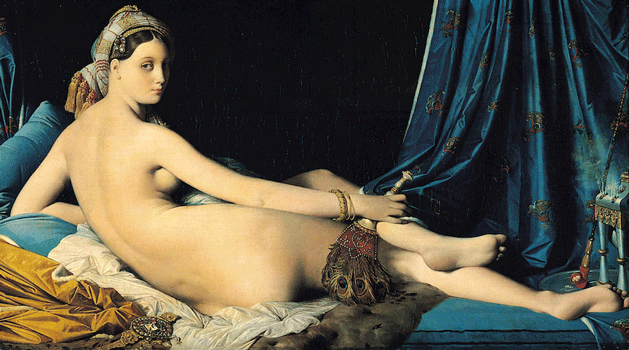

Perhaps the most recognizable collection of feminist art is that of the Guerilla Girls, as their mass-media approach to making art and their rallying content provide explicit and easily attainable meaning. The anonymous group of feminist artists called the Guerrilla Girls formed in 1984 in response to a large exhibition held in the same year at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in which less than 10% of the 169 artists featured were women. In 1985 the group began a poster campaign meant to highlight the disparity between male and female representation in both the art market and the cultural sphere. Among the more famous images is Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get into the Met. Museum? (1989). Originally commissioned by the Public Art Fund in New York but rejected after completion, the Guerrilla Girls self-funded the campaign by running the piece as an advertisement on New York City buses. The bus company soon cancelled the lease of advertising space for the image, citing that it was too suggestive as the figure appeared to be holding a phallic object in her hand. The image is based on the Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1789-1867) painting La Grande Odalisque (1814) – though in Turkish “odalisque” means “chamber attendant,” the word became used to describe an 18th century Western genre of painting that featured an eroticized woman laying passively on display for men to observe. The Guerrilla Girls’ appropriation of the image satirizes the institutional service to the male sexual gaze, with the poster’s text reading, “Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.”

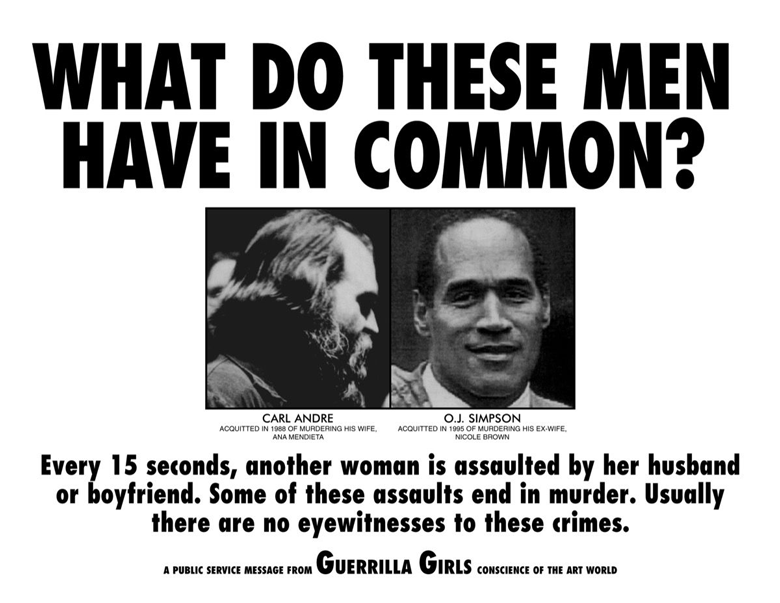

While the treatment of the female nude in art history raises issues of the objectification and subjugation of women, the consequences of those misogynist attitudes were made specific in a 1995 Guerrilla Girls poster, What Do These Men Have in Common?, referencing the cases of two famous men acquitted for murdering their wives. One of the fundamental issues addressed in feminist theory is the perception of women’s roles as considered only in relation to me, rather than viewing women as self-possessed individuals. tThe negative outcome of these attitudes presents at worst in the form of violence against women, particularly in a domestic setting due to a sense of ownership and superiority. In the case of the innovative multimedia artist Ana Mendieta (1948-1985), many groups believe that her husband, minimalist sculptor Carl Andre, murdered her by throwing her from their 34th floor apartment in 1985. Andre stated in the call made to 911 that he and Mendieta had been fighting: “I went after her and she went out the window.” People in the building testified to hearing violent fighting in the moments leading up to the incident, including a woman’s voice shouting “No!” and Andre was found with scratch marks on his face and arms, but with no eyewitnesses on the scene, the judge acquitted Andre due to reasonable doubt. Many people consider this result an injustice and have spoken out to raise awareness of Mendieta since her death, not only as a victim of alleged spousal homicide and domestic violence, but as an important modern artist worthy of recognition.

Feminist Art as Empowerment

Several formal protests have erupted after Andre’s acquittal and Mendieta’s lack of representation in the major museums. Most recently, protesters under the group name WHEREISANAMENDIETA marched outside the Tate Museum in New York in 2016 in protest of Andre’s inclusion in a newly created wing of the gallery, while Mendieta’s work remained absent from the exhibit. The group, along with many art critics and historians, believe that Mendieta’s legacy should be revitalized to foreground her remarkable contribution to art rather than the tragic circumstances of her death.

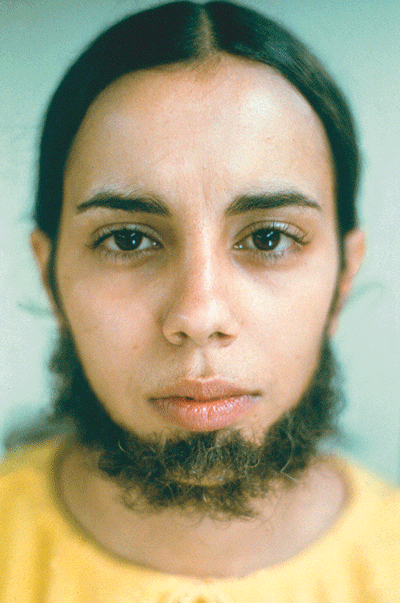

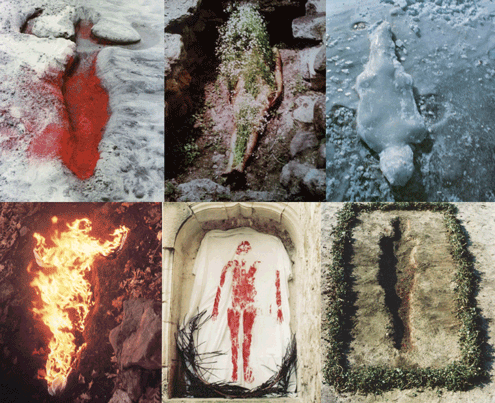

In support of her artistic merit, curator and writer Jared Quinton stated of Mendieta’s influence: “Fusing art and life, Mendieta took risks, experimenting with performance and other unconventional mediums at a time when the market had no interest in them.” During her brief career, Mendieta challenged notions of gender, memory, identity, belonging, and life-force, explaining that, “my art is grounded in the belief of one universal energy which runs through everything.” This notion is expressed in many of her earth-body art performance pieces, such as Silueta (1975) and Tree of Life (1976), and in her conceptual body art, such as Untitled – Facial Hair Transplant (1972).

Although Mendieta never categorized herself as a feminist artist, she championed equality through her work, and exposed certain adversities of the female experience, with very little recognition from the art world at the time. Performance artist Coco Fusco asserts that the “post-mortem canonization” of Mendieta is problematic, especially considering the negation of her work in favor of using the idea of the slain artist as an emblem. While the circumstances surrounding her death should never be discounted, the recent attention to Mendieta seems to be shifting in the direction of her art and life. As auction house chairman August Uribe posits, “the globalization and internationalization” of art, as well as the art world’s overdue interest in female artists, has led to the discovery and celebration of Mendieta’s work. After a long absence from representation in the art world, the resurgence of Mendieta’s work continues to grow, with private collectors and museums showcasing her documented performances, and contributing to the discussion of Mendieta as a person and an artist.

Though brought to light and into the academic art lexicon in the late 20th century, feminist art and critique extends far beyond the scope of those decades, and continues to evolve the discussion of equality, perception, and progress. For more information and resources, please visit the Feminist Art Coalition and the Feminist Art Collective.