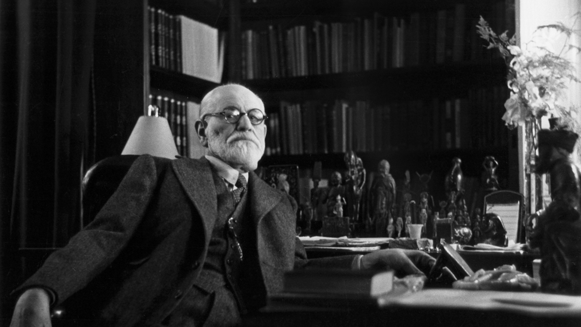

Since its establishment in the early 1890s by Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), psychoanalysis has run a parallel track to the study of art. In essence, both art theory and psychoanalysis are the study of images – real and imagined – for the sake of rooting out a deeper meaning. Until Freud’s theories of the unconscious mind, however, the study of art history and the discussion of images was almost exclusively in reference to the finished product of the image. It was not until 1910 that Freud wrote the first account of psychological art theory, and with the bridging of the gap between art criticism and psychoanalysis, scholars began the discussion of art as a process of revealing unconscious motivations and hidden meanings.

A Brief History of Psychoanalysis

Psychoanalysis, from the Greek meaning “to investigate the soul,” is the theory that human behaviour is largely determined by often-forgotten childhood events and deeply rooted instinctual drives, and most major actions stem from these sources. Freud argued that mental disturbance and patterns of destructive behaviour are caused by the repression of those drives. The locus of unhealthy thought patterns or behaviour, when hidden or misunderstood by the subject, must be revealed in order to be repaired – and to be revealed, the subject must be willing to undergo treatment. The theory suggested that a person often signalled their unconscious through dreams, mannerisms, and subtleties of speech. Adequate treatment therefore involved the analysis and interpretation of personal interviews as part of what Freud called the talking cure – now simply called therapy. Though many controversial facets of psychoanalysis have gone into decline since their inception, the structure of Freud’s work formed the building blocks for modern psychology, contributed to the study of visual art, film, literature, and fairy tales, and has forever changed the way people think of the human mind.

Art and Psychoanalysis

In 1910 Sigmund Freud published an essay called Leonardo da Vinci, A Memory of His Childhood, in which events from Leonardo’s youth are interpreted as motivation for his paintings creating the first known work of art historical psychoanalysis. The essay in part discusses Leonardo’s painting The Virgin and Child with St. Anne; Freud suggests that because Leonardo was “illegitimate” and raised briefly by his biological mother before being adopted by his father’s wife, the painting depicting two mothers was of particular significance to the artist. As an example of the unconscious manifesting in the art, both the Virgin Mary and her mother, Saint Anne, are painted to look similar in age, when in fact there should be a generation between them. This type of investigation sparked the development of psychoanalytic methodology in terms of art, and can be divided into three frequently overlapping categories: psychobiography, or the study of the artist’s life as specifically influential to their work; psycho-iconography, which is evident in the use of conventional symbolism but also interpreted with the artist’s motivations in mind; and the origin of creativity, having to do with the artistic process and how the artist arrived at the choices they made through various influences. While the polarizing effect of the highly subjective practice of psychoanalysis of art drew heated debates between art scholars in its early years, the impetus of this method has always been unifying. Freud loved art: his concept of ideational mimetics posits that original artwork offers an exchange of energy between the viewer and the art, often referred to as the aura, and that this energy is paramount to the human condition. The effect of art, according to Freud, was fundamental to empathy, and a necessary part of any civilized society.

Psychoanalysis and Surrealism

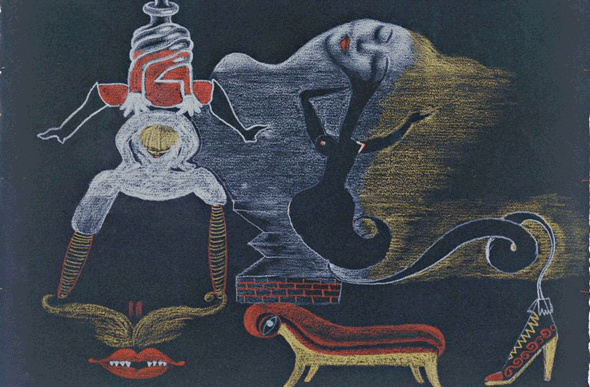

The Surrealist movement, beginning in the early 20th century, first took shape partly in response to Freud’s canonical text, The Interpretation of Dreams (1899). The notion that dreams held keys to revealing inner consciousness through symbolism of hidden desires, sexual personae, forgotten events, and even the truest nature of the dreamer, was particularly enticing to the Surrealist artists. The movement came to adapt psychoanalytic tools like free association and stream of consciousness as methods for creating art that unveiled things hidden in the unconscious mind. These practices involved automatic drawing, the process of creating marks and images without conscious intention, or as Surrealist principal Andre Breton (1896-1966) described, “Thought expressed in the absence of any control exerted by reason, and outside all moral and aesthetic considerations.”

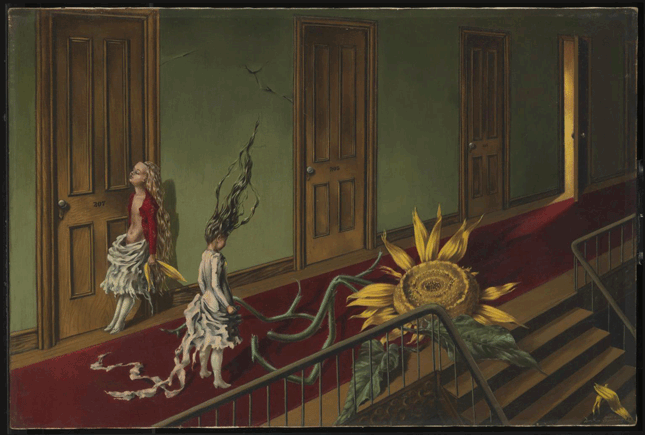

Surrealist painter Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012), for example, painted many works inspired by dreams for the purpose of expressing her truest nature. Her painting, Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943), named for a chamber music composition by Mozart (1756-1791) that was popular in her social circle when she first began painting. As a whole, Eine Kleine Nachtmusik is a symbolic tableau of youth, featuring the supernatural elements of nightmares and Gothic fiction that Tanning remembered from her childhood. The living doll on the left slumps against the door jamb in apparent ecstasy, having plucked a petal from the sunflower, according to Tanning, “[the] most aggressive of flowers.” The girl next to her is dressed in tattered clothing similar to the doll, suggesting a struggle, and her hair is swept upwards, the result of an impossible gust of wind or force of gravity. Tanning was adamant that this painting was not to be compared with anything quantifiable, and that the sunflower was a symbol of the things that, “youth has to face… the never-ending battle we wage with unknown forces.” The open door at the end of the hall reveals light, at once a beacon of hope and treacherously unattainable mystery.

The interpretation of art based on the practice of psychoanalysis is one of the most pivotal developments in art history. To view art not as material, but as evidence of the most inaccessible features of the mind transcended art into the realm of endless philosophical possibilities, as complex, frustrating, and challenging as the mind itself.