Currently residing on Vancouver Island, but originally from Burlington, Ontario, video artist Kelly Richardson makes work that revolves around the installation of ethereal moving image pictures. Capturing videos and producing images through high technology cameras and programs, her installations depict scenes of the world’s land––forests, lakes, and skies––to elusive imagery of what lives beyond the earth––the moon, other worldly environments, and the future potentials of life. Richardson completed a Bachelor of Fine Arts at Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto as well as an MFA in Media Arts at Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax and New Castle University in North East England. In 2017, she became a professor at the University of Victoria where she still teaches in the Department of Visual Arts.

Richardson’s art encourages people to look more closely at elements of nature, ecosystems, and human relationships with the planets’ diverse environments––asking individuals, in a magical and beautiful manner, to reflect on how they can make substantive change in the way that they interact with the planet. She has articulated that, “Art has the ability to engage people on an emotional level.” Through her work, Richardson entrances the emotions of her viewers, believing that, “People act when their emotions are triggered and that’s where art can come in,” to help inspire real efforts towards sustainable change for the planet’s health and sake. This is precisely the emotional engagement policymakers and activists try to attract the public with in order to put the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially goals 13, 14 and 15 on Climate Action, Life Below Water and Life on Land, into action and create a world where humans and nature coexist.

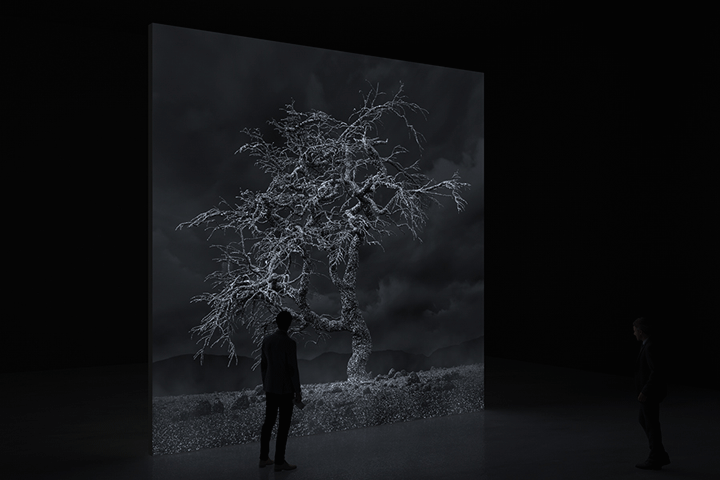

In a 2011 exhibition review for Canadian Art, Shannon Anderson expresses that, “Time after time, Kelly Richardson’s videos feature intensely beautiful landscapes interrupted by a disquieting presence that shifts everything toward the hyperreal.” Richardson’s works teeter between representations of fiction and reality. She regularly combines the aesthetics of documentary cinema and science fiction films and believes that as a creative genre, science fiction allows humans to imagine what the future of life on earth might be like. Her 2010 three-channel video installation, The Erudition, for example, depicts real scenic views “set in the Alberta Badlands,” alongside “a gathering of holographic trees.” Richardson describes The Erudition as “a lunar-esque looking landscape with what appears to be an unlikely monument or proposal, consisting of holographic trees blowing in fictional wind. Is this slightly malfunctioning display a forgotten site for proposed colonization? Better yet, is this some kind of alien artwork?”

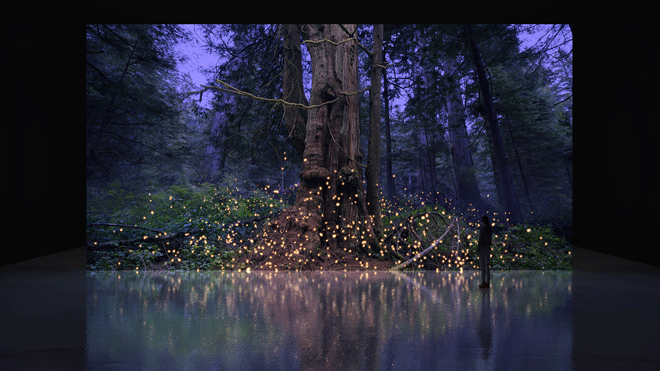

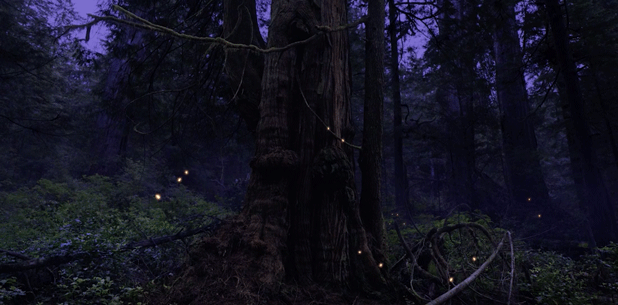

Richardson’s recent video work, Embers and the Giants (2019) “is an IMAX commission,” that was filmed with 2 out of 7 of the world’s IMAX cameras. Around the time of Richardson’s shoot, various IMAX cameras were used to film movies like Wonder Woman and Avengers. IMAX cameras are a Canadian large-format invention which record video and image with “huge dynamic range and a spectacular color rendition.” Embers and the Giants chronicles “a complex old-growth rainforest here on Vancouver Island,” located on the territory of the Pacheedaht First Nation, who granted Richardson, and her crew, permission to explore and film the land.

As Richardson describes concerning Embers and the Giants, “In the forest appears to be thousands of floating embers of light.” While watching, a viewer “might assume that they are looking at fireflies, but as they watch, they notice that something is not quite right…” They soon realize that “Perhaps they are looking at thousands of tiny drones.” In this work, Richardson aims to imply that there may come a “time in the future when we have to amplify the spectacle of nature…artificially, in order to convince the public of its worth.” In real life, areas like this land and other lands around Vancouver Island are popular tourist destinations and old-growth trees “are remnants of industrial logging. For Richardson, the film raises a question that touches a core of SDG 15 concerning Life on Land; “in light of the terrifying fallout of continued, large-scale biodiversity loss worldwide, when are vital ecosystems worthy of preservation?”

As a whole, Richardson’s evocative and compelling practice puts forth the idea that we don’t know what our future will look like given the current rate of environmental change and destruction happening on our planet. She expresses, “What I want people to take away from this world, along with all of my work, is an appreciation for where we are heading and why.”