Antonio Vega Macotela’s installations create a striking juxtaposition of 18th-century Bolivian silver mines, environmental activism and capitalist malpractices.

Taking inspiration from an infamous group of 18th-century Bolivian pirate miners, the Q’aquchas, Antonio is currently working on a long-term project titled The Q’aquchas Ballade. The Q’aquchas inspired numerous other installations, namely Mill of Blood and Study of Exhaustion — The Equivalent of Silver.

Nobody will believe the fire, or Incendio as it was titled at the CIAP exhibition in Belgium in 2019, is the first chapter of the larger The Q’aquchas Ballade series.

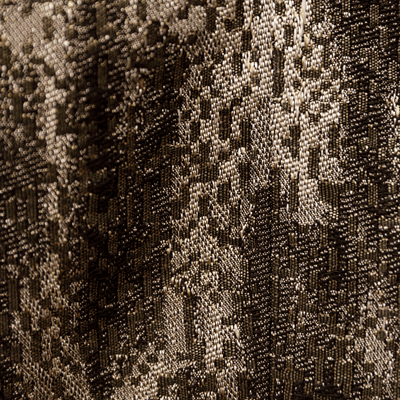

Incendio, meaning fire in Spanish, comprises seven large-scale tapestries, each depicting wildfires. Not only is it an analysis of the growing concerns for environmental degradation, Incendio holds layers of meaning within the tapestry itself.

Antonio gathered a collection of low-resolution images of wildfires from the internet. He then contacted one of the most powerful hacker groups in the world, led by Nos del Abismo, for a collaboration. Antonio used Jacquard looms to transform the wildfires print onto the textiles.

The Jacquard loom itself has a close affinity with computing hardware technology. It uses replaceable punched cards, which are pieces of stiff, and perforated paper that contain digital data in an analogue format. Punched cards were at the forefront of revolutionizing computing hardware systems.

The tapestries also serve as a data-storage unit. Each pixel printed onto the tapestry is encoded with information from the ‘Lagarde list’. The Lagarde list, a subset of the ‘Falciani list,’ contains names of about two thousand tax evaders of Greek nationality which was released in 2010, at the onset of the Greek financial crisis.

By using digital steganography, commonly used by hackers and activists to hide secret information in an ordinary file, Antonio encodes data into the images of wildfires. In digital steganography, information is stored in minute colour or luminosity variations which are imperceptible to the human eye. Antonio purposely exaggerated the tonal variation to shades of gold in Incendio to make those patterns visible to the viewer.

By encoding data onto wildfires, Antonio suggests a connection between manipulative politics and climate crisis; neither of which seem to be solved, or encoded, by the people in power.

Antonio’s decision to use wildfires can also be a response to the amalgamation of 19th-century nationalism with Romanticism. The forest burning correlates to the rapid deforestation caused by the industrial revolution in the 19th century, and the depletion of more forest area by warfare in the subsequent centuries.

Incendio highlights the United Nations Life on Land, and Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions Sustainable Development Goals. Not only do political organizations need to check their own power, but also the effect of their laws and regulations on the earth and people whose livelihoods are dependent on land. Similar to the Q’aquchas exploiting the Bolivian silver mines, modern forms of labour laws also exploit workers, especially marginalized communities all across the world.

In the economy of digital data, physical borders present no threat to the powers of nation-states and the corporate world. As the transfer of information remains invisible to human perception, the transaction of power presents a palpable effect on the landscape, livelihood of people and the poor workforce.

The critique of the invisible workings of the exploitive system also resonates within the title of the series itself, Nobody will believe the fire if its smoke does not send signals. This is a quote from the poem Incendio by sister Juana Ines de la Cruz, a Mexican poet of the Q’aquchas. An excerpt from the poem is as follows:

“Salgan signos a la boca

de lo que el corazón arde,

que nadie, nadie creerá el

incendio si el humo no da señales.

(May signs come out of my mouth

of how much my heart burns,

Because nobody, nobody will believe a

fire if its smoke does not send signals.)”

Antonio tells Labor that “art is significant, it is symbolic. The actions that affect society are also symbolic and the work of the artist lies in working with those symbols and those meanings. It is about expanding wills and generating possibilities to see and think.”

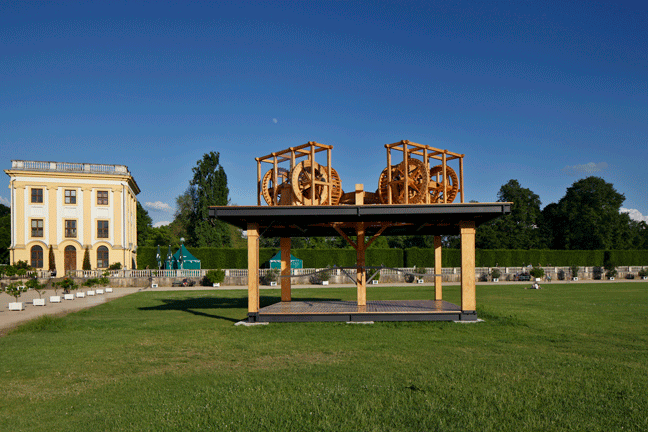

Antonio’s Mill of Blood, and Study of Exhaustion — The Equivalent of Silver also examine the exploitation of slave workers.

The Mill of Blood is a full-scale replica of an early Spanish-colonial silver mill in Bolivia and was worked by slave labourers. The coins produced in Antonio’s reproduction do not feature the usual head of state but the feathered horn of the Bolivian god of mines: El Tío.

Part of the plaque on the installation reads: “Wealth was not only extracted from the earth but also from the bodies of indigenous peoples. [...] Contemporary Bolivian miners, whose average lifespan is forty years, provide food and other offerings to El Tío even today, whose spirit, in turn, protects them. The coins are pocket monuments.”

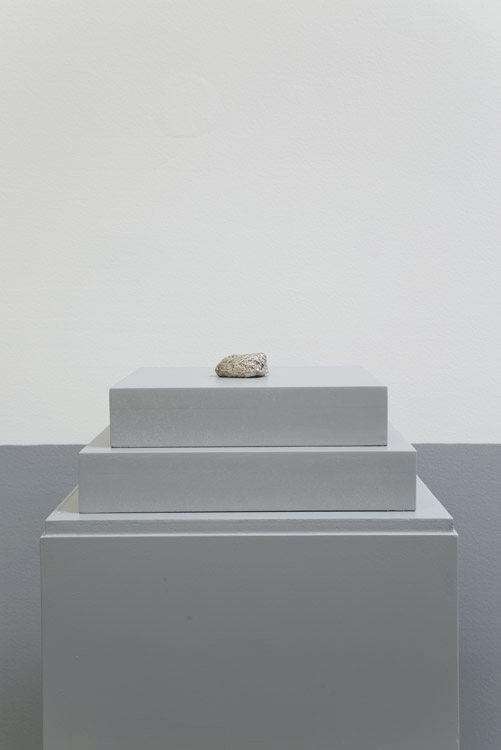

Study of Exhaustion — The Equivalent of Silver mocks the silver mining industry’s poor working conditions, especially in 18th-century Bolivia. The installation comprises a tiny silver ball. The size and shape resemble a “wad of coca leaves” chewed by a Bolivian silver miner during the course of his shift. Coca’s analgesic effects help the miners to work for longer hours with fewer breaks.

Antonio has been selected to participate in the 34th edition of São Paulo Biennial (Brazil), “Faz Escuro mas eu canto” (Though It’s Dark, Still I Sing), opening in September 2021.