Carrie Mae Weems is an influential African American artist most renowned for her visually compelling photography that combines text and audio to capture the particularities of past and contemporary African American life. Born a woman of colour in the United States of America, Weems has invariably been concerned with questions of power and its relation to cultural identities formed by race, class and gender. Investigating the politics of spatial accessibility that may invite or exclude, Weems creates apposite yet seminal moments of racial and gendered representation.

The kitchen is a space of nurture and nostalgia—known for binding subjects in shared experience and offering respite in the midst of struggle. In The Kitchen Table Series (1989-90), Carrie Mae Weems foregrounds the kitchen, a familiar space residing in the domestic sphere, through storytelling and a series of intimate contemporary black and white photographs reminiscent of film noir, to record the unfolding of fictional, yet universal and prevalent occurrences.

“Weems’s black-and-white photographs are like mirrors, each reflecting a collective experience: how selfhood shifts through passage of time; the sudden distance between people, both passable and impassable; the roles that women accumulate and oscillate between; how life emanates from the small space we occupy in the world,” writes Jacqui Palumbo.

In the iconic series, Weems positions herself at the kitchen table, which features shifting iconographic objects such as wine, cigarettes, books, a deck of cards and chocolates, depending on which companions, be it solitude, or be they women, children and men who join her at the table. There is a facilitation of visual intimacy between the cast of characters and the audience, as the photographs appear to grant viewers a seat at the table, in the midst of Weems performing scenes of social interaction and family life to create narratives of (unrequited) love, loneliness and liberation.

The kitchen is perceived as a space for the subculture of women—a place of invisibility where women experience domestic joy and domestic bondage concomitantly. Weems’ photographic series can thus be interpreted as an extended metaphor, capturing the making and unmaking of women, particularly African American women, in the home space. By disorientating and reorienting the domestic commonplace of the kitchen, Weems visually communicates the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of Gender Equality through meaningful yet complex identities of women, by drawing from and then transforming fixed cultural ideas about race and gender identity.

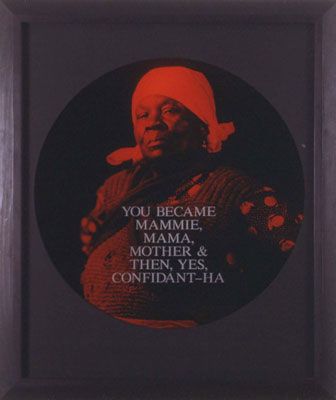

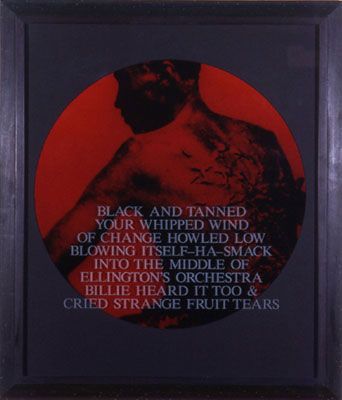

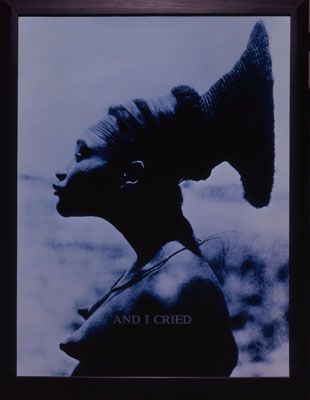

From Here I Saw What Happened, and I Cried (1995-96) uses archival images of slaves dating back to the 19th and 20th centuries. Accompanied by a photographer, Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz travelled to the American South with the intention to create visual evidence, from the portraitures of slaves, to corrobate anthropological theories about the racial inferiority of African Americans. After acquiring this series of daguerreotypes, Weems felt inclined to subvert the former instrumental purpose of these colonial archives by rephotographing, enlarging and laminating the existing photographs with text and striking monochrome colours of red and blue to synthesize narratives of both Black history and photographic history in the United States of America.

In offering a more emotional African American perspective, From Here I Saw What Happened, and I Cried reveals how the medium of photography supported claims of white superiority and shaped racism by violently reinforcing racial stereotypes. Through the series, Weems unmasks the profound social injustices rooted in relations between white subjects and non-Western populations of colour classified to bias ideology, making the series an expression of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions.

“Black people are to be turned away from, not turned toward—we bear the mark of Cain. It’s an aesthetic thing; blackness is an affront to the persistence of whiteness. It’s the reason that so little has been done to stop genocide in Africa. This invisibility—this erasure out of the complex history of our life and time—is the greatest source of my longing,” says Weems in an interview with BOMB Magazine.

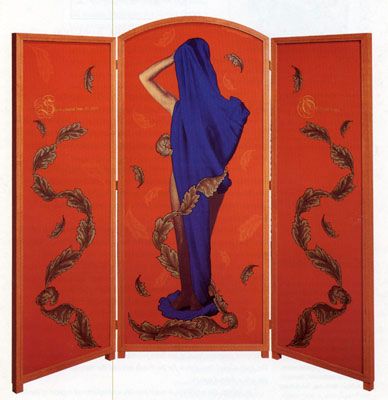

The Africa Series (1990-93) is a collection of photographs taken by Weems during her first trip to Africa when visiting the coasts of Ghana, Senegal and the city of Djenné in Mali, considered to be one of the oldest urban sites in Western Africa. Weems was intrigued by the configurations of ancient architecture that appear to suggest specific gendered space through male and female traces of human anatomy. The series forms a record of physical places and cultures, chronicling settings imbued with the historical remnants of slavery.

Carrie Mae Weems situates herself both in front of and behind the camera in many of her photographs. Specifically, when women situate themselves behind the camera, they take up a position that has traditionally been white and masculine. Another element of Weems’s work centers around conversations about Blackness and returning the dignity and humanity taken during the colonial era, to various victims of enslavement. Through Black female subjectivity, Weems creates work for and about (Black) women and to a larger extent, for people of colour. The bodies of work made by Carrie Mae Weems have not only reclaimed, but exhibit a form of female authorship and agency that is both poetically intricate and critically self-aware.

See more works by Carrie Mae Weems on her website.