In partnership with The Global Goals for #BlueToDo, an initiative raising awareness of the importance of a healthy ocean, Arts Help will publish a series of interviews highlighting artists that combine their creative minds with their passion for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of Life Below Water.

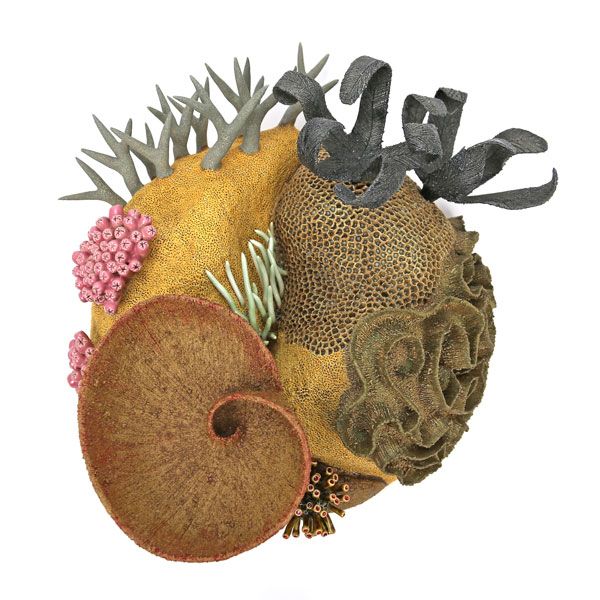

Growing up in the San Francisco Bay, Courtney Mattison developed a love for the ocean from a very young age. With a degree in marine ecology and ceramic sculpture, the now full-time artist combines her two passions to create magnificent large-scale ceramic sculptures of coral reefs that aim to raise awareness of the effects of climate change.

In an interview with Arts Help, Mattison elaborates on the motivations behind the creation of her pieces as well as the importance of maintaining a healthy ocean.

You were born in San Francisco, and you have a Bachelor of Arts degree in marine ecology and ceramic sculpture. It sounds like you had a vision of what you wanted to do from a young age. How did your love for art as well as marine life start?

I did get an early start in figuring out what I wanted to do with my career. I grew up in San Francisco and I was always really fascinated by the sea. Living along the California coast, I just loved exploring the tide pools. My mom would let me peek inside crab traps along the coast of San Francisco and in the Bay, and it fascinated me that there were these kind of alien-looking creatures, especially marine invertebrates, that were so strange-looking but also right in our own backyard.

I think I’m a visual learner, I’m kind of a three-dimensional learner, and when I was just getting started it felt really natural for me to try to sculpt the creatures that I was fascinated with. As soon as I started studying marine biology in high school, actually when I was about 17 years old at San Francisco University High School, I started sculpting marine invertebrates in ceramic, so I really did get an early start, and it kind of snowballed from there. After high school, I got scuba certified and then really dove in, literally, into studying marine biology in college, and I studied for a semester on the Great Barrier Reef at James Cook University in Australia.

All throughout that process I was creating art. I did a master’s in environmental studies at Brown University [which is] really a social science degree, so I was doing interviews where I asked marine researchers and also artists inspired by the environment what the potential was for art to inspire coral reef conservation and action. That was really what launched me into the career I have today as a full-time artist, where I create art to hopefully inspire people to feel deeper personal connections to the marine environment and to care and act to protect it.

Why did you choose to create large-scale sculptures?

I think most ceramic artists will find that they have a comfort zone that’s about this size (motioning something small). Everybody wants to make work that’s relatively small, and I definitely started that way also, just to get the basics. Then, I was honestly really inspired by coral reefs. Corals are sculptures, and that’s something I realized when I first went scuba-diving. I found that everything looked very sculptural to me and these animals that are corals are colonial, and by building these giant colonies and communities of different species they are sculpting their environment. That inspired me to create bigger and more complex installations.

I took half of my course work at the Rhode Island School of Design when I was doing my master’s, and it was really during a critique there that I felt compelled to create something really massive and something kind of a little bit intimidating, just in order to get people’s attention. I felt like the problems are so big, like climate change is spelling doom for coral reefs, and I want people to pay attention, so I felt like doing something really gigantic would help do that.

Your choice of materials seems to be conscious and deliberate. You state on your website that you use ceramic because “the chemical makeup of your work parallels that of a natural reef,” and also because both your sculptures and living corals “share a sense of fragility that compels observers to look but not touch.” Can you tell us more about that?

I think ceramic is a natural material to use for portraying coral reefs because partly, the chemical makeup of ceramic, a lot of the glazes I use, incorporate calcium carbonate, which is actually the limestone material that corals precipitate when they’re building a coral reef, so chemically there is some kind of parallel there. And then, I also think it’s just really inherently sensical, I think it’s a powerful idea to think that corals are so fragile in the wild and if you touch them, they can break so easily, and that’s really similar to ceramic and porcelain. In particular, you can imagine porcelain anemone tentacles break very easily, so my work has to be handled with care, and while I make every effort to not break it and to have professionals handling my work all over the place in order to preserve it, in a way it’s sort of that performance that is trying to protect the reef that I’ve built.

Many of your pieces juxtapose a healthy-looking coral with whitened coral, and that is to highlight the issue of coral bleaching. How did you come up with this idea?

That was something I came up with during my master’s thesis at Brown. I wanted to create a masterpiece, I didn’t completely know what that meant, but I wanted to create the first installation I had ever done that was going to be enormous and grab everyone’s attention. I didn’t want people to have to read about the work to understand it. I wanted people who were somewhat informed about the issues to be able to interpret it, and so I felt like portraying that transition from healthy, colourful, vibrant, living corals to the ones that are sickened and bleached because of stress from temperature change, often due to climate change mixed with an El Niño event, I thought that was a really powerful and simple way to visualize climate change.

I’ve come think of coral reefs as just a way to visualize climate change in general. I think it relates to all of us. You don’t have to live in a tropical place where coral reefs are right in your backyard to relate to the issue. I think it’s hard to visualize something like climate change. We see so many sad images in the news of polar bears stranded on icebergs and fires burning in the West and things like that, but corals are so quiet and fragile and beautiful that I think, even though it is still a heartbreaking visual, it can be kind of an intricate, amazing thing to witness as well.

I feel lucky that I’ve seen coral bleaching in the wild, as weird as that sounds, and it was very sad to see, but coral bleaching happens relatively quickly. Not many people actually get to see corals that are in the process of doing that, of losing the symbiotic algae that live within their tissues and give them an important food source. There are these tiny algae that photosynthesize inside the coral skin and essentially when the coral becomes stressed by higher sea temperatures, these algae get evicted, they get pushed out of the coral, and the coral itself without those algae is completely white, so the coral is still alive but it’s essentially starving and it gets sick really easily. Seeing that happen is really kind of rare. Soon after that happens the corals often succumb to disease or die from starvation, so a lot of times what you see, like if you go snorkeling in Florida or something, that is a reef that’s already gone through that process and has died already and is covered in this kind of slimy green algae.

You are also involved with conservation efforts. Can you talk about your work with Mission Blue and tell us what Hope Spots are?

Dr. Sylvia Earle is this legendary oceanographer who I’ve admired for my entire career and as a teenager. She is the founder of an organization called Mission Blue, and the main point of Mission Blue is to highlight places that are particularly vital for the health of the ocean. Hope Spots are these places that a committee of scientists and experts has identified all around the world in the ocean as being particularly important to preserving the health of the ocean. It’s a way of promoting the creation and implementation and enforcement of marine protected areas by different governments all over the planet.

Lastly, why do you think people should learn and care more about life below water?

I think we’re all connected to the sea; life came from the sea. It’s amazing how much we derive, even if you live in the middle of the continent a mile above sea level, you still derive life from the sea. Oxygen and the water we drink and a lot of the food that we eat is really dependent on that, and it’s something that keeps our planet healthy, so we really need to protect that. As Sylvia Earle from Mission Blue says, “Our life support system is the ocean.”

Cover image: Courtney Mattison by Jeff Minton. Image courtesy of the artist.

Learn more about Courtney Mattison and check out her current exhibitions all over the world on her website.