On my 17th birthday in my freshman year of college, I was gifted Dawoud Bey’s Harlem, USA. It was my first time seeing his name but I was familiar with his work through online platforms like Tumblr. On Tumblr, people would upload photographs and works that resonated with them, they connected to and that they wanted to share with others. A large number of art school graduates who are Black can thank platforms like Tumblr for their education in Black arts since most institutions do not have a proper curriculum that guides creators through the history of Black artists and their works.

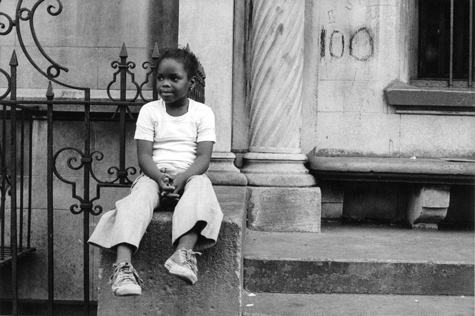

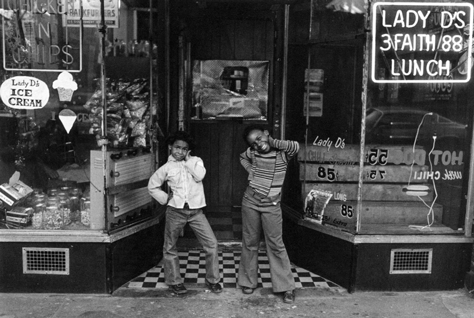

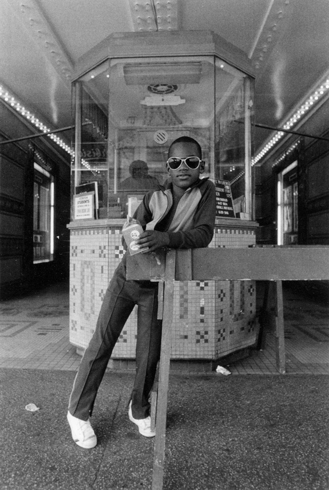

Dawoud Bey’s work keeps a chronology of Black history in America. He was born in 1952 in Queens, New York. His parents met in Harlem, and many of his aunts, uncles and family friends stayed in the area, which he returned to, to visit. His work captures the changing landscape of Harlem in the 70s, a place he continues to revisit in his work. His most recent work in Harlem is evidence of the gentrification happening and how the community continues to shape itself as their space is being forced to change over time.

Harlem, New York, is a pillar in the history of America, known most famously for the early 1920s to 1930s Harlem Renaissance, an African American cultural movement. The neighborhood of Harlem is a landmark in culture from music to literature, from real estate to art, from dance to finance. Harlem is home. Many immigrants from the African diaspora and the Puerto Rican community have also found a home and community in Harlem.

In An Essay, “Reflections on Harlem, U.S.A.” Dawoud Bey says;

“...much of what I did was not photographing, but spending time walking the streets, reacquainting myself with the neighborhood that I wanted again to become a part of… As I got to know the shopkeepers and others in the neighborhood, I became a permanent fixture at the public events taking place in the community, such as block parties, tent revival meetings, and any place people gathered. The relationship and exchanges that I had with some of these people are experiences I will never forget. It is in those relationships, and the lives of the people that these pictures recall, that the deeper meaning of these photographs can be found.” (1)

Dawoud Bey’s work ties into the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 and 11, with his work that ensures inclusive and equitable quality education, that promotes lifelong learning opportunities for all and supports sustainable communities. His need to be a part of the community and connecting to the people he featured in his work has definitely created a lifelong learning opportunity for the history of Harlem and the history of Black people in America. In 2002, he received a Guggenheim Fellowship, in 2017 a MacArthur Fellowship, and in 2019, an Infinity Award from the International Centre of Photography for recognition of his work and his contribution to both photography and history.

Dawoud Bey’s name came up twice on my path to earning a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Photography, once when I received his book as a gift from a close girlfriend and the other when my thesis professor spoke privately about her love for Dawoud Bey’s The Birmingham project.

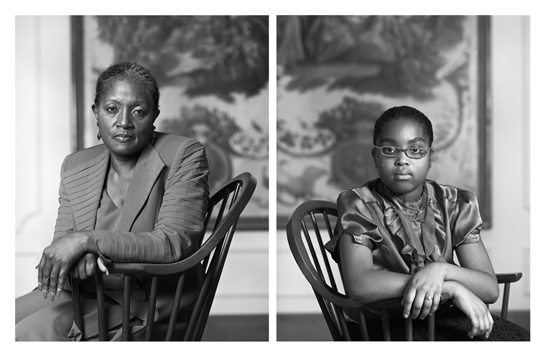

Bey’s 2012 The Birmingham project opens up space to digest the September 15th, 1963, Ku Klux Klan bombings of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, who were all 14, along with Carol Denise McNair, who was 11, were the four Black girls who were killed in the church that day. Over 22 other people were injured, including 12-year-old Sarah Collins, Addie Mae Collins' younger sister.

A photograph of her was taken in the hospital by Frank Dandridge; she had white pieces of cotton covering her eyes, her skin showed the impact and disfigurement the bomb caused, she had pieces of glass embedded into her face and lost one eye. Bey would first see this picture at a young age, and 38 years later, he would wake up when the image appeared to him in his sleep, making him head for a few months to Birmingham, Alabama, to work on this series.

Earlier in the day on September 15th, 1963, across the city, James Johnny Robinston, who was 16, and Virgil Ware, who was 13, were both murdered by two White men leaving a segregation rally. The 16th Street Baptist Church was home to Martin Luther King and many other community organizers; it was used as a meeting spot for anti-segregation rallies. Alabama at that time was considered one of the most segregated states in America. Around the time of the bombings, Black people in Alabama were pushing for racial integration and voter's rights.

For his series, Dawoud Bey photographs people from present-day Birmingham, Alabama. Some of them are the age of the people who died in September 1963 and the others are the age that they would have been if they had survived the bomb or the racially motivated acts of murder. This body of work is so haunting and succinct, it reminds the viewer of life lost, it puts the viewer face to face with the concept of life, time and death.

The diptych gives the viewer room to imagine the little girls getting ready for choir in the church's basement, their youth and their innocence robbed on a holy day. I feel as if The Birmingham Project is one of the most important contemporary photographic works I’ve seen. The subject and concept of Black life lost to racism is a conversation that we have been having for centuries and a conversation that we will continue to have if this current political, social, and economic environment persists.

Dawoud Bey: An American Project is curated by the Whitney Museum of Arts’ Elizabeth Sherman and The San Francisco Museum of Modern Arts’ Corey Keller. It’s currently on view at the Whitney until October 3rd, 2021. This show opened in November 2020 to March 2021 at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia. Both shows feature images from the Birmingham project and Harlem, USA as well as other known works by Bey.

If you are looking to see his work in the city, some photographs by Bey can be found at the AGO (Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto) until December 2021. They are located in Gallery 129, the Robert & Cheryl McEwen Gallery. The featured work is taken from his series Night Coming Tenderly, Black. In this project, Bey goes to particular locations from the Underground Railroad, the route enslaved Black people took to flee from their oppressors. He photographs these environments at night with the ambiance being a reminder that the land never forgets.

- “Reflections on Harlem, U.S.A.” Quote from Dawoud Bey Harlem, U.S.A The Art institute of Chicago. Distributed by Yale university Press. 2012. ISBN 978 0 300 18126 5