Picture this: You’re writing a letter beside the fireplace. Your quill is suspended mid-air and ink drips onto your letter. You hastily scribble out the word it bled on to. A clear image of your audience—your loved one, your friend, your boss or neighbour or news editor persists in your memory as you write. You read the text over and over, searching for the right words to convey your experience. In a way, you’re a storyteller.

Fast forward a few centuries, and you’re an avid Facebook/Twitter user where you post about your real-life experiences. You have different audiences depending on the different people in your social life. No matter which digital platform you use, you want your posts to appeal to your fragmented audiences.

The same essence of letter-writing is seen in our storytelling techniques in the digital age. We use language and formality to share stories with our followers and audiences. This essence is the human touch. And we love seeing it across art and media.

While our main medium of practice has changed, the storytelling need hasn’t. Letter-writing is not a dying practice that must be salvaged, nor is it an adversary of paper; it takes on many forms and captures the sentiments we want to share with people.

To successfully charm the modern reader, a handwritten letter must have at least one of the following: actual handwriting, scribbles, ink blots, paper creases, seals and stamps. Essentially, the “limbs” of the letter add to its authenticity and romance in today’s age.

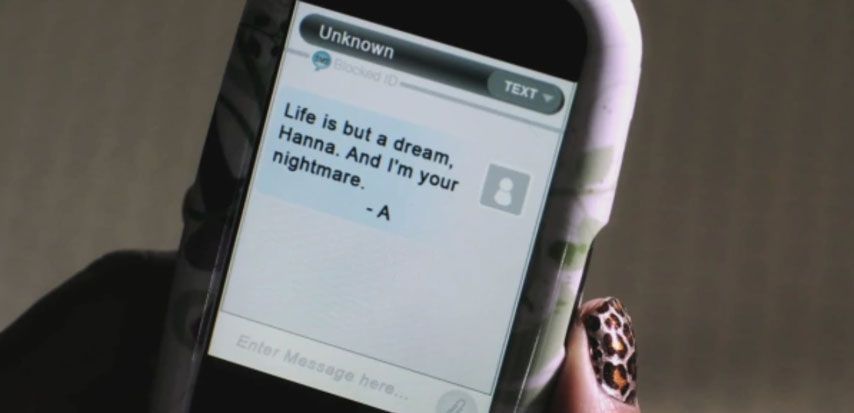

Many contemporary novelists and filmmakers have also adopted a digital medium to shape their narratives. Snippets of screenshots, emails and texts in novels or in movie scenes is a modern storytelling technique. Examples include TV shows like Pretty Little Liars, Gossip Girl and Brooklyn Nine-Nine, where the leading detective Jake Peralta and Captain Holt complement each other’s characters yet share a wholesome father-son dynamic.

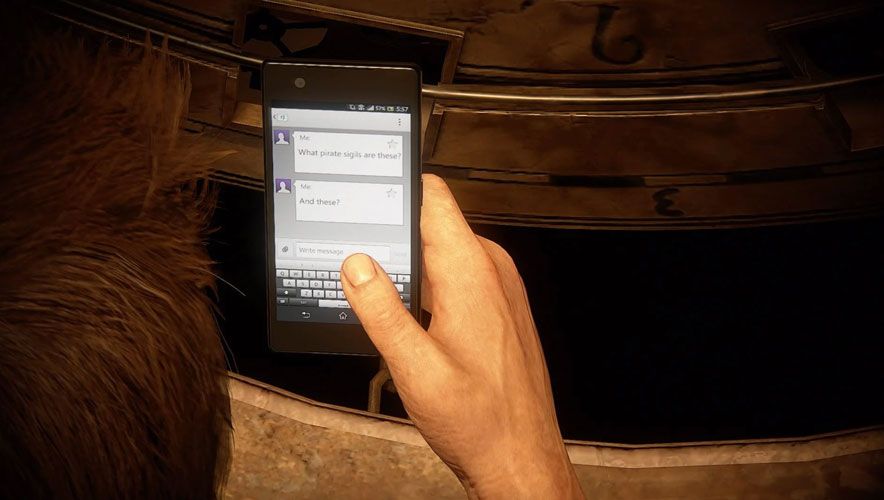

In video game franchises like Uncharted, protagonist Nathan Drake and Victor “Sully” Sullivan show their father-figure dynamic through their texting styles.

The live-action film (2022) alludes to the same dynamic when Drake writes long texts to Sully describing parts of their mission. Sully’s icon says “texting” for some moments until we see his response: “K”. This scene relates directly to young people’s humour, where parents limit their responses to their children’s texts to a few words, unlike their children. The generational “universality” of the “dad trope” in this scene was relatable for many young people in the audience and is culturally acceptable as Internet humour.

Other examples lie in the literary world, from horror stories told through text to young adult fiction. Sally Rooney’s latest book Beautiful World, Where Are You about contemporary love and human connections, include descriptive chapters with narrated texts to show how the protagonists interpret tone and voice. The author’s narrative style between texts and physical interactions almost flow into each other because the characters’ digital and physical realities converge at the same points in time.

Whether the letter is physical or digital, we want to use the right language to spice it up. We decide the levels of politeness and “relatability” and humour according to our audience. Humans suffer from the Golden Age principle—a sociological phenomenon where we tend to romanticize the “good ol’ days” as better than our contemporary age. We romanticize the language, the art forms, the inventions and the general lifestyle as superior to our current state.

No two social media platforms are identical—each comes with features unique to its purpose to help us shape our narrative the way we want. We wouldn't necessarily use informal slang acronyms or emoticons in a letter, but they do add some human touch in an email and texts. And words, whether on physical paper or email, always have a tone that is open to the reader for interpretation.

Languages are a dynamic form of human expression. It is natural that they should change, alongside the medium we use to express ourselves. From stone tablets to papyrus to the telegraph to typewriters to emails, humans have come a long way. Our use of the written form is an art in and of itself, and just like other art forms, it evolves.

In her book Because Internet (2019), linguist Gretchen McCulloch notes that “Writing is a technology (...) that [is] greatly affected by the tools available to make them: it’s easier to carve wood or stone in a straight line, but easier to swirl and loop with ink (p. 15). Linguistic complexity is unrelated to the complexity of the material culture it comes from. Language has existed with or without all kinds of technology—and the Internet is no exception” (p. 273).

As people progress with their technology, their art forms evolve alongside them. Because it evolves just like any other art form, it leaves behind a cultural heritage that we should preserve in the digital medium as well. This unconventional art form echoes the Sustainable Cities and Communities goal from the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

If we adopted the perspective of future historians now, we’d be able to explore the revolutionary period we live in through curiosity and excitement. The digital art of letter-writing isn't lost but has changed mainly in the medium and our use of narrative language in emails, texts and social media posts. So this art isn’t dead, nor do we have to “reclaim” it; it has adapted, and it ought to be appreciated as a product of our times.