Animation is one of the most versatile art forms, yet its artistry is predominantly reserved for comedy and kids content. With Japanese animation being the exception, much of the art form lacks in genre diversity, snubbing its own potential. Independent animator Don Hertzfeldt, however, is exploring this potential and pushing Western animation into new territory. Lying somewhere between philosophical and comedic, Hertzfeldt’s bizarre filmography exemplifies “less is more” as it shifts the landscape for future animation.

Hertzfeldt, who has never had a job outside creating his own films, developed acclaim early in his career, having his film school short, Billy’s Baloon (1998) played at Cannes Film Festival a year after it was created, then being nominated for an Oscar just a year later with Rejected (2000). His early work up until the early 2000s is centered around absurdist, black humor, commenting on topics such as consumerism and commercial art as seen in Rejected. His films since have taken an introspective turn, examining mature and expansive topics through his unique animation featuring stick people.

The Meaning of Life (2005) is Hertzfeldt’s first venture into the existential and solidified his distinctive style. The twelve-minute short film showcases human evolution far past Homo Sapiens set against the backdrop of dramatic classical music. In contrasting the simplest possible visual depiction of humanity—stick figures—with the vastness of time and the cosmos, The Meaning of Life distinguishes itself from the countless cinematic portraits of evolution through the perspective gained from Hertzfeldt’s minimalism and sense of humor.

The Meaning Of Life, along with the majority of Hertzfeldt’s animations are the result of years of dedicated work to hand-drawing his thousands of frames. Although working as the sole creator for his films is a painstaking process, being an independent filmmaker allows Hertzfeldt an autonomous freedom rarely found in the film industry. Paired with an aversion to experimental animation among most animation and distribution companies, Hertzfeldt’s freedom of self-employment means he has never had to compromise his alternative approach to animation, and the result is unparalleled.

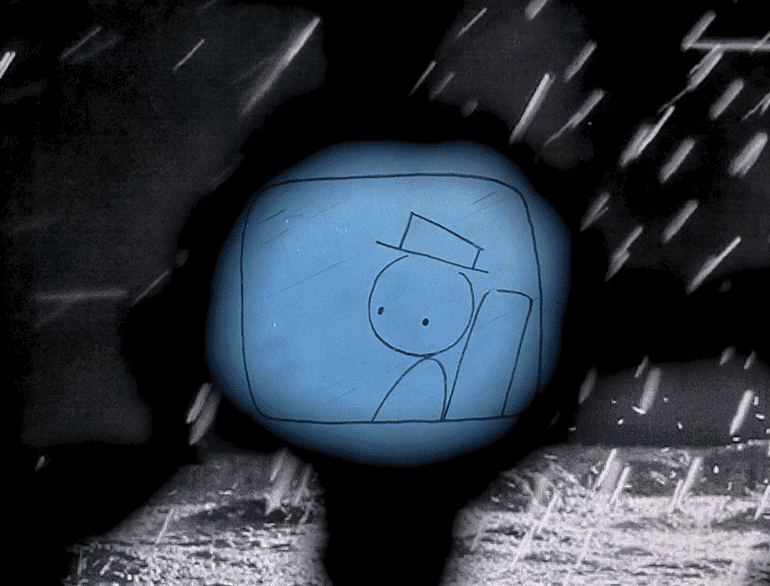

Hertzfeldt’s only feature-length film, It’s Such A Beautiful Day (2012) is Hertzfeldt at his most ambitious. The film follows an ordinary man, Bill, through his daily life and mundane tasks as his mind slowly deteriorates from an unnamed neurological illness. Bill’s life is seen through a mix of traditional hand-drawn animation, trick photography, and experimental optical effects tied with often disruptive sounds and classical music. The overlapped sounds and images are strung together by a detached narrative done by Hertzfeldt himself, detailing Bill’s every thought. Here, Hertzfeldt represents reality enough so that it is discernible, yet breaks it down to its simplest elements: a bus window is just a square, a table is just a line, a face is just a circle. Though reality is nothing but lines and shapes, the emotional draw is as powerful as ever, or more so than any other film, owing to Hertzfeldt’s use of alternative methods of storytelling. It’s Such A Beautiful Day is entirely impressionistic in its execution through its use of experimental techniques to express the indescribable emotions and internal happenings of its protagonist.

In balancing humor with philosophy and complex narratives with simplistic animation, Hertzfeldt has created films that can be viewed as anything from absurdist comedies to bleak portraits of the human condition. This range gives way for viewers to experience his films on their own terms, whether in search of a light-hearted comedy or an insightful tragedy. The minimalist animation style assists in this subjective viewing experience by allowing audiences to fill in the blanks. The abstract landscapes provide only a foundation of a setting and the simplistic character design only allows for a limited expression of emotions, inviting viewers to interpret the film’s tone.

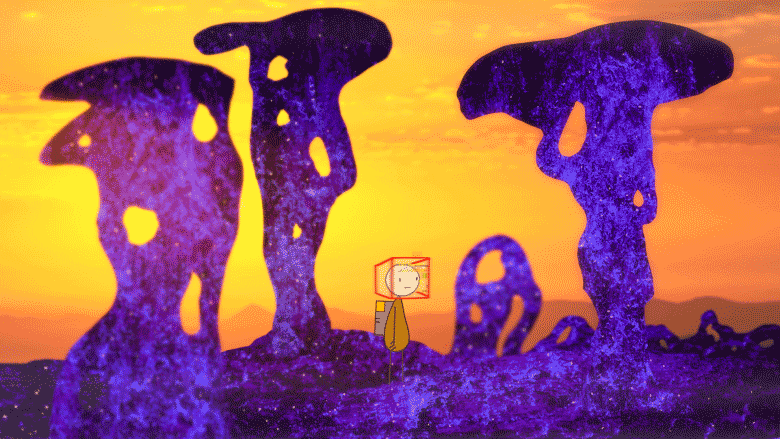

Hertzfeldt’s most recent project, World Of Tomorrow (2015-2020), an episodic three-part series, is the filmmaker’s first use of digital animation. The series dives deeper into Hertzfeldt’s universe with a story set in a dystopian future, exploring the philosophical implications of cloning as means of extending one’s life. The series shows Hertzfeldt’s animation at its most complex, each episode being more beautifully rendered than the last with vast and colourful surreal landscapes, yet the simplistic design is still present. Hertzfeldt’s minimalistic animation style provides a newfound clarity to the complexities of humanity’s existential inquiries. Through visual worldbuilding that doesn’t attempt to mimic, but merely represents the real world, the film’s existential themes are given a chance to be viewed with a level of separation, allowing the audience to gain perspective on intensely human and oftentimes tragic narratives.

In a time overwhelmed by existential dread triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, Hertzfeldt’s work gives a much-needed perspective and a rare optimism to today’s concerns by speaking through his characters, such as Emily from World of Tomorrow, to confront his audience with truth in the midst of absurdity.

“Do not lose time on daily trivialities. Do not dwell on petty detail. For all of these things melt away and drift apart within the obscure traffic of time. Live well and live broadly. You are alive and living now. Now is the envy of all of the dead." - Don Hertzfeldt