A visit to the Remington Contemporary Art Gallery (RCAG) in Downtown Markham may include a curious encounter with an unlikely individual. Always on watch, the RCAG’s most dedicated member of the security service stands steadfast and faithful at his post, day and night, the serious yet approachable expression on his face bringing reassurance and comfort to those who pass him. This unnamed man is, in fact, a polyresin sculpture created by hyperrealist artist Marc Sijan, and with its slight tilt of the head, distant yet inward-facing contemplative stare, and painstakingly applied layers of oil paint that seem to bring the surface of the sculpture to life, the RCAG security guard is undoubtedly a sight to behold.

The gallery’s most whimsical staff member is a recent addition to a series of security guard sculptures initially inspired by the artist’s father. Sijan has exhibited in dozens of galleries worldwide, but in his home-base of Milwaukee, his most famous local work sits at the NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks Training Center. Bearing the playful moniker Art, a sculpture of a seated security guard rests near the Center’s entrance and has caused much confusion for people who believe Art to be a real person. According to multiple anecdotes, Michael Jordan once became irritated on a visit to the Bucks headquarters when Art ignored a question from the legendary sports figure. Several others have recounted similar experiences of approaching Art and the RCAG’s security guard, only to find out to their wonder and surprise that they were looking at an astonishingly realistic sculpture and not a human being. Already a beloved staple of the gallery and a must-see attraction for Markham visitors and locals alike, no doubt the RCAG’s security guard will cause much of the same lighthearted misunderstandings for years to come.

An Interview with Marc Sijan

Though his prolific output of work may be mostly interactive in presentation and social in meaning, the subdued and pleasantly earnest Sijan rarely talks about his own work. Notoriously private, Sijan prefers to speak through his art, in which he strives to apprehend a person’s humanity through their physical flaws, their posture, and their unmoving demeanour. However impressive his uncannily realized sculptures may be, it is no doubt the affection with which he produces them and the sense of presence imparted into his figures that resonates so thoroughly with the viewer. Arts Help writer Laura Thipphawong recently spoke with Marc Sijan about his career, his inspiration, and his goals for the future of his work.

How long have you been working as an artist, and how would you describe your work?

I’ve been an artist, probably all my life. As a child, I remember playing with clay and Playdough, making sculptures, and they certainly weren’t realistic, but the human form… I think the human form is the oldest subject matter known to mankind, all the way back to the caveman; everybody’s been working with the figure. So how long? All my life, and now I’m in my 70s. My work is life-size figurative sculpture. I deal with realism, they call it hyperrealism, ultra-realism, all meaning the same thing.

What was it that first made you want to steer your art career in the direction of hyperrealism and of portraying the human figure?

I like the idea of perfection and the exactness of the technique involved in hyperrealism, right down to the fingerprints and the moles and the freckles and the veins; that’s perfection. So why did I go into hyperrealism? It evolved over a long period, and it certainly didn’t start that way. As it does with many artists, the process evolves over a period of time. And I didn’t do it to try to fool somebody into thinking that they were real people, the realism came about as I was dealing more with the sculptures’ internalized energy.

Assuming that the human body is still inspiring to you, can you tell me what it is that keeps your focus on human anatomy?

I’ve always been intrigued by people: people on the street, everyday man, the common man, and I try to let the energy do the speaking, and I like the attention to detail it takes to make a hyperreal sculpture. The challenge of capturing that energy keeps me inspired.

Your security guard series is famous for being so lifelike that people stop to ask them questions. This type of thing wouldn’t happen if they were displayed in a traditional museum arrangement, say, on a pedestal. Is there something about integrating the sculptures into a real-life setting that you find more compelling?

You could put it up on a pedestal, you could have a Michelangelo standing up on a pedestal, and everybody looking at that marble pedestal would know instantly that it’s a sculpture because most people wouldn’t stand on top of a marble block or wood base because usually that is reserved for presenting something very special. They may have a showcase where they display their work that way, there are different ways of doing that. But I want to strip that away and have the work in a natural setting, where the area around it makes it more believable and more comfortable when trying to present the idea of the human form.

I’ve read that the concept of art is everything to you. One piece that stands out to me as very conceptual is Birth. Can you explain the concept there, and is there a piece that you find to be particularly meaningful to you?

The subject of Birth, a man emerging from a wooden crate, is similar to something I can remember doing as a child. I can remember going into cardboard boxes from the refrigerator in the backyard and hiding in there. I would put little windows in it, cut little windows from the side, and there was a security and comfort level. Like the womb, the safety of the whole thing, that’s part of what Birth was all about. It’s called Birth, the man is naked, and he’s emerging from this box, this shipping crate with the pink shredding, the shipping filler, and this man is about to be shipped off to who knows where, but he’s very comfortable in his own skin, as they say. We don’t know where the crate is going to go, that’s up to the viewer. I don’t usually explain what I do with art because I want the viewer to do the thinking, to think about what they’re looking at. There may be ten people looking at a sculpture, and you’ll have ten different interpretations of what they see. Their feedback is different than that of the person next to them. They may see it differently than what the artist had in mind. I don’t want to fill in the blanks; I want them to scratch their head and discover why the artist is doing what they’re doing and see what’s going on within the sculpture and the total presentation.

A sculpture would not be interesting to anyone if there wasn’t a sense of soul in it. I imagine that seeing them increasingly develop must have some sort of emotional effect. Is there an exchange or an imparting of yourself in the process? How do you breathe life into your sculptures, so to speak?

I can remember one time working when I was very young at this process, maybe I was in my twenties - it was one of the early pieces, a pretty significant piece, and I was by myself in the studio working hard. I am a workaholic, and it was a Friday night, and it sounds really goofy, really silly, but based on some mythology, I decided to do it, go over and put my mouth over the sculpture and breath air into the sculpture. I’ve never admitted that. Hmmm… interesting.

How do you relate to your work as you’re making it? What makes them believable to you?

I’m an observer in people all the time, probably more than most people. I’m looking at people, I’m looking at what they’re doing, maybe what they’re wearing, their body language, and always my sculptures are at rest, they are between action in a moment of pause. It would not look realistic if I had someone try to jump over a candlestick. Jumping into the air would not be believable. I would have to suspend them from wires or something. The sculptures being at rest makes them more believable, I think.

Where do you find your inspiration for new work, and are you working on anything now?

Most of the time, I spend is not with my fingers on the materials, which are polyester resin and artist’s oil paints. There are two parts of the process: the sculpting part and the body cast, and the painting part is the second half of it, but most of the time I’m working on art, I’m thinking about it. If I’m at a party (laughs) before COVID, I mean, or if maybe I’m at church or out walking, I will think of things, and I will write them down. I’ll jot down some notes, and sometimes at the most obscure time, I’ll see somebody somewhere, and I’ll go, wow, that’s really convincing, maybe that would be a good pose, maybe I should think about sculpting something like that. So, I sometimes look on the internet for images, but mostly it’s things from real life. I’ll be driving in the car, and I’ll see somebody, maybe someone sitting on the street and I’ll look and I’m going at a fast speed so I’ll have to go around the block and get a look at this guy again, to see all the little nuances about him that would make him convincing. I’m inspired by the common man, nothing special, someone you would pass up on the street, and you wouldn’t think about, that is my subject matter.

What would you like to do or see in the future, and what is it that you want your work to express?

Whatever’s worthy. I used to work faster, I used to work on a lot of pieces at one time. I used to kind of crank them out, as you’d say. Now I spend a lot of time not with my fingers on the sculpture but contemplating what is worthy, maybe something that no one has done before, something that I’ve never done before. What is something that will surpass anything I’ve ever done before? And only if it’s worthy, and only if it’s of real consequence, will I pursue it, and therefore I don’t even create new sculptures that often. I’m very selective these days, and it has to catch me just right, when I force it, it doesn’t come, it sometimes works best when I just let it happen or maybe some image I’ve seen somewhere just comes into me. I used to go to the library with my friends, and they’d be studying or reading, and I’d be looking at pictures, visuals, things that would lead to something else for me. And this is very difficult because there have been millions and millions of interpretations of the human anatomy, so I’m looking for something that comes from me, and only if that happens does it have a really strong message that is powerful enough. I want it to be something that’s remembered by people after they’ve seen it. I want somebody to see something and then see it later that night in their mind, see that image that they can’t get out of their head. That’s the kind of impression I want to leave.

Biography

Marc Sijan is a self-described lifelong artist. Born in Serbia in 1946 and based in Milwaukee, Sijan has been working in the practice of hyperrealist sculpture media for decades after studying art theory at the University of Wisconsin, where he achieved his Bachelor of Arts Degree and his Master of Science Degree in Art with a major in sculpture and ceramics and a focus on the human anatomy. It was then that Sijan made the personal decision to devote his life to self-expression through visual media, a decision he felt was his most natural path and one that has allowed him to continuously create work that showcases his view of the world to this day.

Though he studied in the traditional sculpture methods and has been directly inspired by Michelangelo’s classic depictions of the human form, Sijan’s work lies in the definitively postmodern spectrum of the simulacrum, art that makes the viewer question the meaning of art by representing reality to near perfection. Among the trailblazers of the hyperreal movement in mid-century America, Sijan adapted his work to test the boundaries of visual representation; it was through this exploration that Sijan became a protégé of hyperrealism pioneer Duane Hanson (1925 -1996) in the 1970s, a time sometimes referred to as the Golden Age of Hyperrealism.

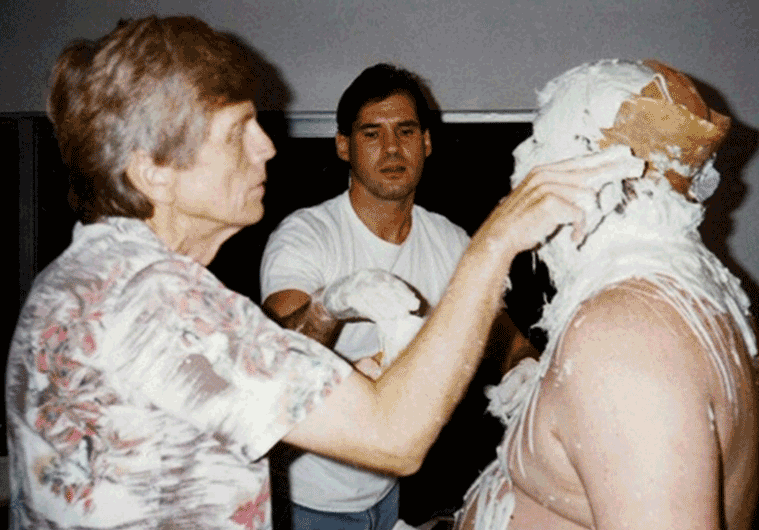

Together, Hanson and Sijan developed ground-breaking techniques of sculpting plaster mould interiors using magnifying glasses to capture the most minute of details. Now considered to be Hanson’s successor and the top hyperrealist sculptor globally, Sijan continues his practice of creating soulful representations of real people, most often those who are working-class and unidentified, making his work realist in both form and in concept.

Arts Help is proudly supported by The Remington Group