Have you tried visiting an eat-all-you-can buffet and wondered what happens to all of the uneaten food after closing hours?

It is no surprise that the food in these establishments are discarded contributing to the 1.3 billion tons of edible food wasted annually by the world. Yet with all of these amounts of food in circulation, the United Nations recorded that approximately 690 million people or 8.9 percent of the world population is hungry.

The problem is not the lack of food production but the accessibility to it, coupled with income inequality and economic instability. To better understand these troubling statistics, take a look at Filipino artist Elmer Borlongan’s works.

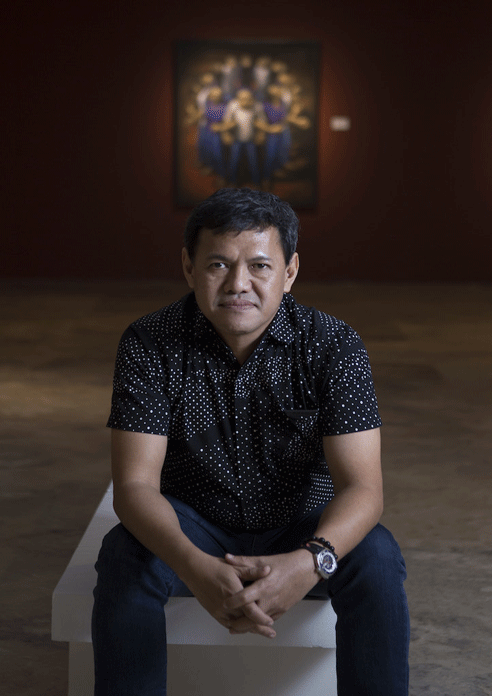

Elmer Borlongan grew up in Mandaluyong. His experience living in both urban and rural areas of the Philippines allowed him to have a first-hand encounter on the various faces of food insecurity. His works represents the Sustainable Development Goals on No Poverty, Zero Hunger, and Reduced Inequalities.

“His obsession lies not in depicting the ordinary, but in highlighting the visually disturbing images of an imperfect world,” writes AskART.

Borlongan had formal training in painting since he was 11 under the guidance of Fernando Sena. Later on, he majored in painting at the University of the Philippines.

Hating Kapatid (Brother’s Share) depicts two scrawny identical teens laying down in a single-person bench. Both of them are crouched perpendicular to each other, trying their best not to fall down.

In colloquial terms, Hating Kapatid means splitting things equally like how siblings share. Although the value of resilience is admirable, it presents a bigger issue on poverty.

Exploring the slums of urban Manila, he was made aware of the hardships and challenges faced by the Filipinos. He has seen poverty knock door to door and steal food from hungry plates and left the homeless on the dark cold streets.

The Happiest Place on Earth shows a person eating french fries.

For context, the french fries in this picture came from a popular Filipino fast-food chain. Rich or poor, Filipinos can recognize this emblem. For some, this simple food feels like a luxury so they have to save money just to buy it. Looking at the bigger picture, fast food chains and restaurants are key contributors in the global food waste production. Food services comprise 26 percent of the total food waste generated per year.

This piece begs the question— with all of the problems fast food industries contribute, is it still the happiest place on earth?

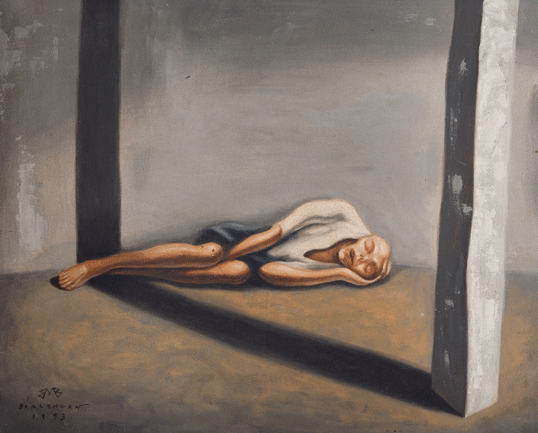

Poverty has various manifestations in different areas. A depiction of it can be clearly seen in Kubli. A laying male in a fetus position can be seen in a poorly lit room. His body is pressed in the cold concrete floors while he tries to retain the heat. The elongated figure and colour palette are reminiscent of Borlongan’s style.

Unfortunately, this scene is not foreign to most. Because of food scarcity, some impoverished children simply sleep without eating, unsure of their next meal. Around 381 million people in Asia are hungry or exposed to food insecurity. Borlongan documents these intricacies to avoid risking the erasure of their lived realities.

There has always been a fine line between romanticizing the lives of the poor and providing the marginalized an opportunity to be seen. Throughout his works, Borlongan does an intricate job of attesting to the authentic struggles of the marginalized in hopes of amplifying their calls.

For more information about Elmer Borlongan’s works, click here. If interested about initiatives and helping to eradicate world hunger, click here for a list of resources.