In 2015, the director of Lee Mullican’s estate, Ryan Good, found a series of bold, surrealist paintings among the late artist’s works. The sketches were markedly different from Mullican’s known work – colourful, striking - and signed with the initials “LH.” Good brought these sketches to Mullican’s widow, the then 94-year-old Luchita Mullican, to ask who the mysterious LH was. She lit up and replied, “That’s me!”

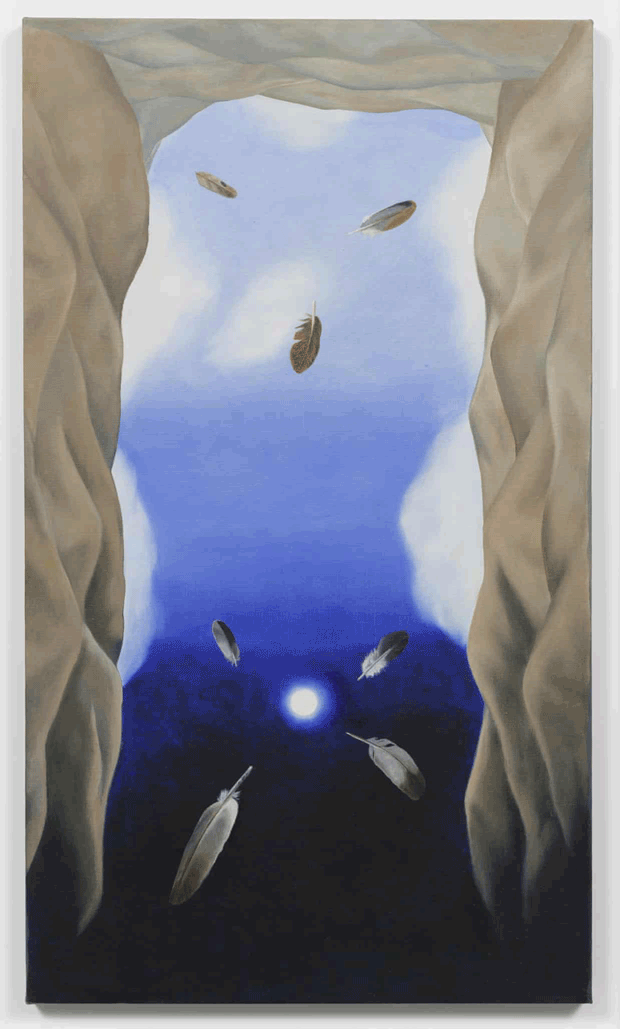

Impressed by her work, which combined surrealist forms with pre-Colombian reliefs, Good showed her pieces to Chris Wiley, who worked on Mullican’s catalogue raisonné. Wiley then showed the paintings to Paul Soto, the founder of the Park View art gallery. Soto showed equal enthusiasm, and the team rejoiced in the discovery. After a long, lucrative career that was hidden from public view, Hurtado finally received critical acclaim. She held several exhibitions from 2017 to 2019, published a book, and was named on Time 100’s list of Most Influential People. Before her death on August 13th, 2020, the 99-year-old visited her studio every day. There, she continued to paint beautiful works of abstractionism, weaving the old and the new with tribal motifs and prehistoric paintings.

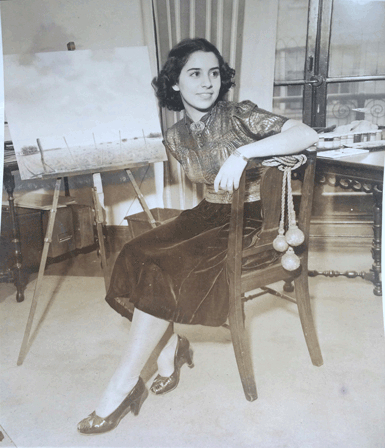

While Hurtado’s career spanned eight decades, much of it was spent in obscurity. Hurtado carefully guarded her paintings, working only at night. “I always felt shy of it,” She said in an interview with the New York Times. “I didn’t feel comfortable with people looking at my work. There was a time when women really didn’t show their work.”

As she supported her husband’s career, Hurtado painted in secret. Family and children came first for Hurtado, but, according to The Guardian, “the constraints of marriage, motherhood and the emotional and reproductive labour of the artist’s wife never stopped her [from] working.” Hurtado painted at night, in a cramped space where she could explore the boundaries between real life and surrealism. Her series of self-portraits, all untitled, use strong shapes and bold colours to create vibrant paintings. In her 1969 piece, Hurtado’s body is on full display: belly and breasts a bold shade of yellow, the Navajo rug beneath her alternating shades of red and black. A stream of light cuts the painting in half; a basket lies at her feet.

Her work was largely inspired by her life and encounters with indigenous cultures. Born on November 28th, 1920 to Teolinda and Pedro Hurtado, Luchita Hurtado spent most of her childhood in Maiquetía, Venezuela. When she was eight, Hurtado and her mother moved to New York; her father stayed in Venezuela. She never saw him again.

At fourteen, Hurtado enrolled in Washington Irving High School, where she studied art. The headstrong teen kept it a secret from her mother: “I never told my mother that I was taking art — she thought I was taking dress-making.” At 18, she married Chilean journalist Daniel del Solar, who was twice her age. She plunged headfirst into political turmoil in the Dominican Republic, and later, the New York art scene. She befriended Ailes Gilmour, the pioneer of American Modern Dance and half-sister of Isamu Noguchi. Through her connections, she met her future husband, Wolfgang Paalen.

In the 1940’s, Hurtado and Paalen moved to Mexico. Here, she befriended surrealist Rufino Tamayo and painter Marcel Duchamp. In 1947, she became Man Ray’s muse and visited Frida Kahlo’s hospital bedroom. When her son passed away from polio, she divorced Paalen and moved to California, where she remained for the rest of her life. In California, she reconnected with an old friend named Lee Mullican. The two married and would remain together until Mullican’s death in 1998. Between her adventures, she continued to paint. At the urging of artists Joyce Kozloff and Judy Chicago, she exhibited throughout the 70’s and 80’s. The Guerilla Girls asked her to join them, but Hurtado declined. Adrian Searle, from The Guardian, sums up Hurtado’s decision: “…she never was a joiner, I think.”

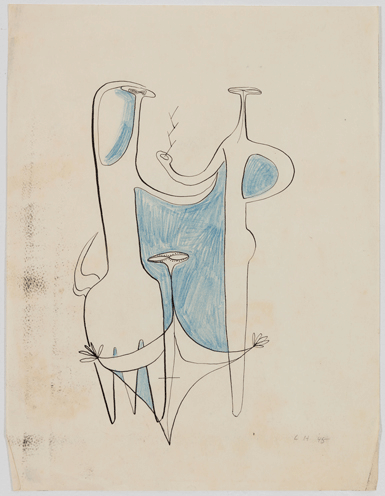

Before Hurtado’s death on August 13th, she was featured in several exhibitions throughout California. Throughout her life, she “maintained a rigorous commitment to experimentation” which is reflected in her work. Throughout the 40’s and 50’s, she focused on abstract forms, landscapes, totems, and patterns. Her paintings in the 60’s and 70’s shifted to figurative representations. Politics and a love of nature were common themes throughout her life, and are clearly reflected in Hurtado’s most recent work, “Together Forever.” It depicts three intertwined figures, who stand together against racial inequality. According to a press release: "'Together Forever' is a slogan of our time that confronts racial inequality, environmental advocacy, and united survival during a global pandemic, all in just two words."

Hurtado leaves behind a rich legacy, one that espouses equality and respects the natural world. Her late entry into the art scene makes her an anomaly: one whose legacy will be debated for years to come. While the world tangles with Hurtado’s message and how it will affect future generations, there is, at least, one lesson to be learned – it’s never too late to do what you love.