There is much to explore regarding the subject of duality, a theme that never seems to lose its luster. Though René Descartes is most often associated with dualism in terms of the metaphysical, to me the concept is best expressed by the Existentialists. In all their dark, brooding, and unapologetically gothic iterations, my favorite interpretations of the subject can be found in Robert Louis Stephenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club, and Carl Jung’s notions of the shadow. Honorable mentions go to Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Double, J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, E. T. A. Hoffman’s The Devil’s Elixir, and Bret Easton Ellis’s Glamorama. Something about the notion of a dark side in combat with one's better (or more normative) self lingers deeply with me – unlike the hero vs villain journey, revelation one’s own dark side is a universal story arch. The dark side is not always presented in the form of an evil or malevolent counterpart; sometimes, the dark side is the need for danger, or the call to the unknown. The Romantics called this kind of darkness the sublime: the terrifying and extremely attractive qualities of uncharted territory. The Romantic sublime is a prime example of duality, since it requires the internal to merge with the external – for the Romantics, singular states of emotional reckoning are found in the external universe of nature. I find this kind of duality at my core. It’s not as simple as thrill-seeking, and there’s more to being an “adrenaline junkie” than one may see on the surface. The duality of seeking both safety and danger comes from somewhere that may never be fully realized or explained.

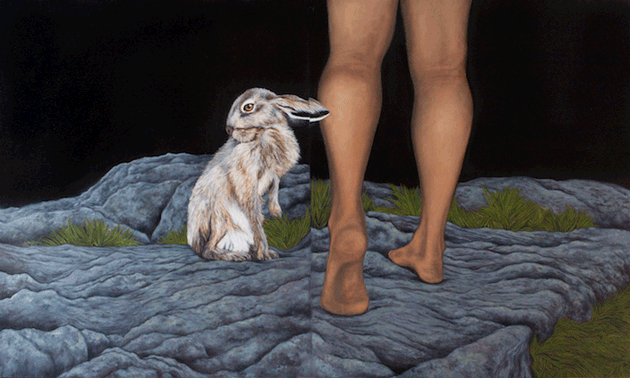

For me, this duality is best channeled in rugged outdoor experiences. I would not by any means call myself a mountaineer, a climber, or add hardcore to any such descriptive title. With respect to the people who devote their lives almost entirely to those endeavors, I would instead label myself someone who likes to climb, likes to hike, likes to venture into the mountains. In fact, I do my best to not give in to the little voice deep within that urges me to abandon civilization and live in the woods or fully devote myself to trail blazing or peak-bagging as a genuine dirtbag life-styler. Not that it would be wrong to do so, but in a personal capacity, I know that if I gave in to those urges, there would be no coming back. In deference to this notion of outlying and reclusiveness, a climber friend of mine bestowed me with the honour of my trail name, Mountain Witch, the thought of finding me lording over some mountain range in some remote fairy-tale-like cabin particularly fitting. Incidentally, a trail name is a pseudonym that thru-hikers or other outdoorsy people are given by their peers. As tempting as it is to become a full-time Mountain Witch, there is a push-pull dynamic that I feel the need to constantly mediate, and a balance that needs to be maintained. The expression of this existential dilemma is where the art comes into play.

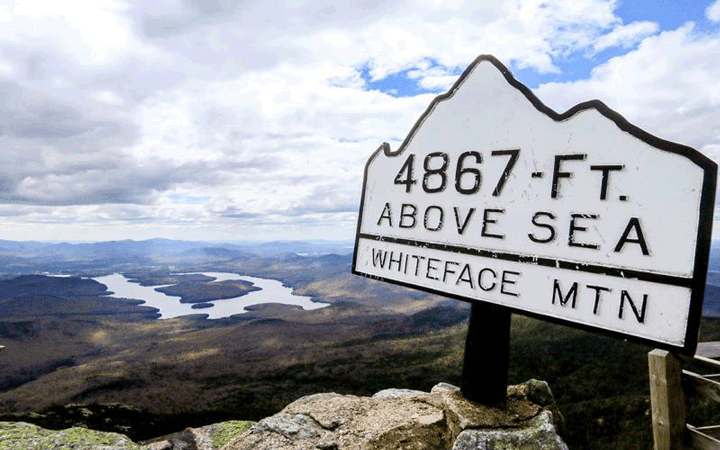

My art has almost always been about the tenuous balance and the harmony between two opposing forces. A favorite subject of mine and the topic of much of my research has been the attraction to the grotesque and the psychology of horror in fine art and media. For the last few years, this research has been focused on the interplay between danger and safety, and how those driving forces are expressed. For me, like many of my friends of the outdoor persuasion, the notion of the Romantic wilderness feeds the drive that compels us to seek out both physical and mental limits as well as precarious situations. To cite an overused but nonetheless ideal quote from explorer John Muir, “The mountains are calling, and I must go.” There is something pure and cleansing about being dirty, sore, tired, and even scared in a remote natural space. There is something fair and equalizing about it, something powerfully humbling and simultaneously empowering about trudging up a mountain, so much so that many women’s groups and trauma survivor programs utilize hiking as a therapeutic tool for healing. Being alone in the woods brings a sense of presence and of being tethered to this world in a way that can’t fully be explained or understood, and of my most recent exhibition, more than half of the paintings were inspired by intense experiences I’ve had alone in the wilderness. One such painting, Translucent Creatures on the Ocean Floor, was inspired by one of the most surreal experiences in nature that I’ve ever had and will likely never encounter. This painting documents, in an off-center way, the time I was caught in a thunderstorm alone at the top of a mountain in the Adirondacks. Whiteface Mountain, to be specific: 4867 feet in elevation, the fifth highest mountain in New York State and an 8.3-mile hike to the top starting south of Lake Placid.

Having taught several backcountry safety clinics, I should have known better than to end up in this situation. I had started a little late in the day, after my transportation was re-routed, leaving me to start close to noon on a day when the afternoon temperature was set for 38 degrees and one hundred percent humidity – but the main issue was the forecasting of a 40 percent chance of thunderstorm in the late afternoon. In my characteristically cavalier fashion, I decided that 40 percent was reasonable, and that the heat didn’t bother me, but after the first four hours in the deep woods I began to feel the effects of dehydration and heat exhaustion. Further adding to the sensation of otherworldliness was the rapid elevation gain, an average of one thousand feet per mile for the last three miles. There were several moments during the last stretch before the false summit when I remember wanting to scream or somehow give up. Turning back wasn’t an option simply because it would have been taken longer to recover that ground, and my pick-up transportation was arranged at the other side of the mountain. The relentless climb to the top became exhilarating, however, as I finally started to recognize that the treetops were getting lower and lower, and blue sky patches became visible through the cover. I had already consumed all my water and was still parched, dizzy, and nauseated from the heat, and bruised from crawling my way up the granite boulders, but I felt an unmatched sense of joy upon breaking tree-cover and looking out onto Lake Placid, all the way back from where I started. This sense of joy was, of course, short-lived.

Only a few minutes after reaching the false summit, breathing the wide-open air and feeling a cool breeze on my skin, I saw the dark clouds rolling in from the west. I remember being transfixed, knowing that I should start moving fast, but feeling like I couldn’t look away from this beautiful display that I had never seen so closely. Amid the crystalline expanse of blue sky and white clouds, a mass of darkness about the size of a car started to swirl not too far from where I stood. It seemed to pulse, and wispy tendrils like little grey tentacles started to reach out as the mass grew bigger. Then all at once I knew I had to move. As I urgently began climbing the exposed blocks of granite in the final half-mile before the summit, the entire atmosphere changed to a soupy fog, and water started pouring in all directions. Winds howled, rain hammered down, and flashes of light beamed all around me, but all I could see was the space under my feet as I tried not to fall off the boulders.

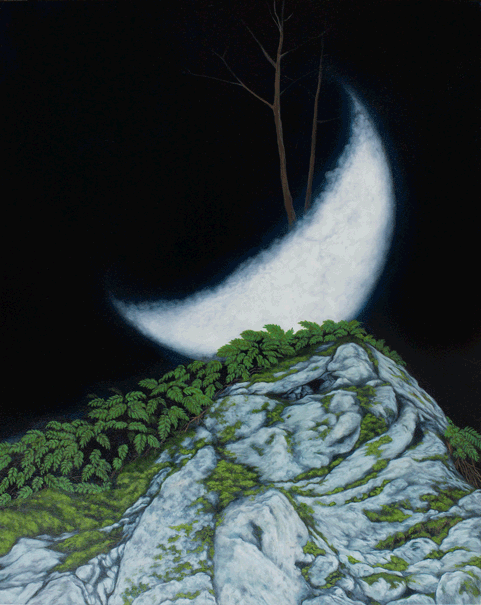

Finally reaching the summit and being alone inside a thunderstorm on top of a mountain felt mythical, and completely singular. Reflecting on the experience later got me thinking about the patterns of the world, and the chaos of time and place. The title of the painting, Translucent Creatures on the Ocean Floor refers to the fractal nature of space and our understanding of where things should be in the universe. From the moon in the sky to ocean life in the deep regions of Earth, everything seemed unified and self-similar. In the span of hours, I had moved from the hot, primordial, and insular dark woods to a chaotic and fully exposed eruption in the sky. The moon on the crag in the painting represents the collection of converging oppositional forces, or the placing of two things together that might not naturally share the same space.

Loving nature while trying my best to nurture a healthy respect for its danger has been a significant part of my life, and an immense source of artistic inspiration. The analogy of nature and its beautiful treacherousness to all aspects of life and the human condition is endless, and as I continue to explore what nature means to me, I hope to always have room to grow in my expression of it.