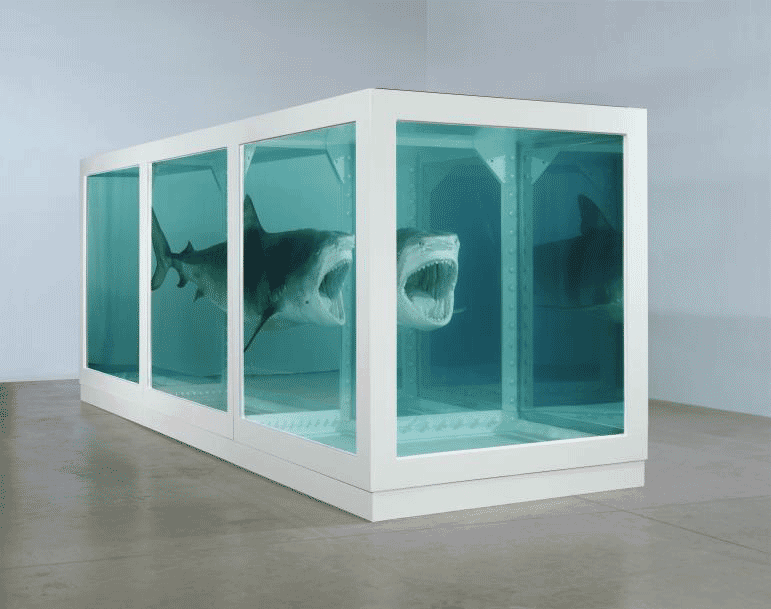

The image of a real shark suspended in formaldehyde and caged by an uncharacteristic metal and glass tank has defined modern British art and pop culture from the 1990s onwards. Jaws wide open, the shark, though dead, seems frozen in time, allowing museum-goers to inspect close-up, and first hand, what has come to be known as a symbol of deathly fear. Though the very ability to capture fear itself and put it on display in museums, confirms the absurdity of the animal’s symbolic association, confronting one’s fear without the danger of harm is a rare opportunity, yet one that Damien Hirst does constantly. Damien Hirst has been confronting viewers with death, an intrinsically human fear since he first began creating art, pushing the use of natural materials in art to new, ethically obscure territories in the process.

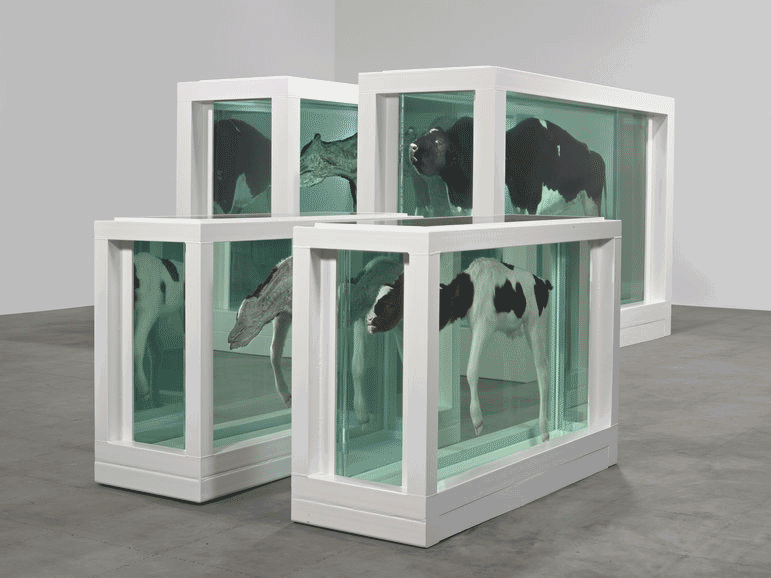

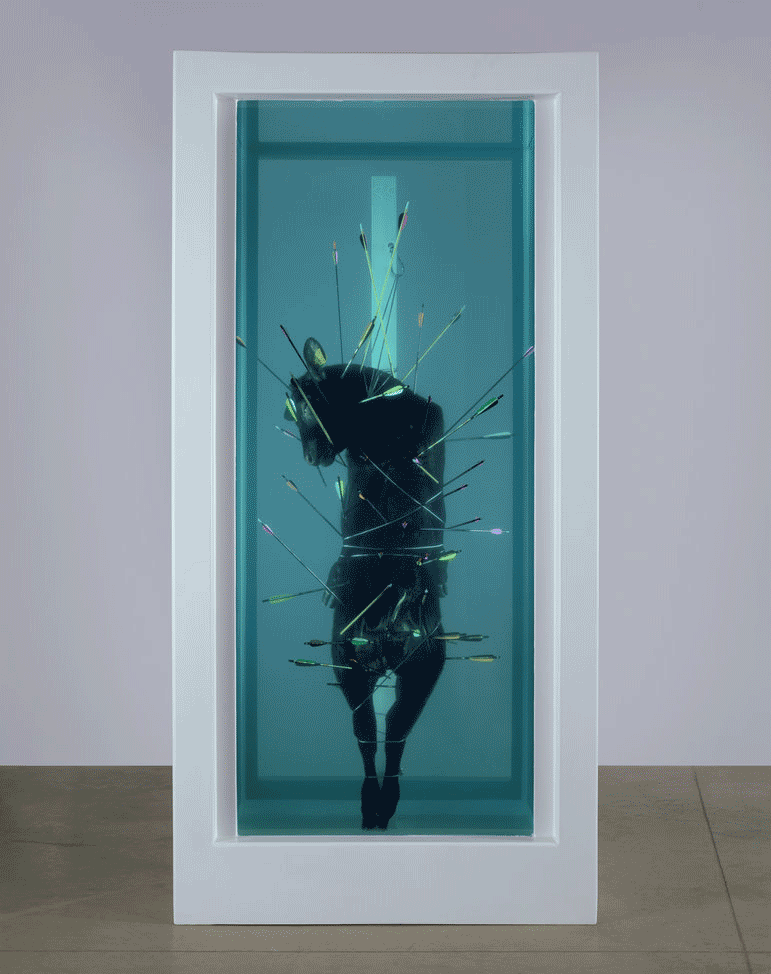

Though the theme of mortality present in the overwhelming majority of his works is nothing new, his materials are what catapulted the artist into fame. Sharks, cows, butterflies, fish, flies, and countless more creatures sit among the artists’ paint and canvases. As seen in multiple works such as his pop art inspired Til’ Death Do Us Part (2012), Hirst doesn’t need the bodies of dead animals to express his fixation on death, and although his artistic intentions are speculated to be for shock-value, the use of once-living creatures in his art has created artworks on the topic of mortality more effectively than perhaps any before it. The animals or insects and how they are presented bring a confrontational perspective from which to look at death: face to face, an irreplicable experience.

Damien Hirst didn’t invent the use of animals in art, in fact, Hirst's use of animals could be considered ethical in comparison to others. However, Hirst is perhaps the only artist to reach the status of multi-millionaire through his use of real animals in art, inevitably finding himself at the center of criticism from animal rights activists outraged with the killing of animals and insects for artistic means. Though some creatures died before Hirst claimed them for his work, many have died because of it, totaling an estimated 913,450 creatures. Hirst is no stranger to controversy and embraces the strong divide his art evokes, stating in a 1996 interview that “The work should attract you and repel you at the same time.” However, for many, the killing of animals and their subsequent objectifying treatment as features in museum exhibitions overshadow the meaning of his works.

Though gruesome and shocking, Hirst’s work honestly displays the role that the death of animals plays in the art industry. Pigments, wetting agents, canvas glue, and artist brushes are all derived from a variety of animals and insects. Even if Hirst’s work abided by more conventional standards and omitted the use of full carcasses of animals and insects, his art would still likely result in harming and killing creatures, a fact that he puts on full display in his real work. Hirst confronts the viewer with the reality that the beauty of art comes at the sacrifice of the lives of living creatures whether they are aware of it or not. Still, being honest in the fact that animals are killed for art by further showcasing the problem doesn’t make the act any more ethical, but contributes to the cruelty.

Hirst has contributed greatly to the increase of both live and dead animals used for sculpture and installation in the past few decades, a trend that has taken the use of natural materials to the extreme. However, at a more subdued level, the use of natural materials in art often found in the works of land artists hold the same effective qualities as the works of Hirst. The acclaimed land artist, Richard Long, is much like Hirst in many ways. He too allows nature to speak for itself, rearranging and presenting natural materials in new ways to place a simplicity in his work that evokes strong personal feelings. Long, however, encounters natural materials with love and respect for nature, drawing the line between what makes Hirst and Long’s work so different. Using nature as his limitless canvas, Long brought sculpture to new territories in the 1960s, specifically with A Line Made By Walking (1967) by individually intervening with nature to create sculpture specific to a landscape and time, commenting on the impermanence of nature. Whereas Long appreciates and respects nature in both his art and the creation of it, Hirst’s approach to using natural materials is in no way appreciative. When showcasing dead creatures for his own artistic means, regardless of if they died for the art or not, Hirst is treating the living creature as a mere object, reducing their life to a sculpture or installation and exploiting their remains in the process, whether it be for money or artistic expression, neither justifies Hirst’s objectifying use of animals and insects in his art.

Art from artists such as Richard Long demonstrates how nature and art can unite without unnecessary harm towards it. When done ethically, the use of natural materials in art adds another dimension to the work, connecting the viewer to the powerful forces of nature. Though Hirst’s work achieves this to a great degree, the disrespect and exploitation towards the once-living creatures he uses in his art undermine his artistic intention. Hirst himself said it best: “It’s Beautiful. Only problem is that it’s dead.”