The Arctic is one of the harshest climates known to man. With temperatures dropping to -35 C and lower, and persistent chilling winds, it’s no surprise that this region is one of the least populated spaces on Earth. However, although the population is limited, the presence of community and livelihood is not.

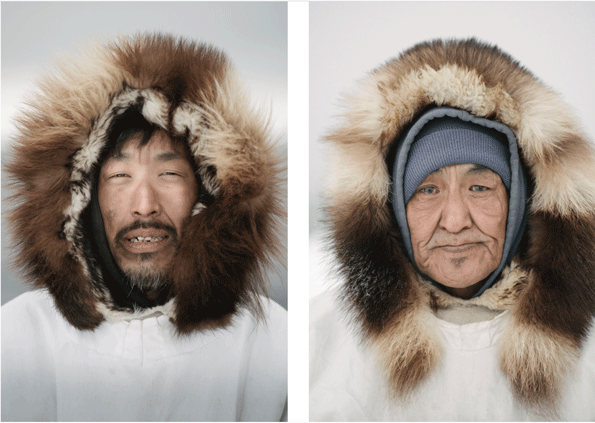

Indigenous communities in these regions have adapted their lifestyles to thrive in the cold and pursue a sustainable lifestyle that honours tradition and the protection of the environment. And while many of these communities seem isolated on the “edge of the world,” Indigenous photographer Kiliii Yuyan embraces the cold to photograph these communities and their unique connection to the Earth while smashing stereotypes about life in Arctic communities.

Identifying as Nanai/Hèzhé (East Asian Indigenous) and Chinese-American, Yuyan has always been drawn to capturing human experience and revitalizing the Indigenous narrative through his lens. His work fights to address the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals of Climate Action, Life Below Water and on Land.

Yuyan once wrote on his blog that “Much of the public perception of the Arctic is based on outdated and colonial ideas of an unexplored and desolate land. That’s certainly not the case, as the Arctic is full of life and community.”

Growing up, Kiliii was naturally attracted to working in nature, living through the stories about Indigenous culture told to him by his grandmother.

“Long before I even understood that my grandmother was Indigenous and what that meant, she told me all these amazing stories and planted the seeds of my love for the land,” Yuyan told The Photographic Journal.

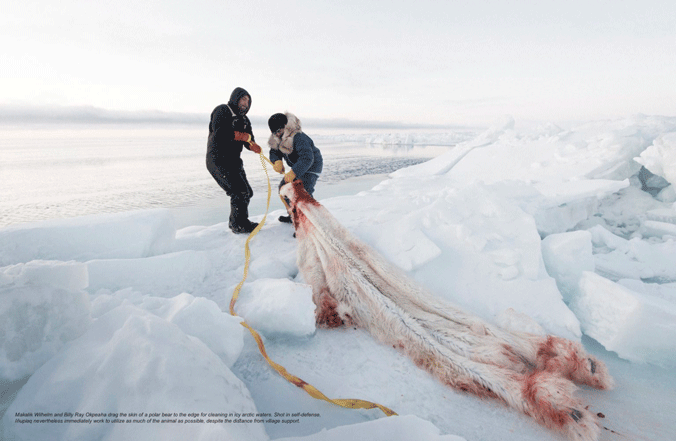

This translates into his work now. In 2018, Yuyan released People of the Whale, a photo series that captures the Indigenous community of the Iñupiaq , who reside on the North Slope of Alaska. This series works to show not only traditional hunting practices (predominantly whales) but the Iñupiaq people’s deep-rooted connection to Alaska. Yuyan describes this series as a piece of resilience, “adapting to the insidious forces of climate change, and Native resilience against globalization through tradition.”

Yuyan’s photo series also highlights how climate change has affected traditional hunting practices. While photographing a variety of communities, Yuyan witnessed hungry polar bears, declining sea ice and a shrinking natural habitat.

“I find it important to highlight how proper stewardship of land in populous regions can help wildlife, and how setting aside land for conservation is increasingly the best solution to our crowded world,” Yuyan told the World Photography Organization.

Yuyan now works to highlight other Indigenous photographers while continuing to document communities in the Arctic, especially Alaska. To learn more about Kilii’s work and his documentation of the ever-changing climate, visit his blog.