In 2004, Domenico and Eleanore de Sole visited the Knoedler & Co. Gallery located in Manhattan's Upper East Side. The couple, who were well-known collectors and patrons of the arts, were interested in buying a painting by emotional abstractionist Sean Scully. It was the first and last time they would visit the gallery. The rest would be determined in a court of law.

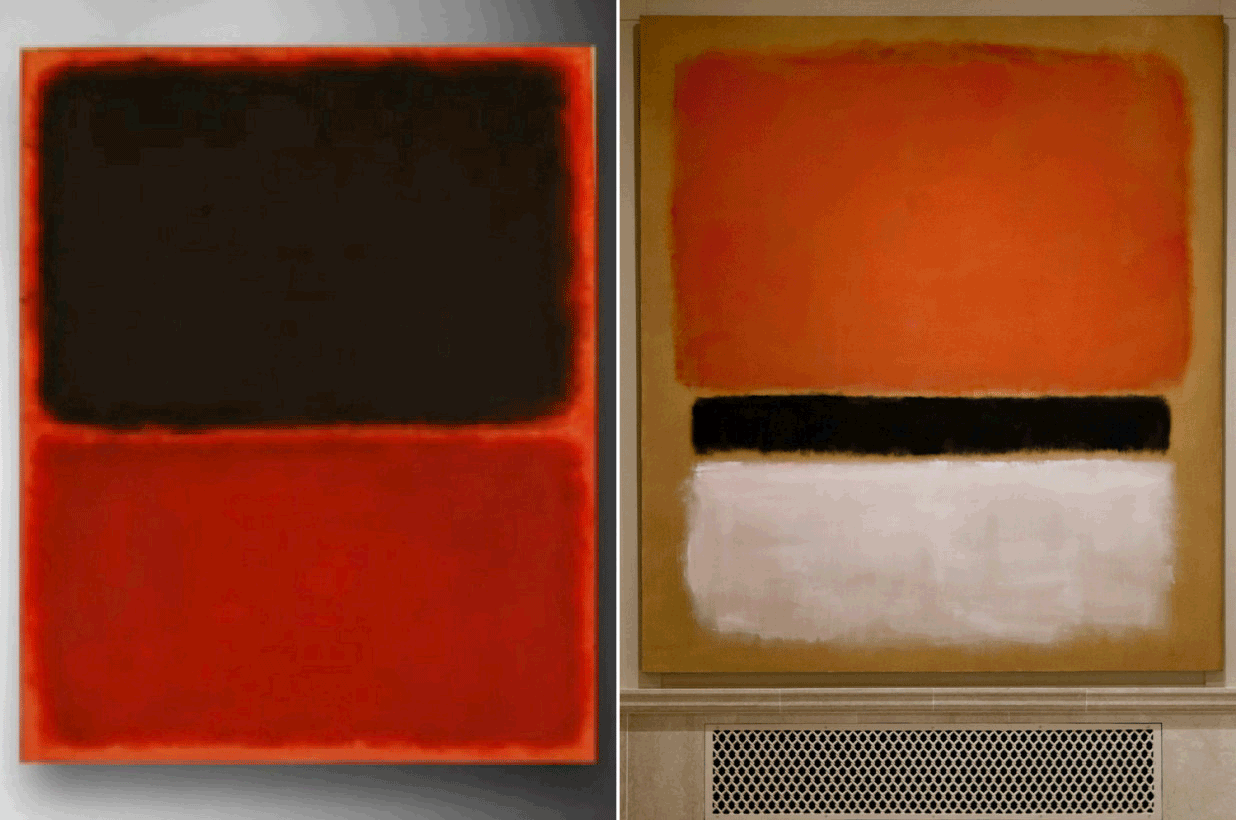

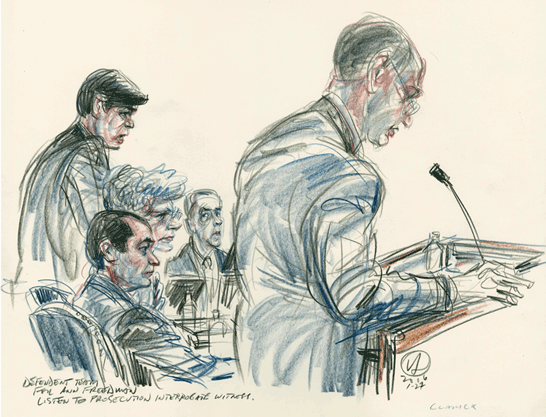

Scully, who led the transition from Minimalism to Emotional Abstraction back in the ’80s, had been represented off and on by Knoedler & Co. for years. To purchase an authentic Scully and acquire proof of authenticity, the de Soles had to speak with the gallery’s president. The couple met with Ann Freedman, president of Knoedler & Co. and famed art dealer, in her lavish East Side Office. Freedman didn’t have the piece they were looking for - but she had a Rothko, right above her mantlepiece. A private Swiss collector, Freedman explained, owned the painting. While the collector wished to remain anonymous, he would sell the painting - for a high price. In the end, the de Soles paid $8.3 million for the work, the most they’d ever spent on a work of art. Ten years later, Domenico would testify that Freedman conned them out of millions. The statement conflicted with his 2004 testimony, where he assured the jury he had “no reason to believe someone was lying.”

In truth, the Rothko was a forgery, one of the dozens passed through the Knoedler in spanning two decades. Between 1994 and 2008, just a year before Ann Freedman quietly resigned, the Knoedler sold more than two dozen forgeries to unsuspecting buyers. The gallery made 80 million dollars from their illicit activities, and Fredman became Knoedler & Co.’s most lucrative president. But the lies didn’t stop there.

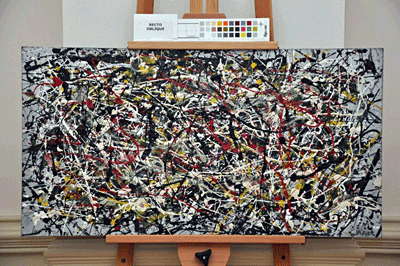

The Swiss collector - known as the mysterious Mr. X, who would be referred to several times throughout the de Soles’ trial - was also fake. Mr. X was the creation of Glafira Rosales, a small-time art dealer from Long Island. From 1994 to 2008, Rosales curated and sold over forty paintings from a former art student named Pei-Shien Qian. She passed them off as Pollocks, Rothkos, and Metherwells that had been “kept secret” for decades. With the help of her boyfriend, Jose Carlos Bergantiños Diaz, and his brother Jesus, Rosales would load the paintings in her car and transport them to the Knoedler. From there, she would hand off the paintings to Freedman, who would forge documentation or perform provenance research that linked Mr. X with the paintings. His name appeared on several invoices throughout the decades, along with more conspicuous names like Alfonso Ossorio, a close friend of Pollock’s.

To make the paintings appear more authentic, Fredman asked various experts to verify the forgeries. For the de Sotos, Fredman secured letters from various Rothko experts. The list included “Laili Nasr, who was making a supplement to the Rothko catalogue raisonné; Christopher Rothko, the artist’s son; art historians Irving Sandler, Stephen Polcari, and David Anfam, the author of the catalogue raisonné for Rothko’s works on canvas.” However, these, too, were forgeries. When Anfam testified in 2016, he claimed to have only seen the piece in photos Fredman sent via email, and this, he added, was long after the de Soto’s purchased their eight million dollar forgery. The other experts routinely made similar statements.

In the end, it wasn’t the de Sotos who unravelled Fredman’s lies. It was a London-based hedge-fund millionaire. The fifty-year-old man was counting on the forgery (a Pollock, according to Fredman) to help divide his assets in a recent divorce settlement. When he sent the painting away for appraisal, scientists found yellow paint pigments invented in the 1970s. (Pollock died in 1956, after a fatal car crash.) The hedge-fund millionaire gave the Knoedler two options: reimburse him, or face the man in court. Instead, the Knoedler astounded the world by rapidly closing its doors. It was a battle Fredman knew she couldn’t win.

By 2012, the scandal attracted international attention. Several other families came forward, each with their own stories about how Fredman had tricked them into buying fake art. By this time, the FBI was investigating two dozen forgeries laundered through the gallery. Eventually, both investigations would culminate in a string of lawsuits that would finally end in 2019.

Roseales, the Long Island art dealer, was the only person who faced the consequences. In 2017, a federal judge ordered her to reimburse the victims to the tune of eighty-one million dollars. Her boyfriend, his brother, and artist Pei-Shien Qian fled to Spain and China, respectively.

As for the Fredman, she and the de Soles settled the matter out of court for an undisclosed amount of money. Today, the case of Fredman and the infamous Knoedler & Co. gallery remains a cautionary tale - and one that proves that you can’t always trust the experts.