Mary Sui Yee Wong is a socially engaged artist. Her work highlights her experiences with gender and racial inequities to carve out a space for Chinese immigrant lived experiences within the predominantly White contemporary art world. In line with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 on Gender Equality and 10 concerning Reduced Inequalities, this conversation with Wong highlighted the pressing need to incorporate more diverse voices in mainstream art.

Wong immigrated from Hong Kong to Canada and grew up in Vancouver, though she currently resides in Montreal. “I consider myself a two-city person, I live in Montreal but I am deeply connected to Vancouver,” Wong said.

Currently, Wong takes alternative formats to presenting art by working with local community organizations and teaching. She is also a part-time faculty member at Concordia University in the Studio Arts Department and a part-time professor at Goddard College in Vermont, founding the Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in socially engaged art within the liberal arts program.

Launched in 2018, this program is based on long-distance learning for students to work within their own communities, creating socially engaged and community-connected pieces.

Socially engaged art ties into both SDG 5 and SDG 10. As a movement within mainstream contemporary art related to social practice, socially engaged art touches on lived experiences, especially concerning gender and racial inequalities.

According to Wong, “Social engagement has a particular political and critical social trajectory. It’s often grounded in feminist and queer theory that allows people of diverse communities to express their lived experiences in a way that’s underepresented in the Western art canon.”

In this interview, Wong talked about her craft, the exoticization of art and art histories, reducing inequalities in her work and her practice as an educator in art.

What inspired you to create art?

“I’ve always wanted to be an artist - in fact, ironically, I wanted to be an opera singer and my father did not encourage it. He did not think that was a good job for an immigrant child to have. He did not come out all the way to this country to turn me into an artist so that I could starve to death.”

However, Wong was inspired by her father’s work as a musician.

“As sifu (teacher), he provided opportunity for the community to find joy and relief from the discrimination and oppression of daily life. Music gave his students an opportunity to express themselves creatively.”

As well, at a young age, Wong felt like she needed creative expression “to put into materials what I couldn’t express in words.”

She came into contemporary art in her thirties.

“When I started looking at contemporary art I noticed there’s a real lack of representation of artists of colour whose work touched me and my lived experiences.”

Then she met Sharyn Yeun.

“She was doing work using hand-made papers to talk about the Chinese immigrant experience. I was incredibly moved by that, thinking ‘God, if art could be used to talk about these kinds of histories and these kinds of stories - if I was ever going to become an artist, that is what I want to use my art to do’. It gave me the impetus, it gave me encouragement, and it was very inspirational.”

How do you choose your mediums and materials?

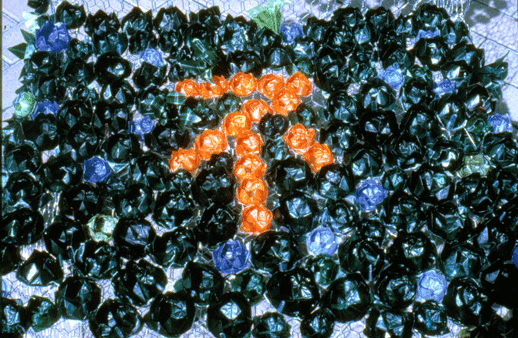

“I was always, first and foremost, looking at how materials themselves carry memories and histories.”

When she started traditional Chinese paper-making, “I was really in touch with myself and my identity. It felt very authentic as a material and as a process.”

It was the first medium that showed her the larger significance of materials. “When looking at hand-made papers, you can’t detach them from their history. I started making things that had some kind of memory that related to my ‘Chineseness’ and I used materials that specifically pointed to perceptions of ‘Chineseness’.”

What do you think about when you create your art?

“I’m really careful about the way that I use histories and bodies of knowledge from my own specificities. I think a lot about how you can misappropriate your own culture and feed into its exoticization. The luxury of being trained in Western contemporary art traditions is so that you know how to play with aesthetics, take advantage and make use of the visual vocabulary. Every viewer comes to your art with a certain subjectivity. They are going to bring their own bias to how they view your work.

“If you can be authentic and grounded in a personal influence, then you won’t exoticize your work. If you over-generalize, that’s when stereotypes and exotification and misrepresentation misperception enter the realm.”

Why does art and art history become exoticized?

“A lot of art history is exoticized because of overgeneralization. Cultural specificity in my work is purposeful. I know I’m going to have multiple audiences, but I am not going to pander to Western audiences.”

Wong noted that she could make her exhibitions more digestible for White audiences, however the point is to spotlight different bodies of knowledge and experiences.

“It’s a way to challenge their own subjectivity. It also challenges the viewers themselves. It puts some responsibility on the viewer to not have the artist do all the work. If you want to understand a culture, you need to make the effort to understand those differences.”

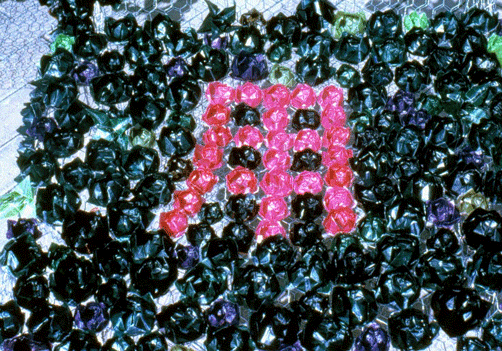

How do you think your art reduces racial inequalities?

“My work was more about addressing racism and how it affected my community and myself as opposed to striving for reducing racial inequalities. They were an effort to bring out the stories, to give voice to a community and an immigrant experience. Inequality is sort of presumed the opposite, that there is equality. It’s a binary relationship between equality and inequality and I feel that unfortunately in this society, racial equality is something imaginary for me.

“As an artist there are certain things that I try to do which have more to do with raising awareness, giving voice to a community, and giving voice to issues. It is definitely culturally specific.”

What is the difference between equity and equality to you?

“Equity for me has more breadth and room to acknowledge the differences but still say that, despite differences, there is also room for people to be on the same platform. Personally, I feel equality is based on the notion that we all have to be the same, equal. I feel like, just by nature when we’re born, we’re not equal. We’re all different. It ignores the fact that there has to be some way to embrace difference.

“I feel like if we’re gonna talk about race in a positive and forward-thinking, visionary way, it has to acknowledge that difference is actually the fundamental cornerstone. Acceptance of difference and acceptance of diversity is how we can break down the colonialistic gaze, the colonialistic ideology that everyone has to be the same by living the Western way and perspective.

“Really the goals of those projects were to highlight the voice of an oppressed community who are underrepresented in art. It’s to show the lived experience of a particular group of people in North America who might not otherwise be showcased if I didn’t do it. It’s about offering multiple perspectives to history, so it’s not all White mainstream history.”

How can educators teach art in a way to minimize inequalities?

“As an educator, I think that, in terms of the art world, we should bring in the notion of decolonization. Within art, it makes a lot of sense. If you’re trying to set up a system in a classroom where you want to encourage students to use art to express their opinions, their personal feelings, their political and or cultural expressions, you have to know how to acknowledge their individuality but also within a collective consciousness.

“Within the art system and education in art, artists are by nature more rebellious and tend to want to express themselves, so no matter what you say is the acceptable way of communicating, they're going to find their own way.”

What are you working on now?

“Most of the work I’ve ever done is always in response to something that’s happening around me. Right now I’m doing a lot of thinking about how I can do that again as a more mature artist. Currently, with the anti-Asian sentiments, we know the world hasn’t evolved that much.

“There’s been a lot of moving internally and thinking about how I can heal my own community.”

Wong aims to do more socially engaged work. “I try to feed my community and create gatherings where people can talk and feel at peace with one another. I call it a part of my art practice because it is that. I use food to enter some of these conversations in other communities.”

While Wong’s work reflects the gender and racial inequalities, pressing topics as highlighted by UN’s SDG 5 and SDG 10, she has generally moved from personal works to becoming more involved with her community. “I’m currently much more interested in an artistic practice that, again, really resides in social justice, community awareness, and so it may mean more community-based projects,” Wong said.

Wong does not have an online gallery, but you can read more about her past installations in our the second part of the interview, here.