When the door to a new way of filmmaking opened with The Wizard Of Oz in 1939, audiences and filmmakers alike were reluctant to embrace colour films, distrusting its likeness to reality. Inevitably, the use of colour in cinema overtook black and white films, becoming a staple in contemporary movies. However, the introduction of colour rapidly blanketed the history of film, leaving black and white movies to be abandoned before their true potential could be realized. Still, the monochrome palette persists today, despite there being no technical need for it, nodding to the innovation still left to be discovered back in Kansas.

With every modern black and white film, audiences search for a narrative purpose, reasoning as to why the filmmaker decided to subvert the norm. In period pieces, this purpose is clear. The nostalgic technique is widely used to recall movies of the past. Films like David Fincher’s Mank (2020) which dives into 1930’s Hollywood to recount the making of Citizen Kane (1941), evoke the past by creating the film as it would have been made in the time it is set in.

Other films, however, utilize black and white filmmaking as a technique in visual storytelling. The beauty of Alfonso Curón’s Roma (2018) lies in its objective intimacy, a quality that can be attributed to the stunning black and white cinematography. The camera is the silent observer to 1970’s life of the domestic worker, Cleo. Though set in the past, the film embraces a modern, naturalistic look, straying from the stylized shadows and high contrast of most black and white movies by utilizing digital film. Applied to the beautiful yet mundane story, the timeless black and white cinematography of Roma does not constrict the film by any specific period, but allows it to play outside of time, not unlike Pawel Pawlikowski’s Cold War of the same year. Cold War’s love affair, set in the 1950’s Cold War in Poland, spans decades, allowing the camera to fill in the gaps. As scenes cut abruptly from one to the next, jumping through time, the film relies on the wordless exposition of the cinematography. When discussing the choice to use black and white, the cinematographer of Cold War, Lukasz Zal stated that “It allows you to build your own interpretation of the world,” and he does exactly that. The cinematography emphasizes contrast at every turn, with bright scenes verging on white, making characters one with the free, vast landscapes of Poland and dark scenes verging on black, making the characters stand out of the darkness and tight spaces of Paris, signaling a shift in emotional tone with the changes in visual composition. Colour in cinema, though beautiful, follows too closely behind real life. However different black and white may be from everyday perception, this separation gives way for artistic interpretation, allowing directors and cinematographers to choose how audiences feel the world of the film.

The power black and white film have in visual storytelling becomes ever more present when used in colour films. The selective use of black and white is exemplified by the works of Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky. The colour of his film Mirror (1975) is drained in the dreamlike, hallucinatory sequences. The use of black and white provides an otherworldly quality while distinguishing between the separate realities in order to aid viewers in comprehending the film’s structure.

David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977) uses black and white cinematography to bring subjectivity. The abstract depiction of imprisoned fatherhood treats the monochromatic imagery as an extension of the characters’ despair. The black and white tones allow the audience to enter the consciousness of the character by emphasizing the grotesque textures and ambiguity of the poorly lit spaces. Similarly, a film of a mathematical genius’s obsession with predicting the future through numbers, Darren Aronofsky’s Pi (1998) uses dirty whites and inky black in combination with a harsh grain to develop a reality of its own. The almost difficult to watch Pi is filmed through the eyes of the protagonist, sharing with audiences the painful perception of an endlessly paranoid and obsessive mind through its visual language alone.

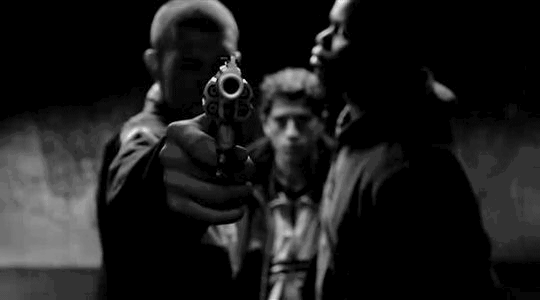

Colour draws the eye to every corner of the screen with its vibrant hues and dazzling beauty, but without it, a film is left bare, stripped of the distractions of colour in favor of the stark truth. Mathieu Kassovitz’s 1995 film, La Haine, abandons its colour, and with it, the too often romanticized view of Paris to uncover the reality of police brutality in relation to its racial and classist inequalities. La Haine’s monochromatic tones also lend the film a universality, setting the story not in Paris, but the world. In a 2020 interview on the film, Kassovitz stated that “the black and white is a trick... to make it universal, a story that happens everywhere, so you don’t know if it’s Paris or Mexico or Brooklyn: it could be anywhere.”

George Miller, director of 2015’s Mad Max: Fury Road, released a black and white version of the film alongside its colourful counterpart, revealing another side to the world of Mad Max. The fast-paced action set against the bright orange sands and teal skies create a visually stunning post-apocalyptic action film, setting it apart from the stale and lifeless colours that have come to be associated with the genre. However, when the vibrancy of the world of Mad Max: Fury Road loses its colour, the film is reduced down to its core elements. Intimate moments hold more emotional depth, violence becomes more gruesome and intense, and the pain of the world is depicted with more truth than could ever be captured in any colour scheme, described by Miller as “authentic and elemental.” However, as George Miller himself admits in an introduction to the Black and Chrome edition, “there’s some information that we got from the colour that’s missing.” Still, for Miller, it is the best version of the movie, “something about black and white, the way it distills it, makes it a little bit more abstract, something about losing some of the information of colour makes it somehow more iconic.”

The timeless quality of black and white films are a reminder of the sameness of humanity, regardless of the film being shot in a time where it had to be black and white, or a time in which it chose to be, monochromatic films transcend time. Although their place seemingly resides in the history of film, the timelessness and the innovative potential of black and white movies will be endlessly explored in the future of cinema, bringing forth the future of film through the visual landscape of the past.