Walter Sickert (1860-1942) was a post-Impressionist English painter, a sometimes-off-putting eccentric, and since the 1970s, a top suspect in the Whitechapel, or Jack the Ripper, Murders of 1888. For nearly eighty years since the string of at least five murders in East London, committed by the unknown assailant, no one had formally accused Walter Sickert of involvement in the crimes. Sickert’s prior association with the Ripper murders were in fact self-directed: the artist was unabashedly interested in the crimes of Jack the Ripper to the point of fetishization. Sickert was known to boast about renting a studio once occupied by Jack the Ripper, and painted a series called the Camden Town Murder while staying there. The Camden Town Murder – which closely resembled the modus operandi of Jack the Ripper – was committed during the time Sickert worked in the supposed Ripper studio. The prospect of Walter Sickert being the most notorious uncaught serial murderer of all time is provocative; the Romantic notion of an unconventional artist being the killer adds another entirely arcane layer to the already compelling mystery. The case for Sickert as Jack the Ripper, however, is improbable at best, impossible at worst. Mitochondrial DNA taken from saliva on stamps suggests that Sickert wrote at least one of the more than six-hundred letters supposedly from Jack the Ripper to Scotland Yard. Drawings on several letters, indications of paintbrush usage, rare stationary, and the self-reference of Mr. Nemo (Latin for Mr. Nobody and an often-used signature in Sickert’s correspondence) indicate that Sickert likely penned many of the notorious Ripper letters to the police.

However, most experts on the forensic details of the case believe that none of the letters received by law enforcement were written by the actual killer. More pressing evidence revealed that there are the multiple family members who made reference to him in letters as vacationing with them in France during the time of the murders in Whitechapel. Though it is unrefuted that Sickert had a predilection for violent imagery, or that his personal life was fraught with issues as a result of his narcissistic behaviour, there is little reason to suspect him of ever having committed a violent crime, let alone the most notorious crimes of the Victorian era. Yet, Sickert remains a perennial favourite in the pool of Ripper suspects, not for the reality of evidence, but for the drama of his persona, and the intrigue of his art.

A Brief Biography

Born in Munich, Germany, in 1860, Walter Richard Sickert was the son of Oswald Sickert, a little-known artist, and Eleanor “Nelly” Henry, the illegitimate daughter of noted astronomer Richard Sheepshanks, whose birth was the result of his long-term affair with an Irish dancer. Growing up under the impression that Sheepshanks was merely her generous benefactor, Eleanor was fortunate enough to be lifted out of poverty by the man she did not know to be her father until she was an adult. Letters written to her by Sheepshanks allude to one-sided feelings of an incestuous nature, which were not reciprocated, and Nelly was cut off from her father’s financial support and communication when she decided to marry Oswald Sickert.

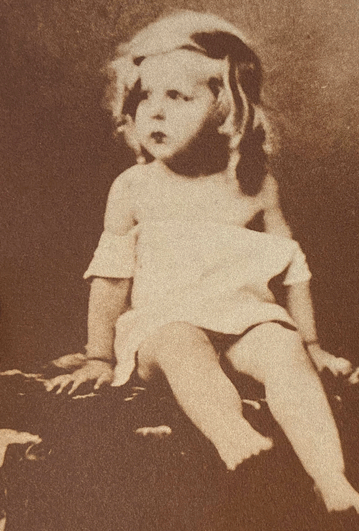

Continuously praised throughout her life for her good looks and charm, Nelly placed a great deal of value on the power of beauty, and in her eyes, none was more beautiful than her perfect boy, Walter. Walter Sickert was the oldest child and one of five boys and a girl, and according to his sister Helena Swanwick’s notes on her childhood, Walter was venerated by their mother for his good looks – he inherited his parents’ flaxen hair and fine features. His cherubic appearance set him aside from his siblings, and Swanwick recalls Walter as a charming but petulant child, who always got his way and became markedly angry when provoked. According to Swanwick, their mother referred to her sons as, “Walter and the boys,” while Swanwick herself was often dismissed due to her sickliness and supposedly homely appearance. This type of childhood dynamic, along with an assumed hereditary predisposition for mental health issues (three of his brothers suffered from depression, two of whom became alcoholics and the other a recluse) are speculated to have resulted in Walter Sickert’s eccentricities and egocentric behaviour in his adult life.

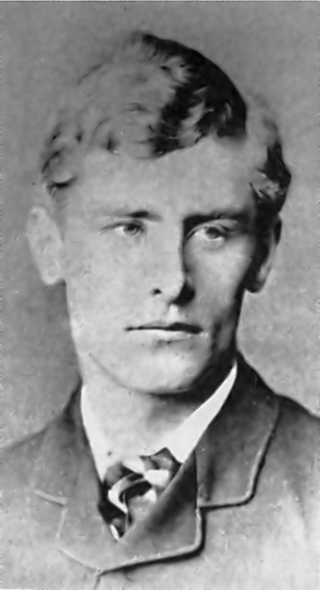

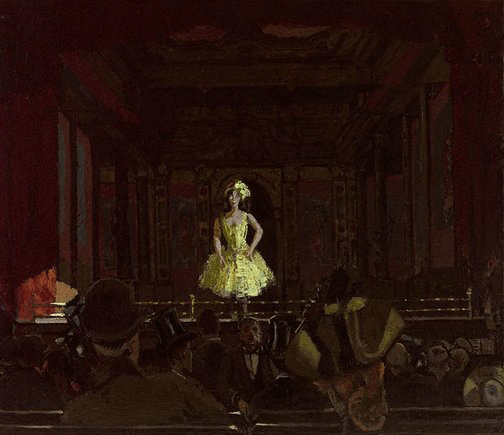

At age eighteen, Sickert began a short-lived career in acting that would span into a lifelong love of theatre, and after playing only a few small parts in Sir Henry Irving’s theatre company, he gave up acting for the chance to study etching as a pupil of James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Though his formative years as a painter were under the instruction of Whistler, Sickert was more stylistically influenced by his friendship with Edgar Degas, whose impassioned brushstrokes, energetic use of spatial composition, and lively subject matter inspired Sickert to paint his own scenes of English nightlife – particularly scenes of theatre. In 1888, the same year as the Ripper murders, Sickert joined a French-influenced group of artists called the New English Art Club and began painting unglamorous renditions of London music halls in his signature dark and muddy palettes. The painting, Katie Lawrence at Gatti’s (1888) sparked a heated controversy over subject matter in art; the depiction of a then-well-known music hall singer was painted in a way that the public deemed vulgar and ugly. Female music hall performers were considered only slightly more chaste than prostitutes, and by conventional wisdom were thought of as pathologically sexual and morally bankrupt: not the type of subject matter to be associated with respectable and academic art. This type of controversy and public denouncement would run parallel to Sickert for the rest of his career. Despite ongoing negative reactions to his art, his social connections, relative fame, and steadfast defense of his provocative work continuously secured his place as a relevant avant-garde artist in rapidly changing 20th century culture.

Was It All an Act? Sickert’s Association with the Ripper

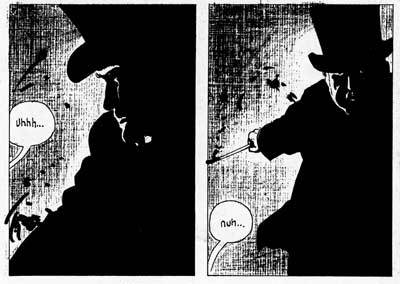

Almost ninety years after the Jack the Ripper murders, the first person to formally accuse Walter Sickert of involvement in the crimes came forward with one of the more famous, albeit absurd, Ripper conspiracies. In his book, Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, written in 1976, Stephen Knight posits a scenario in which the Royal Family and the Freemasons collaborated in secret to kill five prostitutes who knew of a clandestine wedding between Prince Albert Victor and the shop girl Annie Crook, as well as the birth of their legitimate heir to the throne. As the theory goes, the Freemason’s conspired on the part of the Royal Family to rid the world of all witnesses to this marriage and employed one of Queen Victoria’s Physicians-in-Ordinary, Sir. William Gull, to commit the murders. Sickert’s supposed involvement in the conspiracy was said to have been merely as an accomplice; the theory was brought forward to Knight by Joseph Gorman, who claimed to be Sickert’s son, fathered through an extramarital affair. One of the more amusing accounts of Sickert’s knowledge of the Ripper’s identity states that in one of his most famous paintings, Ennui (1913), the meta-painting in the back of the room features a woman looking over her shoulder at a gull menacingly hovering behind her. This was supposedly Sickert’s cryptic allusion to Gull as the murderer of the Whitechapel women. Popularized by Allan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s graphic novel, From Hell (made into a movie in 2001), the Royal conspiracy theory has many versions, all of which are easily refuted. Gorman himself later retracted the story, admitting it was a hoax, and that Gull had suffered a stroke one year prior to the murders and would have been too weak to carry out the physically demanding task.

Despite accusations that Sickert knew of a Ripper conspiracy, he was not himself named a suspect until 1990, when Jean Overton Fuller declared Sickert to be Jack the Ripper in her book Sickert and the Ripper Crimes, though neither the book nor the theory gained widespread recognition. The more recent popularization of Sickert as a top Ripper suspect is a result of the public accusation by crime fiction novelist Patricia Cornwell in her book, Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper – Case Closed (2002). Accused by many to be obsessed with Walter Sickert as Jack the Ripper, Cornwell’s self-funded investigation into the life and times of the artist has borne only the most tenuous pieces of circumstantial evidence. Throughout the journalistically unethical Portrait of a Killer, Cornwell presents unsubstantiated ideas as facts, on which salacious plotlines are built. In the first chapter of the book, it is stated that, “Sickert was born with a deformity of his penis requiring surgeries when he was a toddler that would have left him disfigured if not mutilated. He probably was incapable of an erection. He may not have had enough of a penis left for penetration, and it is quite possible he had to squat like a woman to urinate.” This is the basis for sexual frustration and hatred towards women that Cornwell submits as the root of Sickert’s motivation to kill prostitutes. There is, however, no official record of such a deformity, and while it is on record that Sickert underwent multiple surgeries as an infant, those surgeries were performed by a specialist in anal fistula.

The more considerable point brought up by Cornwell is the mitochondrial DNA evidence she found after funding a test of postage stamps on Sickert’s letters against those found on a selection of Ripper letters. Cornwell claims to have discovered a 1% similarity in mtDNA found in saliva on the stamps, added to which are the vague similarities in style and colloquialisms in both the Sickert and Ripper letters. Long before Sickert was ever accused of being Jack the Ripper, an acquaintance, Quentin Bell, described Sickert as a prolific letter writer, whose style was, “ garrulous, unbuttoned post-prandial [and] full of wandering reflections and scandalously imported anecdotes.” The same is certainly true of many of the Ripper letters, but it is agreed upon by professionals that writing Ripper letters was a common enough practice among the public, and that it is impossible to authenticate any piece of correspondence in which the writer claims to be the killer. At the very least, it is plausible that Sickert may have been among the hobby letter writers posing as Jack the Ripper. In his memoirs, Clive Bell (Quentin Bell’s father) describes Sickert as an actor in life: “one day he would be John Bull and the next Voltaire: occasionally he was the Archbishop of Canterbury and quite often the Pope.” Bell also recounts Sickert shouting, “God-damn Christianity!” at a group of salvationists on the street, and referring to a maid in his studio as, “beautiful but an awful bitch really,” as she waited on him. Sickert’s love of the macabre and his tendency to alienate and provoke those around him are not the subjects of which best-selling crime novels are written, but accusations of murder aside, Sickert’s erratic personality and the art created in its reflection are altogether fascinating in their own right.

A Painting by Any Other Name

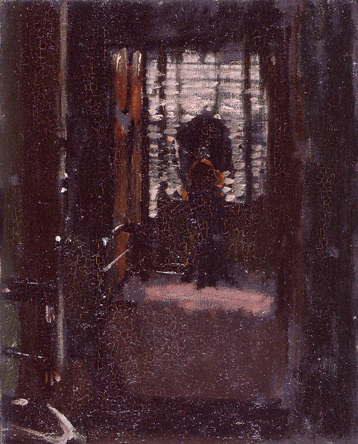

Walter Sickert once remarked while lecturing at the Thanet School of Art in 1934, “we like a good murder.” We, in this case, probably refers to the masses, though he went on to describe in more detail his personal preoccupation with the murder, and specifically the murder of Emily Dimmock in Camden Town that occurred in 1907 while he was lodging in a studio nearby. Sickert rented the studio after the landlady told him that she had suspected a previous tenant of being Jack the Ripper. One of the first paintings he produced in the studio is titled, Jack the Ripper’s Bedroom (1907); Whistler’s influence can be seen in the rendering of this painting, with its strong geometric composition and harmonic layering of crimson and brown pigments, creating an almost black depth. The ambiguity of the figure, however, along with the tension created by the abysmal vortex of the receding shapes is unique to Sickert. The composition draws in the viewer, but without the comfort of Whistler’s realism and precision; instead, the off-balanced lines and alla prima brushstrokes convey a sense of urgency and disorientation.

Not long after channeling the Ripper in his painting, another media sensation occurred. Emily Dimmock, who worked as a prostitute, was killed by a client in her room in September 1907. The mass amounts of media coverage rivaled that of the Ripper murders, and though the Dimmock murder did not sustain an enduring public fascination, the two cases bare much in common: violent and sexually motivated killing of women, media sensationalism fueling the public interest, and the status of the case remaining unsolved. The trial drew more than 8000 people to the courthouse to watch as the accused, commercial artist Robert Wood, was acquitted. Sickert claimed to have used the image of Wood as his model for the subsequent series of paintings based on the murder, a trio of paintings that still incites controversy to this day.

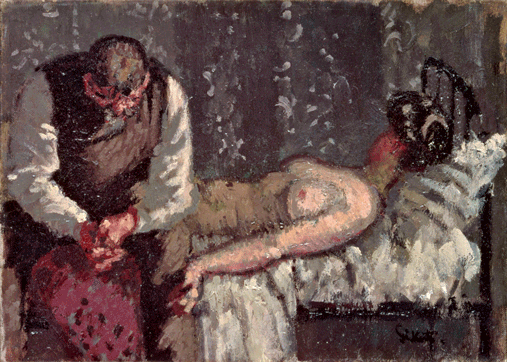

Exhibited in 1911, L’Affaire de Camden Town (1909), What Shall We Do For Rent or The Camden Town Murder (1908), and Summer Afternoon or What Shall We Do For Rent (1908) were displayed under the series title, The Camden Town Murder. Art historian Rebecca Daniels states that the reference to the murders, “[was a] clearly desperate attempt to appeal to the press,” noting that Sickert, who had a confusing habit of changing the titles of his paintings years after their creation, had been working on another series of domestic narratives while creating the Camden Town Murder paintings. Daniels argues that the titular painting of the Camden Town Murder series was originally called What Shall We Do For The Rent?, and was added to the exhibition erroneously as a bid for more attention.

Portrait of the Psyche

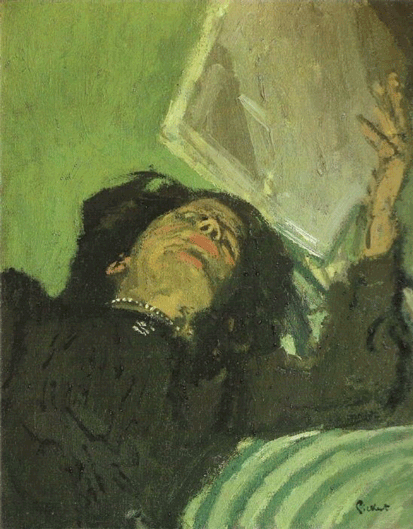

While direct reference to murder remains the most noted and controversial aspect of his career, it is the unmistakable violence evoked in the form and style of Walter Sickert’s art that is most fascinating. In a 1910 letter, Sickert referred to modern life as, “this terrifying world,” and was consistently outspoken about his preference for painting scenes of urban decay, debauchery, and poverty. Regarding models, he preferred women of what he called “haggish appearance,” as well as obese or emaciated women, and once wrote a letter to a friend delighting in his model’s dirty clothes and claiming that he would not look at a woman under forty. The sum of these parts equals a stark realism approach to art making; it is, however, the expressionistic manner in which he painted women that illustrates a more sinister and complex mindset.

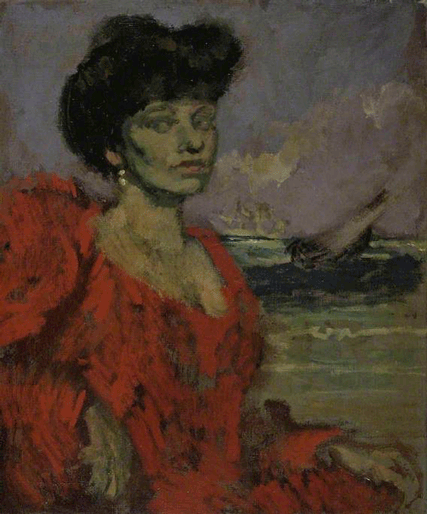

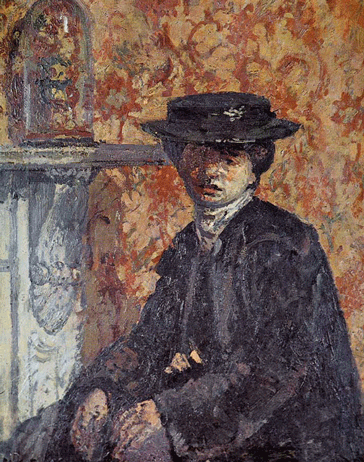

There have been many indirect statements made by Sickert that allude to an underlying misogyny; though it was not uncommon at the time for men to dismiss, mistreat, or refer to women as “bitches and hags,” Sickert’s paintings seem to reveal a more violent assertion. Often painted with a look of shock or horror in their eyes, many of the women in Sickert’s portraits were painted with a ghastly pallor of green and grey, juxtaposed with bright and visceral swathes of deep red. The red is most often expressed as clothing, but in the case of Portrait of Ethel Sands (1913-1914) there are two thick lines of bright red protruding from the crook of the neck at the left shoulder of the subject, and recurring in her lips, eyes, and ears. A more alarming depiction of a woman in portrait is The New Home (1908), in which the impasto use of red is applied to the right side of the woman’s face. Her expression is otherwise slack and saddened, perhaps an ironic nod to the idealism of the title but disclosing instead a seething proclivity for visually enacting women in danger.

A recurring motif in Sickert’s paintings is also a perceived hint at his true identity as Jack the Ripper, although is more likely an unconscious display of his fascination with the Ripper and of the murdered women. Often seen are exaggerated renderings of necklaces or scarves around a female subject’s neck, sometimes with red or pink streaks running downwards from what can be mistaken for a wound. Other images seem to portray the female subject’s as dead, at harsh angles, strikingly similar to the published newspaper photos of Ripper victims.

The identity of Jack the Ripper is a story indelible for the intrigue of its mystery, and the idea of Walter Sickert as the Ripper is exactly that: a story. There is little compelling evidence to implicate his guilt and several key pieces of evidence to support his innocence of these crimes, and most experts have dismissed him as a suspect. Yet, the name Walter Sickert will be forever linked to Jack the Ripper, and perhaps not undeservedly so. The violent expression in Sickert’s work and his sensationalist leanings epitomize the depravity of the culture surrounding the Ripper murders, the crazed consumption of lewd sensationalism, and the unresolved cycle of hostility that demands it.