Roughly two miles of the iconic Los Angeles’ roadway, Venice Boulevard, separates the greater L.A. districts of Culver City and The Palms. At the approximate median point of the Boulevard’s two miles is the odd and inconspicuous entrance of the Museum of Jurassic Technology (MJT), located on the corner of Bagley Avenue and Venice. The outside appearance of The MJT stands out from other businesses in the area–– its olive-green stucco façade is accented by a marble garden-wall-fountain. At the top of the building, between three sets of window panes, the green paint on the stucco is peeling off. It has a caged teal-green door that remains closed and only opens when visitors enter inside.

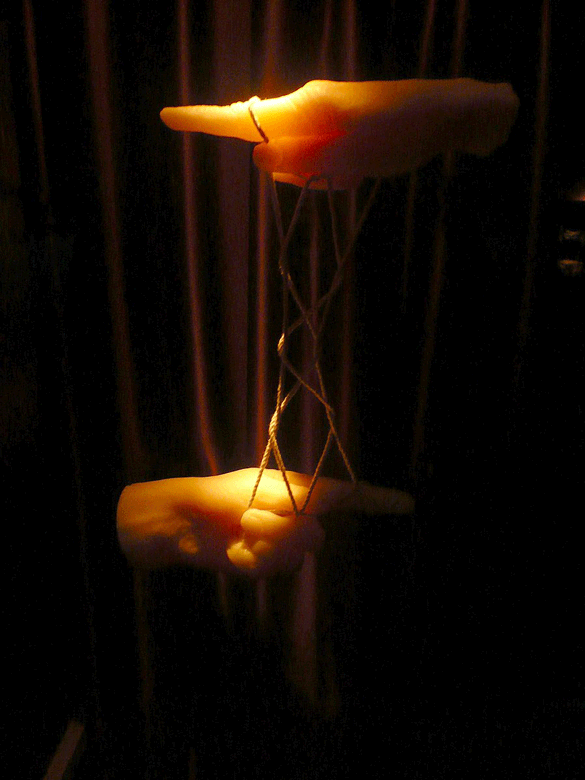

The inside of the MJT is all the more peculiar –– directly behind the entrance door is a cramped and dark gift shop selling items exclusive to, made by, and referential of the museum, such as porcelain sculptures, 3-D View-Masters, and informational catalogues. Past the gift shop, the museum’s space is substantial, containing 10-12 galleries, three levels, and even an outdoor courtyard on the top floor. The museum’s galleries showcase curious oddities like dioramas, taxidermy, miniature sculptures, and more. Its exhibits are extensive and diverse, presenting collections of materials such as a library concentrated solely on Napoleon Bonaparte, a room dedicated to the comprehensive history of Cat’s Cradle, and a portrait gallery of paintings that commemorate numerous Soviet dogs who were sent to space in the early 1960s. The MJT is a museum of natural history, science, folklore, ethnography, and art –– a place that gives visibility to a depth of odd and peripheral knowledge that most museums wouldn’t consider valuable.

Initially founded in 1988 by David Wilson and his wife Diana, the MJT is “an educational institution dedicated to advancing knowledge and the public appreciation of the Lower Jurassic” (MJT). Most viewers enter (and leave) the museum with the same question in mind: what is the Lower Jurassic, and what is Jurassic Technology? For a visitor of this museum, the answer may never become factually clear; however, that is precisely the point of an encounter with the MJT that makes it different from other museums. The MJT does not give its visitors any answers, and it does not claim any veracity to its teachings.

In his early career, Wilson studied filmmaking and experimental animation at the California Institute of the Arts, earning a MFA in 1976. As the MJT’s leading curator, Wilson’s influence of cinema and animation trickles into the DNA of the museum. The galleries are dim, and various sources of light faintly light objects. Discernibly cinematic in nature, the MJT uses methods of storytelling to contextualize its exhibits. Didactic information about the history of objects and exhibitions is communicated through sound recordings, animations, videos, and even holograms. With the unusual presentation of items, the unique transmission of information, and the peculiar nature of objects on display, the MJT offers an unconventional museum experience to a viewer.

Viewers often leave the museum questioning the factual accuracy or the “truth” of the objects on display. Every exhibition in the MJT is “based on” a real moment, item, or work of history; however, the museum takes liberties to alter the meaning and perception of the items and narratives it exhibits. A portion of the MJT’s daily visitors are dissatisfied with their experience. Most viewers enter with the expectation of encountering a conventional museum: a place that systematically presents facts and histories. Instead of offering its audiences concrete information, as many natural history museums do, the MJT encourages viewers to piece together their understanding of archival objects and historical knowledge.

In their influential essay, The Universal Survey Museum, art historians Carol Duncan and Alan Wallach argue that “The museum's primary function is ideological. It is meant to impress upon those who use or pass through it society's most revered beliefs and values” (449). Through its apparatuses, the MJT challenges viewers to contemplate the type of information and belief systems that museums are commonly indebted to. The International Council of Museums suggests that museums serve society by acquiring, conserving, researching, and communicating tangible and intangible aspects of heritage and humanity for education (ICOM). With this definition in mind, it is essential to remember that museums’ are often subjective about the type of information they preserve; most institutions are tied to colonial beginnings and colonial systems of preservation, presentation, and education.

Through careful curation of unique objects, spaces, and narratives, the MJT encourages viewers to question what they know and understand about institutions and histories. These considerations are particularly relevant for audiences today, as many people and organizations are calling for the decolonization and re-contextualization of museums. Above all, the MJT asks audiences to critically consider information –– even if the source is as credible as a museum –– before accepting it as truth, fact, or fiction.

Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic, the MJT is currently closed to the public. Patrons can support the museum during its closure by purchasing from or donating to the MJT through its online gift shop. All proceeds go towards the operation of the museum.