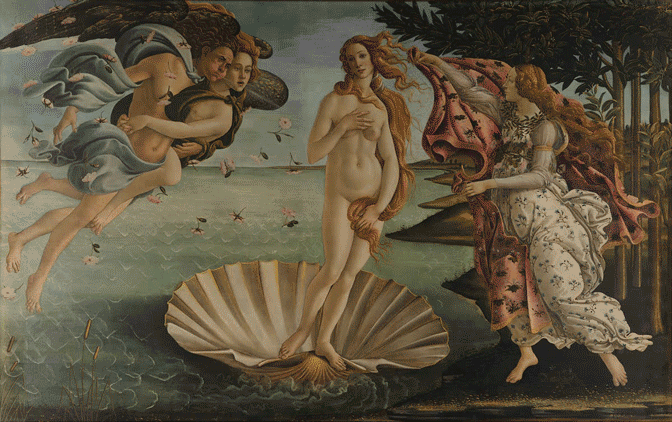

Artistic reinterpretation of mythology, particularly Greek and Roman mythology, plays a vital role in how these stories have come to be viewed and understood. Works such as Botticelli’s The Birth Of Venus (1483-1485) have become permanent extensions of Classic mythological stories and figures. As art defined mythology, mythology subsequently left its impact on art. With the endless potential for reinterpretation, the stories, figures, and symbols of mythology provide artists with a vast source of symbolic material. As a result, mythology is constantly mutating to best suit the artists' need to express themselves, yet the core themes presented in mythology remain unchanged. As disconnected from reality as mythology may seem, just beneath the surface of the fantastical stories lies universal truths of the human condition. Through the exploration of intrinsically human themes, mythology becomes a means to understand the world with philosophical inquiry, leaving artists to turn to the fantastical stories to process the truth of their realities.

Expressing Political Anguish

Artists often turn to mythological metaphors in an attempt to process and understand the horrors of their time. The use of iconographical imagery allows for a level of objectivity needed to gain perspective on social or political struggles. Consequently, much of the mythological art of the 19th century and onward uses Classical mythology as a backdrop to express the artist’s perspective on social and political events such as war.

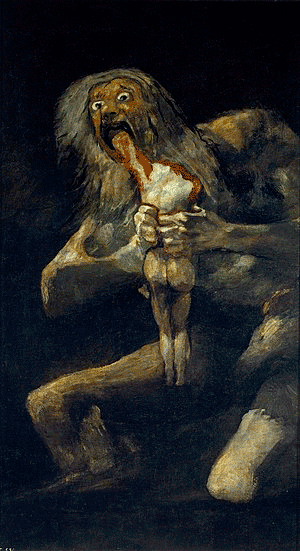

In a response to the Napoleonic Wars, Spanish painter, Francisco Goya created The Black Paintings, a collection of fourteen works painted directly on the walls of his home, only to be discovered years after his death. The outstanding piece of which is Saturn Devouring His Son (1820-1823). The Myth of Saturn tells of the Titan who ruled the earth, but was prophesied to be overthrown by one of his sons. Saturn, set on keeping his power, ate each of his sons as they were born, all except mighty Zeus, who was hidden by Saturn’s wife, Rhea. Zeus would grow to fulfill the prophecy and overthrow Saturn’s reign.

Goya’s painting is likely influenced by Peter Paul Rubens’ 1636 painting of the same name. However, whereas Ruben’s depiction of the myth is much more accurate to the original mythology, Goya strays from the story, imparting his agony onto the canvas. Goya depicts Saturn with weakness and shame in the reclamation of power rather than pride. Saturn encapsulates himself in darkness, as if mortified by his acts. With grief in his eyes, a ravenous urgency overcomes the Titan, white knuckles tightly grasping his half-devoured son, desperately holding onto the token of bright red, blood-soaked power. The powerful and respected Titan is no less than a monstrous creature in Goya's depiction. The artist further alters the myth by having Saturn devour not a baby, but a full-grown figure, suggesting that it is Zeus who he is killing before he can overthrow his father and fulfill the prophecy. This alteration reflects Goya’s pessimistic perspective that he carried with him throughout his later years as a result of the state of his home country. Goya witnessed Spain violently fall apart with Napoleon’s invasion to keep and obtain power. It is clear why Goya resonated with the themes of the myth of Saturn. The abuse of power and destruction out of fear of being destroyed run through the veins of both the mythology and Spain at the time of the Napoleonic Wars, themes which he further accentuated from his perspective through the distortion of the myth.

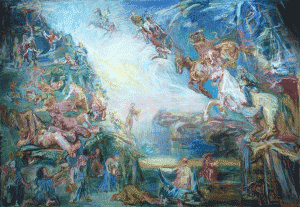

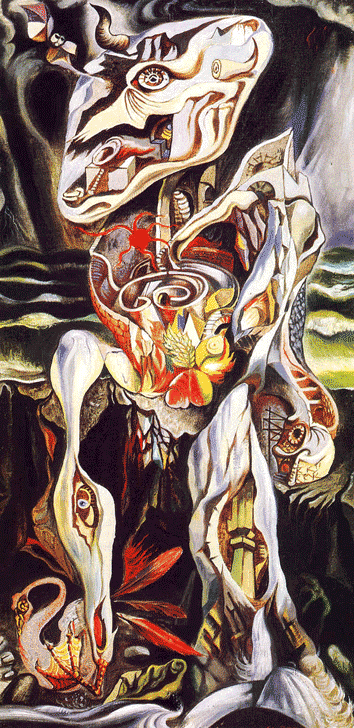

As artists shifted away from strict adherence to mythological stories and towards depicting them more poetically and personally, WWII uncovered the true savage and animalistic nature of man. Inevitably, art from this period is riddled with mythological symbolism, tapping into the deeper, humanistic roots of the fantastical stories. Oscar Kokoschka’s The Prometheus Triptych (1950) tells of man’s self-destruction as a result of reckless ambition and misplaced pride. The artist stated that the painting is a warning of the consequences of “man’s intellectual arrogance” symbolized through the mythological figure, Prometheus who, in an act of overconfidence, stole fire from the gods. In response to WWII and the impending threat of nuclear warfare, the painting was made in fear of the loss of compassion and humanity in pursuit of scientific and technological advancements.

As a warning to humanity on the right panel, Kokoschka depicts Prometheus as a symbol of humanity, displaying his punishment of having an eagle pick at his liver forever in eternal torture, with a vision of the apocalypse and the four horsemen leading a storm rising from the underworld in the center panel. The painting evolved as an almost prophetic piece as Kokoschka’s fears came to fruition with the cold war and the nuclear arms race in the following years.

Understanding The Self

Freudian interpretations of Classical mythology became a pervasive subject among artists looking to examine the self, reaching its height in the mid-1900s. The tale of Theseus, who conquered the depths of the labyrinth by slaying the Minotaur, particularly resonated with surrealists. Surrealists overtook the depiction of the Cretan saga with a psychological perspective rooted in Freudian psychology as man's journey traveling through the labyrinth, representative of the mind, to reach its depths, or the inner psyche after conquering the minotaur, symbolic of the id. André Masson’s fascination with the Minotaur in multiple works throughout 1932-1945 is believed to be responsible for the resurgence of the Minotaur and its psychoanalytic interpretations in 20th-century art, predating some of the creature's more prominent interpretations, including the works of Pablo Picasso. Masson’s relationship with the Minotaur is at its most complex in The Labyrinth (1938), which explores the unconscious with, of course, great Freudian influence. Inversely, in Masson’s strangely paradoxical depiction, the minotaur has absorbed the labyrinth, adding another layer of depth to the original mythology. The haunting imagery of The Labyrinth dives into the depths of the subconscious with green seas just above a vast, black abyss. The labyrinth inside the minotaur traps unpleasant memories and forbidden thoughts buried deep within the psyche. The choice to contain the labyrinth within the very thing that must be destroyed to reach its depths demands the question of how must one overcome the id and reach their innermost self when the id encompasses the inner self.

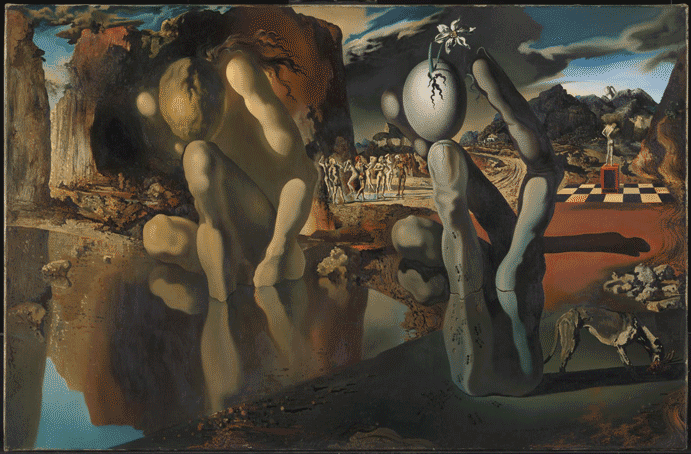

Additionally, Freud’s work on narcissism inevitably made its way into artistic depictions of the story of Narcissus, most notably in Salvador Dalí’s Metamorphosis Of Narcissus (1937). Dalí presents elements of Freud’s work on both narcissism and the unconscious to represent the three stages of Narcissus’s transformation into self-absorption. In the myth, Narcissus fell in love with his own reflection in a pool of water. Paralyzed with his beauty, Narcissus eventually died staring into his reflection, leaving behind a flower that would come to be named after him. In Metamorphosis Of Narcissus, Dalí enacts this transformation of life and beauty to obsession and death in a single piece. Narcissus is seen as a statuesque figure staring at his reflection, and through the use of Dalí’s archetypal double-imagery, is also seen as a stone hand of the same figure, drained of life. From his death, however, springs hope as the Narcissus flower births from an egg held by the stone hand. However, the eye is drawn to yet another depiction of Narcissus, but before his self-absorption, standing on a pedestal just behind the foreground. Freud’s work had a great impact on Dalí, which culminated in Metamorphosis Of Narcissus. When meeting Freud in 1938, Dalí brought with him this painting with hopes of discussing the psychology of narcissism and the unconscious. Although Freud was rather unresponsive to Dalí’s inquisitiveness, he later wrote that until he met with Dalí, he was “inclined to look upon the surrealists – who have apparently chosen me as their patron saint – as absolute… cranks. That young Spaniard, however, with his candid and fanatical eyes, and his undeniable technical mastery, has made me reconsider my opinion.”

An Overdue Perspective

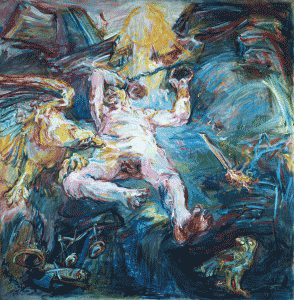

Mythology and its universal themes have been reinterpreted by artists throughout time as a reflection of humanity, yet not all of humanity is represented. Mythology as it has come to be known, exclusively favors the heterosexual white male perspective, leaving behind those who identify as women, LGBTQ+, and people of colour. Although the stories of same-sex relationships are told throughout mythology, adaptations of such stories have been ignored or re-written to change the nature of the relationship in both literature and art. Similarly, many people of colour from mythology, such as Andromeda, have been whitewashed through history’s broken telephone and obsession with Eurocentric features, erasing their presence in mythology entirely. Women, on the other hand, have an undeniable role in both mythology and its artistic and literary adaptations, yet their place in it is secondary to men. Female mythological figures played the roles of witches, manipulators, monsters, and helpless victims to develop the storyline of the heroic male, reflecting the outdated societal values of ancient Greece and Rome. However, modern artists such as Ithel Colquhoun are reclaiming their place in Greek and Roman mythology.

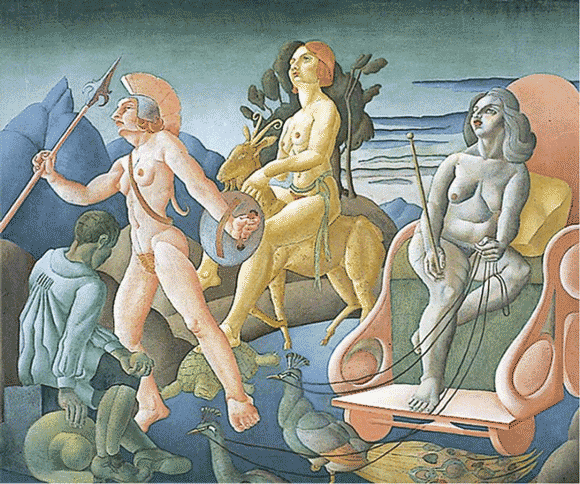

Ithell Colquhoun chose to challenge the traditional gender roles of classical mythology, interpreting the women of mythology in a much different light than the artists before her. The Judgement Of Paris (1930) depicts what is ultimately described as a beauty contest between Athena, Aphrodite and Hera, judged, as the title explains, by Paris, a mortal prince. Whereas other artworks of the scene, such as Peter Paul Ruben’s 1636 painting of the same name, depict the goddesses as objects to be examined by the male gaze, Colquhoun shifts the power dynamic. The goddesses are no longer to be examined but respected. Their powerful, elevated presence dominates the painting as Paris humbly bows his head in admiration. In contrast to the vulnerable and delicate depictions of earlier artists that have come to be associated with the women, Colquhoun’s version demands a re-telling of the characterization of Athena, Aphrodite, and Hera in which they are not defined by their beauty, but their strength.

Comparing contemporary struggles to that of Classical mythology attests to the universality of the human experience. Immortalized through art, mythology continues to be a constant inspiration for artists to explore, owing to the essence of humanity which runs through all mythological encounters. As myths are reinterpreted time and time again through the eyes of the artist, the result holds the weight of their experience, adding another layer of depth to the mythology for the next artist to be inspired by. The stories of ancient mythology and art have proven to be forever entangled, yet the depiction of such stories doesn’t have to hold the same discriminatory qualities as past iterations have. Reinterpretations from modern artists bring opportunity for these stories to be retold as they should have been all along to truly reflect all of humanity.