In the last 29 years, 200,000 people have died after overdosing on prescription opioids. With numbers so large, it is hard to fathom the individual impact on families and loved ones, let alone imagine what we could do in the face of mass tragedy. Nan Goldin became a part of the statistics along with thousands of others who became addicted to oxycontin, but after battling through her addiction she became a David to the pharmaceutical giant that is Purdue Pharma.

Perhaps David and Goliath is the wrong analogy. When the villains are so large and their misdeeds are so well hidden, narratives of singular heroes do not suffice. This is something photographer Nan Goldin well knew when she harnessed her creative prowess and the power of community to become a massive thorn in the side of this giant.

Goldin started taking pictures when she was 15 and has since had a transgressive and illustrious career. Her most famous collection of photographs is The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, which has been exhibited worldwide at the Whitney Biennial and film festivals. These “snapshot-style” portraits show scenes of youthful passion, love, addiction and abuse in intimate details, reflecting both the artist's life and the reckless era of the time. Her work continued to reflect her life and so her themes matured with her into more domestic scenes of parenthood. She has been said to take “pictures of things we do not wish to see.”

“I was obsessed with recording my life. The major motivation for my work is an obsession with memory,” she said in an interview.

In 2014, Goldin was prescribed oxycontin for wrist pain and like so many unsuspecting patients quickly became entangled in the web of this highly addictive drug. She eventually began seeking the drug on the black market and mixing it with other drugs until she overdosed after three years of torment.

Goldin describes her addiction as an almost full-time job. “And I got clean. I didn’t know about the crisis. I only knew about my own crisis. And I found out pretty quickly about the crisis, but I still didn’t know about the Sacklers,” she said in an interview.

In 2017 she got clean, describing it as an incredibly dark period in her life in an interview with The New York Times:

“Your own skin revolts against you. Every part of yourself is in terrible pain.”

Oxycontin was produced by Purdue Pharma, a company run by some members of the Sackler’s up until 2019. Since 1999 there have been 200,000 opioid overdose deaths in the US because of their misinformation.

Purdue Pharma marketed this drug with incredible and swift aggression in marketing campaigns that painted the drug as safe and non-addictive. They sponsored medical courses, lobbied lawmakers, bribed doctors and flooded the market with prescriptions.

Later the company would claim not to know about the addictiveness or the abuse of their drug. However, recent reports show that in the first year of the release of the drug in 1996 they were already aware of widespread abuse and addiction and covered it up with more marketing rather than pulling the drug or attempting to regulate prescription.

When Nan Goldin heard that Purdue Pharma was the producer of this drug, the Sackler name rang a bell for her. The Sackler family has been lining the pockets of the world’s foremost museums—the Met, the Guggenheim, Tate Modern and the Louvre, for years and had their names plastered on these cultural institutions.

Goldin founded the activist group PAIN (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) after her recovery. The group’s goal was to connect Sackler’s misdeeds in the pharmaceutical industry with their misleading philanthropic dealings. “We’re here to call out the museums who allow the Sackler name to line their halls, tarnish their wings, to honour the family who made billions off the bodies of hundreds of thousands,” Goldin said during a protest. At the group's 2018 protest they dumped hundreds of fake OxyContin bottles into a reflection pool, one of many powerful protests she and her group helped organize.

In 2019 her group staged a “die-in” at the Guggenheim. Dramatic and impactful, their protest drew the eyes of the work to Mortimer D.A. Sackler, who was on the board of the museum, when they dropped thousands of prescription slips down the infamous spiral.

Goldin refused to have her work or retrospectives showcased in the Guggenheim until they stopped boasting the Sackler name or taking their funds. Not long after, the Met, Tate Modern and the Guggenheim refused to continue their relationships with the Sackler family.

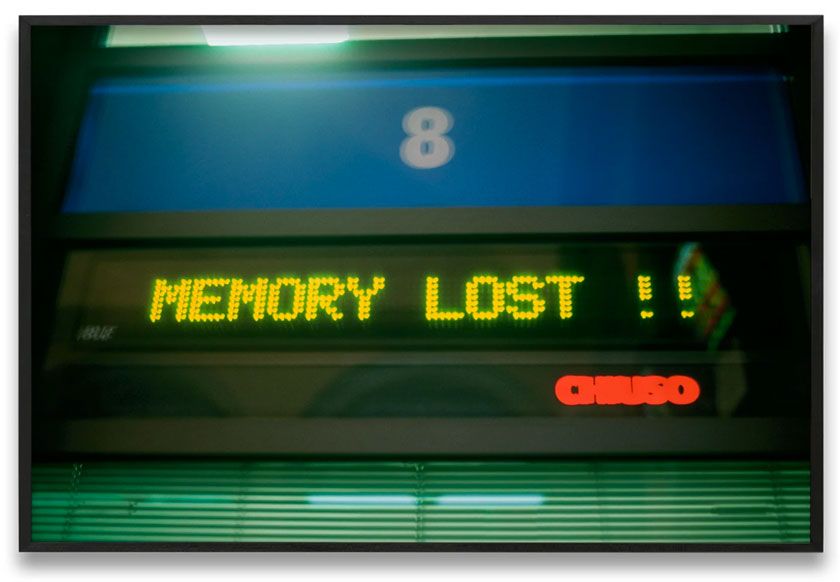

Her series Memory Lost is a slideshow of her life in the midst of addiction. The photographs are intimate and overwhelmingly familiar at times and beautiful and strange at others.

Patrik Radden Keefe, the author of Empire of Pain, which detailed the aggressive and immoral marketing campaigns of Purdue Pharma, also detailed how Goldin was tailed by private investigators tracking her every move in response to her incredible international protests.

“With her impeccable eye and the zeal of a survivor, Goldin framed each protest like a photograph,” Keefe wrote. “She pioneered a powerful new form of activism and started an urgent conversation about tainted money in the arts.”

The Sackler family has been ordered to pay up $6 billion in remediation after years of justice being miscarried. This is by the effort of artists and activists like Goldin but also by the invisible efforts of whistleblowers, lawmakers and families fighting for decades to bring about justice.

Her campaign to end the harm done by the Sacklers and Purdue Pharma is both art and activism. Her work supports the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for Health and Well-Being and Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions. For these efforts, she has been awarded as one of Time magazine's 100 most influential people of 2022.