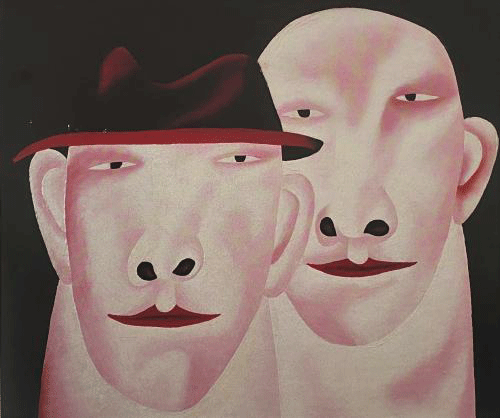

Five grotesque faces emerge from the darkness, each with the same chilling expression. Part human, part monster, their hollow eyes and gaping mouths bear an ambiguously tormented expression that oscillates between pain, anger, and sadness - a spectrum of human suffering.

These are the phantom faces that appear again and again throughout the work of late Russian painter Oleg Tselkov, whose artistic practice would come to be characterized by his unique and haunting representations of interior psycho-violence in the modern world.

Though he is now lauded as one of the greatest Russian artists of his era, his native country did not view his provocative paintings quite so favorably. Deeming Socialist Realism the only ideologically acceptable artistic style, both Tselkov and his works were banned by the Soviet Union, whose oppressive regime was marked by innumerable human rights abuses, highlighting the importance of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal on Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions.

Expelled from his home, Tselkov settled in Paris in 1977, where he worked for the rest of his life up until his recent death on July 11, 2021 at the age of 87.

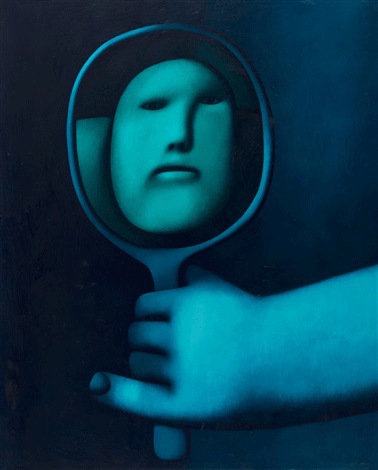

In Soviet-era Russia, the communist ideology of the state sought to eliminate the individual in order for the whole to succeed, resulting in sinister practices of forced assimilation and constant surveillance, policing both the body and the mind. The government’s attempts to manipulate and control the inner thoughts and feelings of its citizens - a psychological attack on individuality - resulted in widespread trauma across the U.S.S.R. From this culture of fear, Tselkov’s famous portraits were born.

In 1960, Tselkov painted the first of many mutant faces. With eyes, ears, a nose and a mouth, the figures gazing out from the canvas may be human, but they are not people. They are everybody and nobody, humanity reduced to a single eerie visage.

Amazed at the mystery of his own creation, Tselkov recalled that fateful day, saying,“I then painted a sort of portrait, not taking the subject as an individual, but as a portrait that is universal, collective, united in one character. Not a face, but a mask, a countenance with a horrible familiarity.”

Through these bone-chilling “portraits” Tselkov put onto canvas the invisible effects of psychological violence that a person suffers when their individuality - the very thing that makes one human - is stripped away, leaving only the darkness of human nature behind.

For forty years, Tselkov painted these mysterious faces, asking them one question each time: “Who are you?”

He never got an answer, so he kept painting. What he does know for certain is that somewhere within their empty eyes, these faces hold an enduring, immutable truth about humanity. “It is clear to me that they have a thousand years behind them and an eternity ahead,” he once said of his creations and the knowledge that they possess.

As popular as they may be today, Tselkov never intended for his paintings to be likeable. Rather, he wanted viewers to be disturbed into looking inside themselves and learning something about humankind. Though his work was in part a response to the oppression of the since-fallen Soviet Union, it has not lost its relevance. In a world where human rights are under constant threat, Tselkov’s monstrous faces will live on eternally, just as he said they would, remaining as ghostly reminders of what makes us human in the first place.