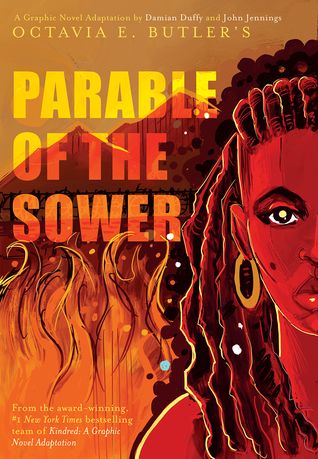

Envisioning the future often comes at the cost of identity. In looking at the myriad of dystopian art forms, be it film, literature or visual art, many intersections of oppression and identity vanish. Class and gender often live at the surface of these stories, while race, nationality, sexuality and disablement fall to the wayside. Parable of the Sower, a novel written by Octavia Butler in 1993 that was adapted into a graphic novel by Damien Duffy and John Jennings in 2020, challenges the universal tone taken by post-apocalyptic narratives.

Referred to as the “Grand Dame of Science Fiction”(although she disliked the age associated with the title), Octavia Butler (1947-2006) produced a collection of literature in her time that pioneered Black storytelling in the predominantly white realm of speculative fiction. Butler wields the immense potentiality that speculative fiction holds for marginalised characters in her favour. And true to form, Butler’s Black characters, like herself, are tethered to their Blackness — be it in the past, present or future.

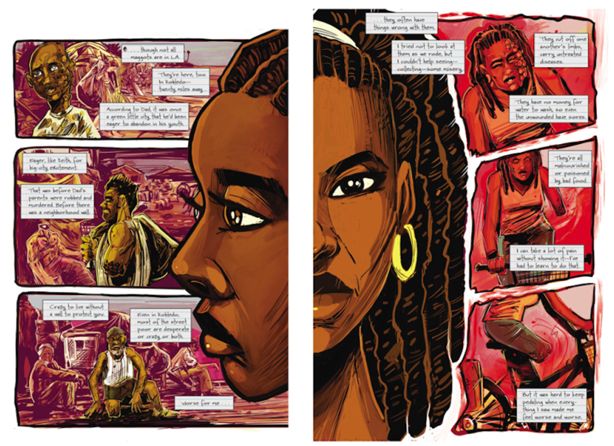

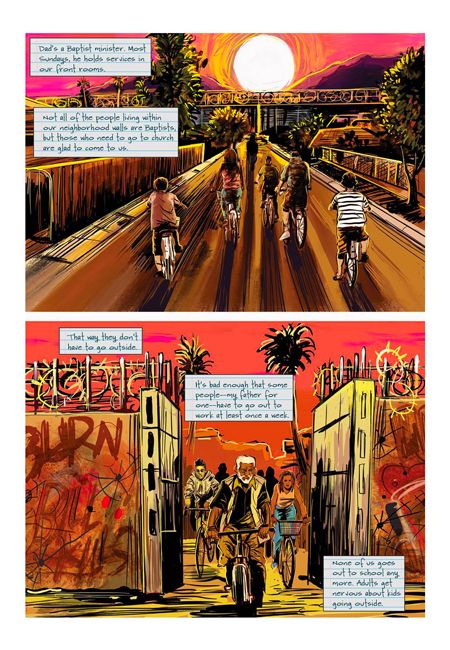

Her tale, Parable of the Sower, stands as the first novel of an unfinished trilogy. In a future frighteningly close to ours, Lauren Olamina begins her story in 2024. She lives with her father, a preacher, within a gated community in Los Angeles. Protected from the raging environmental, economic and social crises beyond the walls, Lauren’s hyperempathy — an ability to sense the emotions of others developed from her biological mother’s drug use during pregnancy — centres the atrocities that occur in the story. Her faith, which she names “Earthseed”, allows her to migrate across the country and sustain belief amidst the chaos of climate change, the increasing wealth gap, classism, sexism, racism and xenophobia.

Parable of the Sower plays out as a future history. In an interview in 2004 with Joshunda Sanders discussing the parallels between the novel and reality, Butler said, “Keep in mind that when I wrote them, Bush wasn’t president. Clinton had yet to be reelected. When I wrote them the time was very different. I was trying not to prophesize. Matter of fact, I was trying to give warning.”

Duffy and Jennings ground this concern in their adaptation of the novel. Adaptations seem to be a difficult terrain to navigate, with issues surrounding both their similarity and difference to the source material. While some may feel that the graphic novel does not offer anything that the novel does not, there is perhaps some greater inclination to read the original novel alongside the graphic adaptation. Duffy and Jennings' recreation of Butler’s book visualises the piece with all its due complexity.

“Parable of the Sower is quite dark,” said Damian Duffy about the novel. “It was the first book I ever had to put down because it scared me, and that was one reason I really wanted to adapt it. But in going over it again and again, in sifting through every devastating and brutal part, you start to realize that those aren't the point, the point is that Lauren, the protagonist, goes through all that and still keeps going. She finds places to put knowledge, understanding, and kindness, even in the bleakest, the most hopeless of realistic worlds.”

The illustrations make an attempt at honesty considering that it does not deviate from the narrative nor any commentary given by Butler herself. This effort remains especially important as Butler’s work is regularly debated amongst academics and the public alike, even when she has clarified certain points herself - such as the debates surrounding Kindred‘s (1979) science fiction qualities despite explicitly being labelled as a work of fantasy.

In the graphic portrayal, Butler’s words maintain the intimate perspective of its protagonist. The handwritten notes across blue-lined paper seem to be torn from her diary and pasted onto the images.

The vignettes of Laura’s story, enmeshed with the density of climate and social decay, survive as a testament to what can be birthed from destruction.

Harsh scribbled lines distract from the static, smooth nature of the page, detailing movement. Strokes of colour flesh out the horror and hope sketched onto the pages. The jagged lines, the rich and deep hues, and the dissimilarity between each and every page captivate an audience with a vibrant dynamism that sits at the heart of the novel: God is change, and change is our only constant.

The rhythmic movement from page to page echoes a world that seems to change from one moment to the next, where those marginalised are under constant threat — especially with climate change cementing longstanding injustices. The Parable of the Sowers articulates the concerns and need for the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals of Reduced Inequalities, Sustainable Cities and Communities, Climate Action and No Poverty.

Butler’s work reads as a lamentation of our times. But we have yet to arrive at the future Butler wrote about in 1993. Like the unknown ending of the Parables series, we don’t know what the future holds for us. Butler, and subsequently Jennings and Duffy, warn us against the violence of what could be and of the communities we must protect.

Find out more about Jennings and Duffy’s Parable of the Sower: The Graphic Adaptation here. Octavia Butler’s books can be found here. Both copies can also be found at many bookstores internationally.