“I paint my own reality,” the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo once said. Over the centuries, women artists have used painting as a creative outlet to express their emotions, frustration and pain in response to trauma and personal tragedy and as a form of therapy. Others have painted to explore their sexuality and as a social critique against conventional norms of marriage, femininity, and motherhood. Kahlo did so with numerous self-portraits of her damaged and broken body following childhood polio and a horrific teenage bus accident that led to a lifetime of physical and psychological suffering. The renowned seventeenth-century Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi used painting to assert her artistic identity and visually punish the art instructor who raped her.

Similarly, 26-year-old Detroit-based CHamoru femme artist Gisela McDaniel, a 2017 BFA graduate of the University of Michigan, draws upon personal pain to create exquisite portraits of healing and resilience. “Trauma never goes away,’’ she says in an interview with Arts Help, acknowledging that she has PTSD from having been sexually assaulted both as a teenager in Cleveland and in college while studying abroad her sophomore year. “It’s how you process and move on from it that matters,” she states. For McDaniel, art has been a coping mechanism allowing her to explore her relationship with her body following sexual assault. She began by painting self-portraits and recording herself describing the shame and self-loathing involved with having had her body violated, creating a kind of audio diary documenting private pain before she felt comfortable enough to discuss the experiences with others.

The first self-portrait she painted upon returning to university from abroad was of herself wearing a ski mask she recalled in a July 1, 2021, interview with SEEN magazine. The mask theme endured in subsequent portraits of survivors and others, such as Conversation on a Pink Couch (2019), Hinasso: Over My Måitai (2019), Over Heated (2018), Coexist (2018), and Deep Roots Blurred (2019).

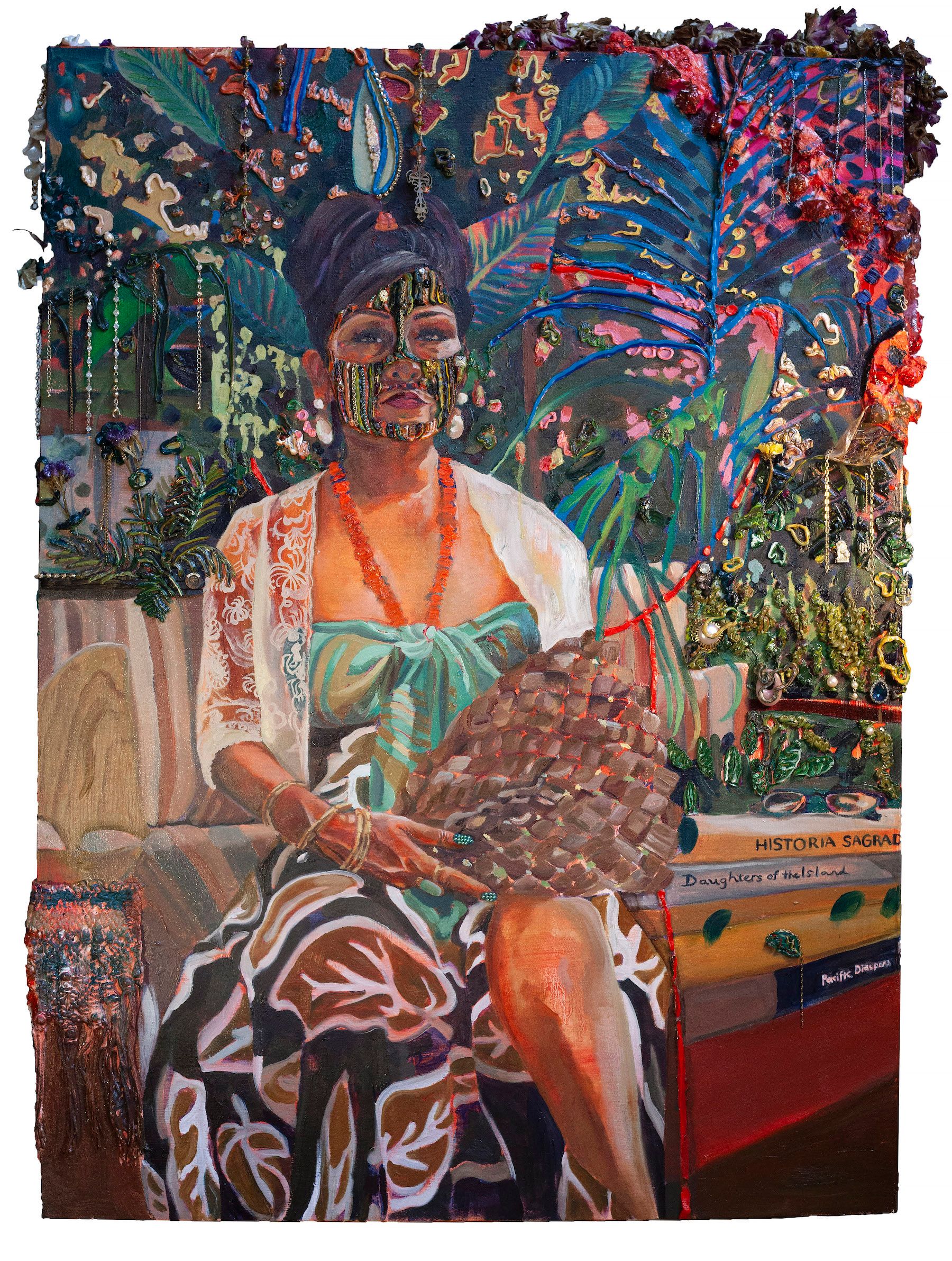

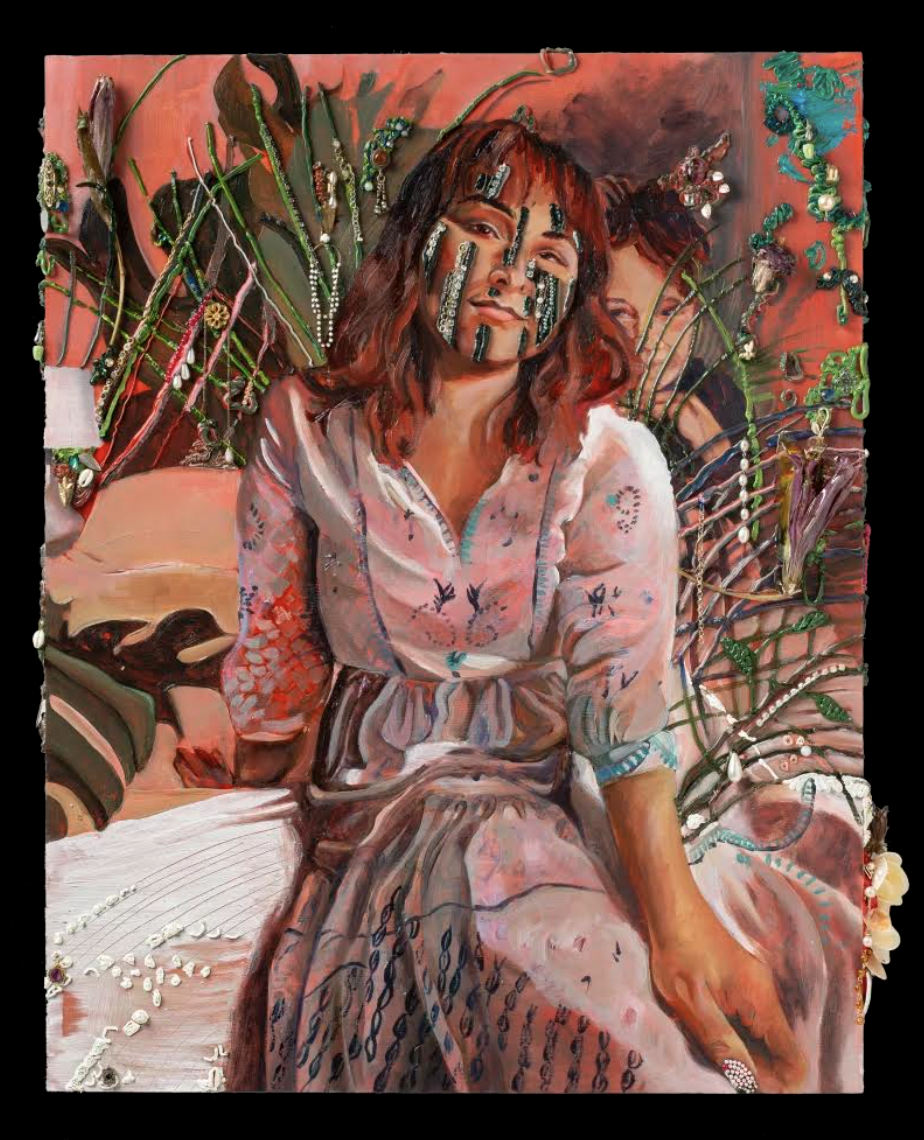

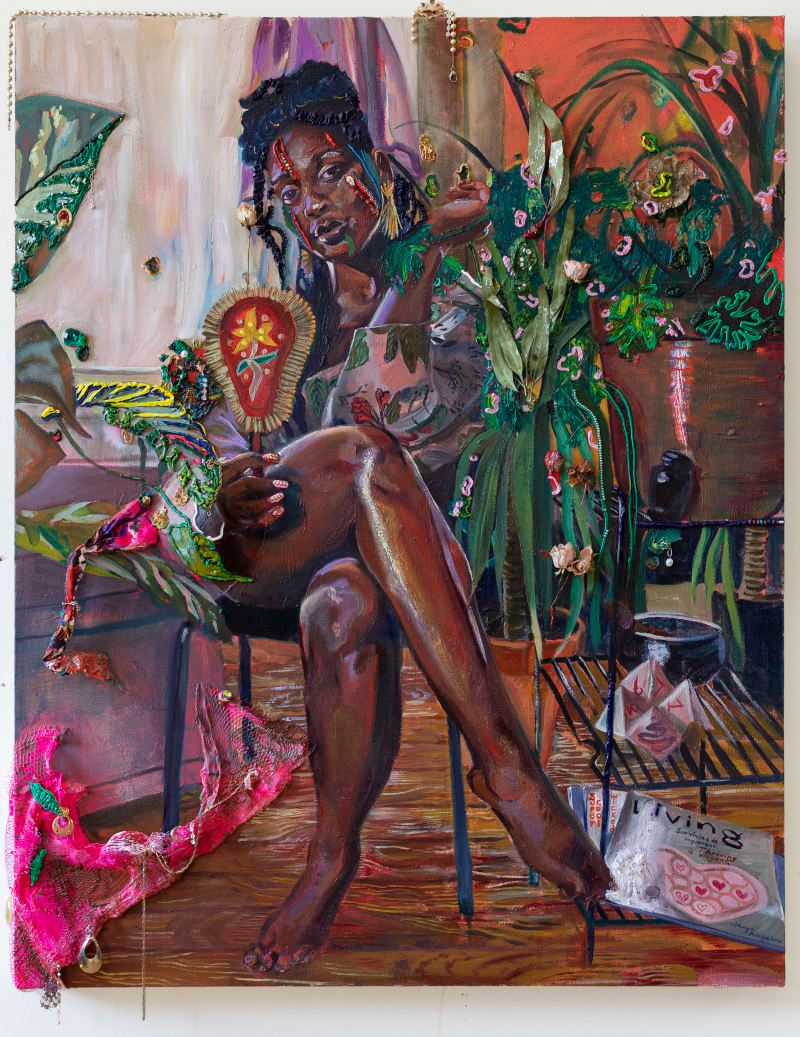

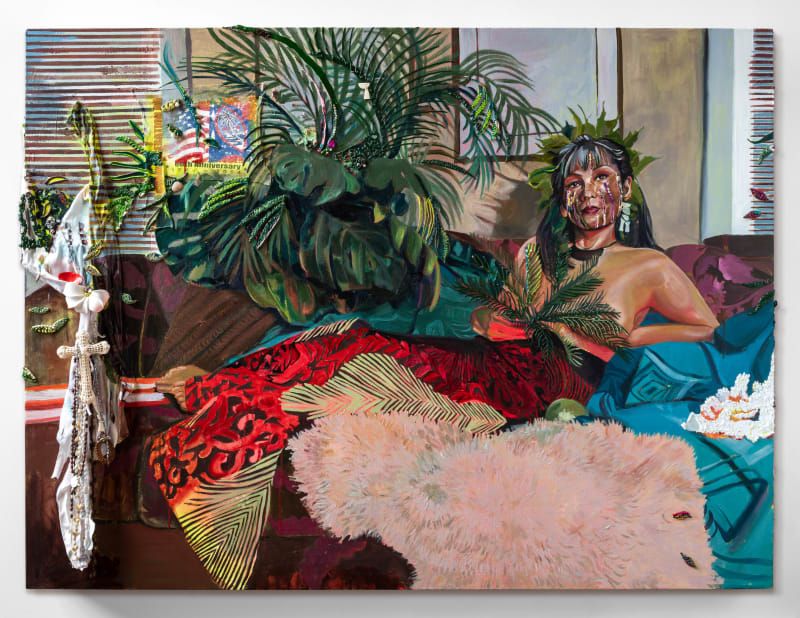

In other paintings, faces are not so much masked as washed with colour or striped with designs that only nominally obscure the identity of those portrayed. Some examples are Complex Faces (2020), Ha’abak (2020), Presence (2020), What She Saw, Where She Went (2020), and Tiningo Si Sirena (2021, a portrait of McDaniel’s mother), as well as later self-portraits such as Movement (2020). Either way, the result is warrior-like, emphasizing the resilience and strength of the individual.

Currently a 2021 Kresge Foundation Visual Artist Fellow, McDaniel, identifies as a diasporic indigenous CHamoru artist, primarily painting women-identifying and nonbinary people of the BIWOC community who have endured sexual violence. Incorporating oil paint, resin, mixed media, artificial flowers, fabric, jewelry and found objects onto the surface of her portraits, McDaniel is as much an artist as she is a storyteller, documentarian and social activist. Not only does she explore sexual violence in her portraits, but also racism, colonialism and gender identity. Since many of McDaniel’s portraiture subjects are indigenous women, womxn, and nonbinary people of colour who have also survived assault, her work intersects with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on Gender Equality, Reduced Inequalities and Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions.

McDaniel’s experience as a mixed-race indigenous woman informs the themes she explores. Born on a military base in Bellevue, Nebraska, to a CHamoru (the preferred spelling of the CHamoru people) mother from Guam and a white father in the U.S. Navy, McDaniel was raised in Ohio where her mother is a sociology professor specializing in comparative race and ethnicity studies. The CHamoru are the indigenous people of Guam and the Mariana Islands in the North Pacific Ocean. Guam is an American territory, and many of her maternal relatives reside there still. She has been based in Detroit for the past four years working out of a studio in the New Center area since graduating from the University of Michigan Ann Arbor with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Art and Design in 2017.

Growing up in the Cleveland area, McDaniel admitted to Arts Help that she felt out of place because of her mixed heritage. She was either “not white enough” to be included in predominantly white spaces or excluded from those with other BIPOC artists for having lighter skin. Her gender and youth have also been issues of discrimination in the past, as she has often been perceived as naïve and inexperienced by patriarchal, white male-dominated institutions despite her prodigious talent.

McDaniel weaves audio from recorded interviews with her subjects confiding their stories of surviving sexual assault into her work. She mixes and distorts the files to ensure no individual voice can be identified with any portrait to protect the sitter's privacy and anonymity, nor are any subjects named, many of whom fear retaliation from their abusers/attackers. An embedded sound recording accompanies each portrait that is triggered by a motion sensor on the surface when an observer moves near, producing works that literally “talk” to the viewer. By interweaving the voices of survivors, McDaniel also subverts traditional power relations between victims and perpetrators, enabling individual and collective healing.

The people in McDaniel’s paintings come from diverse backgrounds. Some are friends, friends of friends, or personal acquaintances, while others are strangers who have reached out to McDaniel wanting to unburden themselves in a safe space where they will not be judged, stigmatized or blamed for what happened to them. McDaniel told Arts Help that people come to her by word of mouth, referral from other survivors, or reach out to her over social media. She keeps in touch with many former “collaborators,” checking in from time to time. Speaking with someone who has undergone a similar experience and being treated with kindness, compassion, and empathy helps one process pain.

Each portrait McDaniel paints becomes an artistic collaboration between artist and subject, as individuals relate their stories to McDaniel while she paints. Indeed, McDaniel calls her sitters “collaborators.” They are not models or artistic muses posing to have their likenesses painted at the whim of the artist, as historically done by white male artists in Western art. As McDaniel explained to the Detroit Metro Times in a July 6, 2021, interview:

Everyone I work with is so much more than a muse…. I seek people out because I want them to be heard and remembered for their brilliance and strength, although I wish so many didn't have to exist in a world that required them to be resilient. I hope to imagine and build that kind of world together.

Through her portraits, McDaniel elevates her subjects, challenging patriarchal norms of censorship regulating the display and exhibition of women's bodies, voices and stories. McDaniel’s collaborators exude strength and resilience; they are not objectified or passive. Rather, they are ordinary people whom McDaniel has elevated through her paintbrush to the level of fine art portraiture. Their frank, direct gazes challenge the viewer to take notice.

Under McDaniel’s brush, the individuals are far from helpless, vulnerable victims, but the persevering survivors that they are, painted with sensitivity and empathy. As she described to the Detroit Metro Times:

Each painting is made to celebrate each individual, so they are inherently all very unique to the person, there are many hints in objects and embellishment, but I often choose not to explain them because they are ultimately for the subject and their loved one’s knowledge. After our conversations, they sit for the paintings. Some donate broken jewelry and old clothing to integrate into the piece. It feels like an exchange and a practice of gift-giving.

McDaniel says the objects and embellishments in the paintings serve as “intentional and consensual artifacts” that her collaborators have chosen to be remembered by that have personal significance to them. Some of her subjects are portrayed nude or draped; others are clothed in outfits of their choosing. They pose in colour-saturated spaces filled with plants and rich with detail–an almost tropical atmosphere.

The lush backgrounds and botanical elements are reminiscent of French Primitivist painter Henri Rousseau and the vivid colors of Paul Gauguin’s Symbolist/Synthetic works in Tahiti, adding to their psychological and visual intensity. In addition to Kahlo and Gauguin, McDaniel cites the exuberant work of French American sculptor Niki de Saint Phalle as an influence.

Regardless, McDaniel subverts the patriarchal male gaze traditionally associated with women and especially female nudes in Western art. Her collaborators are active subjects with agency, not passive or submissive. Each portrait challenges the viewer to apprehend as the aggregate stories play out on a USB loop. She hopes that people who see and hear the work develop empathy and compassion for those who have been violated, including any past sexual predators or perpetrators themselves, so they might better understand the pain they inflicted.

With this verbalization, McDaniel seeks to break the pervasive culture of silence surrounding sexual violence and trauma especially among indigenous women and women of colour who often avoid speaking for fear of disbelief or retaliation from their attackers/abusers and out of the feelings of shame, disgust and self-loathing they may harbour. As she explained to The Michigan Daily in an April 15, 2021, interview:

I’m really interested in creating these portals where [my subjects] can speak through…. I had a sensor embedded in the surface of the painting. And when you stepped within like three feet, [the painting] would talk to you. So, the story would start to speak. You can’t enter the personal space of the painting without hearing that sound or hearing that person’s voice or their story.

The added audio element encourages a dialogue between subject and viewer to enable collective healing and make conversations about sexual violence and trauma less taboo in the BIWOC, femme, womxn and nonbinary communities. Although McDaniel does not consider herself or her work explicitly feminist, her portraits exude a feminist vibe in their articulation of a clear female gaze. Subjects are not sexually objectified, idealized reclining nudes or the Classical Venuses traditionally associated with Western art. They possess agency.

The ongoing pandemic forced McDaniel to paint portraits from photographs people sent to capture their likenesses rather than in personal sittings at her studio. In April 2021, McDaniel became involved in a public art installation on behalf of people affected by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic in partnership with the Los Angeles-based non-profit art space and global platform, The Mistake Room (TMR) in Downtown LA, which opened May 7, 2021. Called Things With Feathers, the series of public murals is inspired by the American poet Emily Dickinson’s poem beginning, “ Hope is the thing with feathers.” The trio of public art projects was organized by TMR for Art Rise, part of the WE RISE initiative of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, to shed light on loss and grief and the toll COVID-19 has had on people’s lives and mental health while imagining ways to heal and persevere.

For Things With Feathers, The Mistake Room’s trio of projects for Art Rise, McDaniel conducted interviews with individuals in Los Angeles and elsewhere whose experiences with violence shed light on the injustices and inequalities that the pandemic has exacerbated. She recorded stories and created a soundscape to accompany a public mural of her collaborators highlighting many facets of healing. The mixed media installation, entitled Sakkan Eku LA on the façade of TMR’s building at the southernmost edge of Downtown LA, is on view until December 21, 2021.

To find out more about Gisela McDaniel, check out her profile and paintings on the Pilar Corrias Gallery website and Instagram. And, to see even more of McDaniel’s paintings, or to submit an online request to be contacted for a portrait, visit her website here.