With its captivating visual art style, attention to detail and musical soundtracks, the mass appeal of Studio Ghibli films ought to be considered an art form in and of itself.

Studio Ghibli films are unconventional art forms in the cinematic world. They’re known best for their dynamic storylines and characters, scrupulous attention to detail, and capturing the essence of fantasy in everyday settings—all while promoting pacifist and environmental messages. Researchers who have studied Japanese animator and Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki say that his art is moreso a living being that combines the ethics of nature with human nature through intriguing, world-building aesthetics.

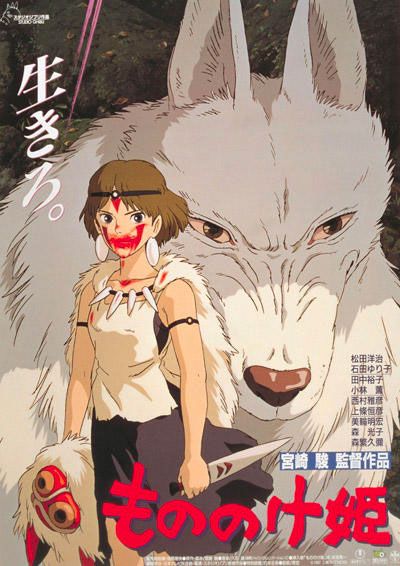

The film Princess Mononoke (1997) is a realistic example in a fantasy setting. Its most important themes are aspects of natural and human nature, natural beauty and purity of wildlife without the urban footprint left by humans. The trademark message is that opposing nature—whether ours or of the natural world—is our ultimate doom.

This film also serves as an excellent example of environmental advocacy and encourages oneness with nature against war, industrialization, deforestation, environmental disasters and wiping out the indigenous wildlife. Humans and the wildlife are spiritually bound to a sacred spirit, a literal and figurative symbol for life, flourishing and nature. The story is set in 14th-15th century Japan where young prince Ashitaka, in saving his village from a wild boar attack, inflicts a curse on himself. In his quest to find a cure, he sees humans decimating nature and all living creatures that live within it, which instigates wars between humans and the wolf-god Moro, and his teenage companion San (or Princess Mononoke).

Lady Eboshi is the strong-willed morally grey antagonist who seeks to empower her village in respect, riches and equality. She employs social outcasts from back then—women and people suffering from leprosy—to process iron and manufacture weaponry and machinery. While her care for her people is sincere, Eboshi built the village by clearcutting forests to mine and process the iron, which led to conflicts with the boar god Nago.

Eboshi’s methods are questionable, but her vision is a black mirror to human tendencies. She justifies destroying the environment for iron simply because it is a means of getting a status “back into” society and will make her town well-known. Her vision for her village is heartfelt and touches the viewer, but her greed goes overboard. Our underlying need and greed for constant improvement anchors on our use of finite resources which can only go on for as long as our planet has these finite resources. Once they run out, monetary value will be attached to other things, and the motivation and pressure for environmental sustainability may reach the nadir point.

The scenes depict humanity’s destruction of peaceful nature for their selfish uses, leaving a trauma surging in nature through their footprints. All throughout, the interconnectedness of nature is shown in a mystical, wondrous light, and draws on spiritual intimacy as a way of connecting oneself with, literally, their environment. But the end of the story entails Ashitaka and San’s mission to protect the forest and all its spirits and creatures while promoting a balance in peace and safety for humans and wildlife, with Eboshi’s vow to build a better town without harming the environment any longer.

In an interview with the Tokuma Shoten in 1997, Miyazaki describes the message behind the movie: “We can’t coexist with nature as long as we live humbly, and we destroy it because we become greedy. When we recognize that even living humbly destroys nature, we don't know what to do(...)Unless we put ourselves in a place where we don't know what to do and start from there, we cannot think about environmental issues or issues concerning nature. It leads to the idea that the world is not just for humans, but for all life, and humans are allowed to live in a corner of the world.”

Princess Mononoke serves as a fantastical yet pragmatic echo of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals of Decent Work and Economic Growth, Reduced Inequalities and Life on Land. Fantasy films such as these definitely bring a kind of despair by foreseeing the fictional future, but also bring a new and optimistic view on what we could do with technology, or at least how we could steer it in the right direction to achieve environmental salvation.

Learn more about Studio Ghibli films here.