Columnists and talking heads on both the left and right were inflamed when Turner Classic Movies (TCM) announced a new show entitled, Reframing Classics, which was meant to acknowledge problematic films of the past such as Gone With The Wind.

However, there are films produced much more recently that deal with the same issues in ways just as wrongheaded and controversial - only their impact hasn’t quite been felt yet.

It is the same spirit that TCM adopted to contested classics that can now be applied to films like Arne Glimcher’s Just Cause. Only, unlike TCM, they don’t necessarily have to be considered as classical pieces of art nor be acknowledged to align with a particular United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG), such as Reduced Inequalities.

The ways Just Cause misses the mark, artistically and otherwise, begins with the opening scene. Professor Paul Armstrong (Sean Connery) is holding a debate in the halls of Harvard about the death penalty with another man, played by journalist George Plimpton.

There’s no reason for this cameo, nor is there any explanation for it by other critics. Plimpton was never known for being outspoken for or against the death penalty, his politics dictate that he’d likely be in opposition. This scene is as random as it feels.

Armstrong argues that the death penalty is unfairly and unjustly used against African Americans, and soon after is approached by the mother of Bobby Earl Ferguson (Blair Underwood), currently on death row for the brutal rape and murder of a young white girl. Armstrong reluctantly takes the case, and it’s not long before he learns of the corrupt sheriff (Lawrence Fishburne) who beat a confession out of Ferguson eight years prior.

The stereotypes at work for black people are some of the most obvious, and common of the 90s, and they’re strangely always at work in legal thrillers. Popular American novelist, Josh Grisham, in particular, was a big fan of the poor, black, overcrowded family in the South - the patron clad only in blue overalls and covered in sweat.

The South of the United States is hot, as is universally known. However, this is also a common shorthand for poverty and a lack of education. The difference with Grisham films is that he’s often on their side - in a very 90s way. Here, the black characters are either cops abusing their power or accused murderers and rapists.

Further evidence points to another death row inmate (Ed Harris), and it’s not long before Ferguson is looking at early release.

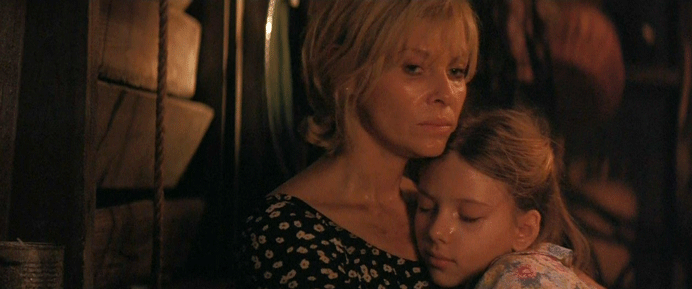

There’s really no way to discuss the problems at work in Just Cause without some major spoilers. Ferguson is released (the viewer never spends more than two minutes inside a courtroom), but Armstrong learns that his wife (Kate Capshaw) had served as a prosecutor on a previous rape charge that was not successful against Ferguson. Not only did he rape and kill the girl he was accused of, but Ferguson also intends to kidnap and kill Armstrong’s wife and daughter (a very young Scarlett Johansson).

To clarify; Armstrong is a man who dedicates his life fighting for justice for black people he thinks are wrongfully imprisoned. So the only conclusion one can draw from this instance is that his entire premise is a fallacy. Connery’s only potential arc is to become a racist. All black people in jail should be there, according to Just Cause.

There are movies where a twist like this could work, where it’s not mired in such obvious racial discrimination. Just Cause was a legal thriller, after all, one of the most bankable subgenres of the mid-90s.

Films that got mentioned alongside Just Cause would be A Time To Kill, Guilty As Sin, The Client and A Few Good Men. Not all of them were particularly good films, but they were selling as the “movies for grown-ups” of the decade (a concept that has died as well).

The twist also coincided with a historical event that is still reverberating through Washington. Just a year before its release, the infamous Clinton Crime Bill had passed the Senate. Three hundred and sixty-five pages of legislation added more cops on the streets and furthered the unnecessarily punitive crime laws against black people that had started with Reagan’s Anti-Drug Abuse Acts.

Part of the reason Glimcher’s film has largely been forgotten is that it wasn’t a success. It is quite understandable why. This is a courtroom thriller without a courtroom. Critics rightfully lambasted it, but shockingly no one ever mentioned in reviews at the time how egregiously racist it was.

Most of the conversation was focused on plot twists and lines like Connery’s, “If that’s a confession, then my a** is a banjo!” Not on the fact that it was promoting an agenda with harmful consequences on an entire community. However, this film speaks to the decade and it is something we can learn from. Just Cause got a pass at the time because we didn’t see a very obvious problem that’s apparent today.

It is hard to think of a film promoting less sustainable values. If anything, its biracial cast is something to admire, but Fishburne and Underwood may have been better off if they were stock characters. It’d be less offensive to have them as the standard sidekicks or bumbling comic reliefs than brutal killers.

Glimcher had previously had a hit with his movie The Mambo Kings, which was lauded for how vibrant and alive it made the music feel. Just Cause is the antithesis of that film, flat and antiseptic, worth watching for its amazingly offensive politics or a few Connery laughs.

It’s no wonder Hillary Clinton, former United States Secretary of State, in a New Hampshire speech given a year after Just Cause’s release, used the term, “Superpredator”. Just Cause provided and encouraged an environment for such language. It is Superpredator: The Movie.

Though Just Cause was 16 years ago, the problems of exploitation it focused on are still with us today. Fortunately, there’s much you can do yourself to combat it. Please visit aclu.org or innocenceproject.org to see how you can be involved in their community projects and initiatives.