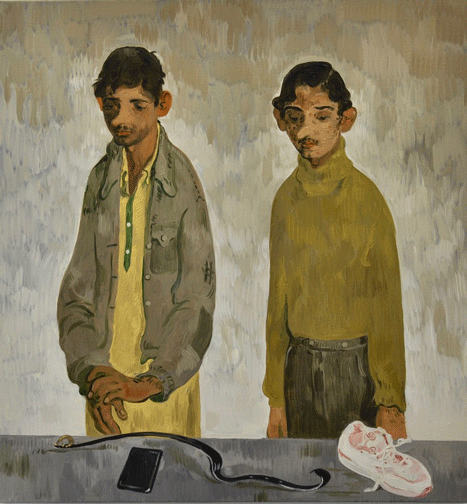

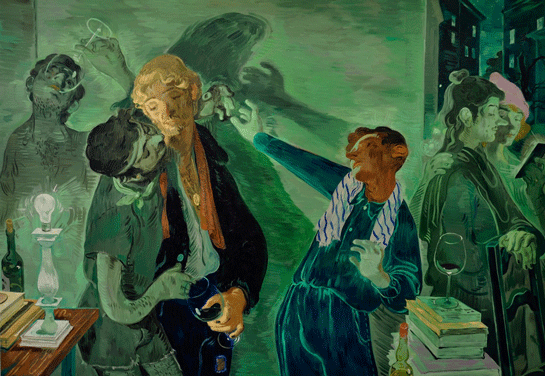

Salman’s artwork showcases queer diasporic communities: brown men embracing each other, a mehfil (party) scene with brown men playing traditional south asian musical instruments, dejected-looking brown men standing with their luggage on display at the immigrant counter.

His artwork examines joyous gatherings of people from various communities embracing and singing, friends doing each other’s makeup. His art, more importantly, also highlights the loneliness and alienation prominent in the immigrant community as they navigate their way through a new system of life. A few paintings of his deal with policing of brown queer identities.

His paintings carefully depict the differences between the private and public lives of the queer diaspora.

Salman’s artwork tackles the UN’s Reduce Inequalities, and Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions Sustainable Development Goals. The anxiety of identity and belonging are central in his work. He examines the racialization of subjects, juxtaposing brown queer men in white spaces; creating a parallel between his own upbringing in a strict conservative household and his life in the US.

Situating different lifestyles in every painting, Salman seems to be advocating for institutions that allow for collective and holistic growth of people.

While talking about Salman’s painting, curatorial assistant Ambika Trasi says, “Painting his characters as though haloed in divine light or as well-dressed dandies, his work pays homage to 'chosen family' and the importance it has for the communities that he references.”

His paintings bridge the physical and metaphorical gap between his two homes: New York and Lahore.

Salman explains, “For me, the in-between spaces are metaphorical/allegorical spaces of bureaucracy and suspicion. [...] They are certainly rooted in the diasporic experience and in the idea that you may not belong anywhere while thinking that you belong in multiple places.

“To present yourself on the cusp of another world is to be seen. It’s a powerful and lasting experience that doesn’t end with the encounters in these transitory spaces.”

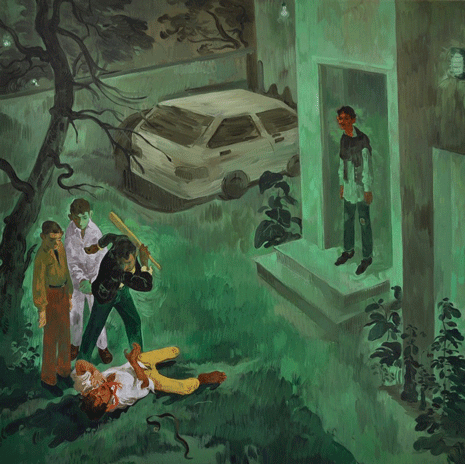

Emphasizing the prominence of green shades in his artwork, Salman says, “I chose green for aesthetic reasons. There is something nocturnal about it, like night vision. It’s inviting and glamorous, but it has connotations of poisonous gases and potions. But most importantly, I like that it’s not a sentimental colour.”

In an interview with Alina Cohen, Salman explains how, for him, the green hue “relates less to the absinthe in old Parisian cafés than to the aura of Slytherin.” Salman however, Alina remarks, “identifies as Ravenclaw or Hufflepuff.”

Avoiding sentimentalism and nostalgia seems to be a crucial part of Salman’s work. He places his characters in the real world and scenes that are not particularly pleasant to encounter, especially in Ambush II and The Beating. Surveillance also is a key component in Salman’s work.

The miniature style paintings, the initial collection inspired by 17th century South Asian, especially Mughal, and classical European style, are often painted with thick strokes. They are too big to provide a blended shade of colours, and rather, as Roberta Smith describes it, “remain staunchly visible and comforting, conveying crucial details and capturing the telling facial expressions at which the artist excels.”

Departing from life-like figures, Salman’s painted characters are “tinged” with stylistic elements of “illustrations and fairy tales”.

“He thought of wooden dolls, Pinocchio, and stories of innocent children. It excited Toor to distort his new figures, which featured a cobbled-together, patchwork essence,” writes Alina Cohen in an article in Artsy.

Salman’s childhood paintings were mainly images of women, sometimes copying the models from his mother’s fashion magazine.

Salman says, “I was drawn to the lines of their makeup, the graceful lines of their eyes and their bodies. I was a sissy boy, often bullied at school and policed everywhere else. The drawings were a way of inhabiting and feeling the empowerment of these women that I drew.”

In his more recent paintings, fashion turned into a tool of empowerment and critique. In Immigration Men, for example, the men’s ‘kurta,’ the long shirts, are more loose-fitting than they are intended to be. Their clothing matched the darb environment of the immigration office.

Emphasizing the choice of the clothes in Immigration Men, Salman says, “Fashion is a tool of [...] describing poverty or humiliation on someone foreign.”

Visit Salman Toor’s website to check out more of his miniatures.To support BIPOC artists, visit Allies in Art.