Western society commonly brands the archetypal doll’s houses or dollhouses as feminine objects. Tried as one of many gendered toys given to youth in early childhood, these intricate dioramas of suburban homes are fictitious miniature objects designed to insight desire and aspiration. Dollhouses inspire young children to dream about what could, one day, be. Through playful interaction with these structures, children recognize and manifest systematic, capitalist ideals: striving to own a grand house, have a family, and care for a home. Be it a plastic Barbie’s Dreamhouse or a wooden model home filled with handcrafted trinkets passed down through generations, dollhouse structures have fantastical natures. Yet, fantasy is not always affirmative; a dollhouse’s symbolism is fuelled by underlying histories imbued with restrictive societal tenets, making it an interesting motif to investigate.

Yale School of Art graduate, Sula Bermúdez-Silverman is a multidisciplinary artist currently living in Los Angeles. California African American Museum, the host of the artist’s recent solo-exhibition Neither Fish, Flesh, nor Fowl, communicates that within her practice “Bermúdez-Silverman mines her personal and familial histories as a woman of Afro-Puerto Rican and Jewish descent,” manufacturing novel sculptures of objects from organic materials like sugar, salt, and her hair. She uses materials, which reference her mixed cultural and racial heritage, to distort the universally symbolic narratives of quotidian objects like quilts and dollhouses and practices such as yarn-making and embroidery. In her series, DNA Portraits, the artist transfigures “genetic data,” sourced from family members’ ethnic DNA screenings, “into colorful,” embroidered, “pie charts,” to visually “convey the complexities of identification, in particular the role and interplay of religion, race, ethnicity, and nationality.”

Bermúdez-Silverman inspects societal systems, structures, and histories intertwined with Eurocentric capitalism to question and recognize how economic, racial, and gendered systems of power have traditionally and categorically defined Western notions of identity and understanding. With her practice, she bears the importance of recognizing intersectionality.

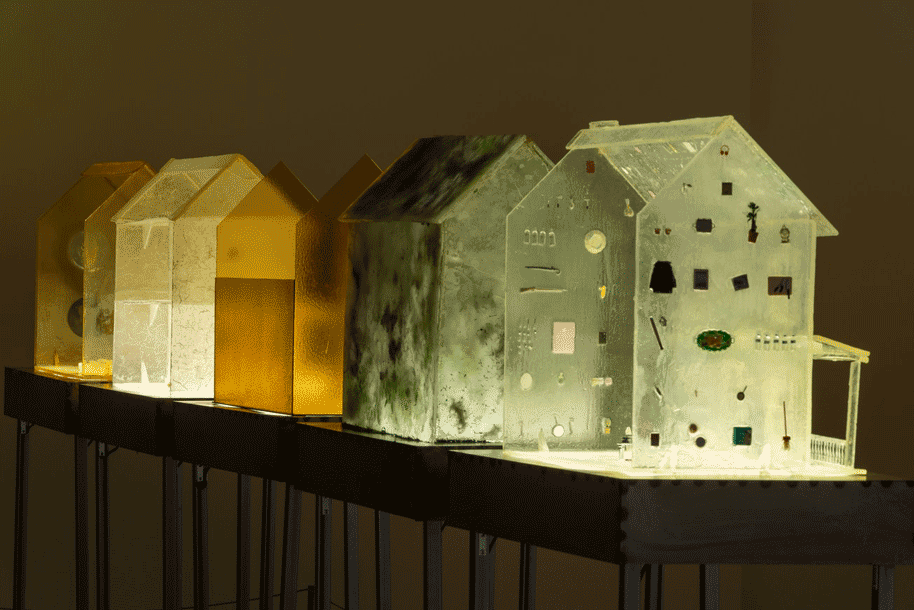

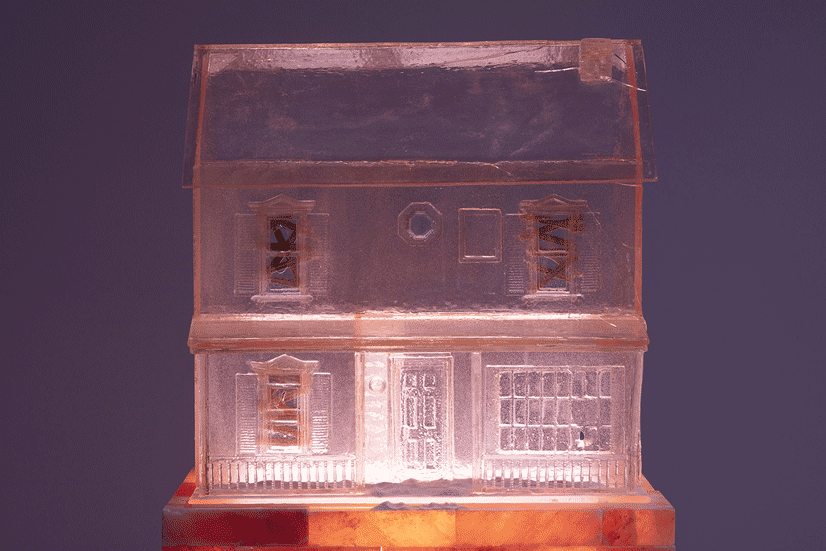

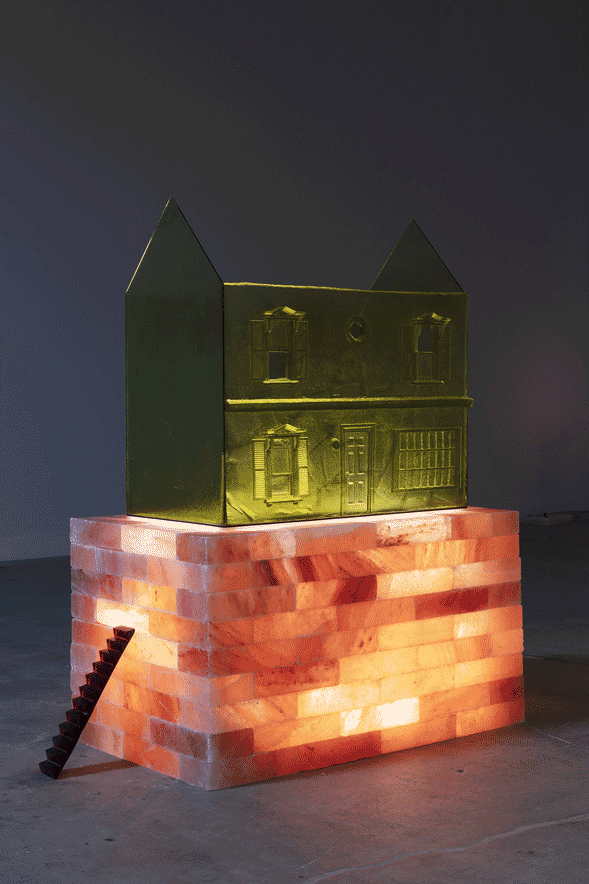

The figure of a dollhouse is prominent motif in Bermúdez-Silverman’s newest work on display at CAAM, and in the recent exhibit, Sighs and Leers and Crocodile Tears at Murmurs Gallery in LA. Through a primary process of melting, pouring, molding, and soldering sugar, the artist architects variations of the same translucent house, using the dollhouse which was made for her in early childhood “as a blueprint” for the sculptures.

With ghostly clear frames, these structures exude an overt fragility. They are softly illuminated from within to exaggerate their eerie, mystical auras. As Allison Conner remarks, the sugar sculptures feel like “uncanny props from forgotten movies.” Recent examples of the houses, such as Repository I: Mother and Repository II: Dead Ringer, stand on pedestals made from blocks of salt and glass, which similar to sugar, are “rarified products of colonialism.” Purposefully drawing on aesthetics of horror and monster lore, while utilizing historically colonial materials, the sculptures communicate “how forces like capitalism and colonialism inflict horror on everyday people.”

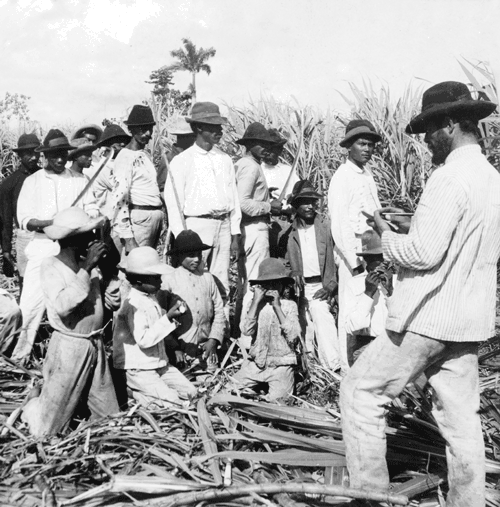

Contextualizing her use of sugar, Bermúdez-Silverman articulates, “I started working with sugar as a material, or thinking about sugar as material, learning that my ancestors worked on sugarcane plantations in Puerto Rico.” Before the 18th century, sugar was a rare commodity in European countries––an ingredient with limited accessibility and afforded only by the privileged and wealthy. The European colonization, exploitation, and implementation of plantation systems on Caribbean land, which was “well suited for sugarcane agriculture and sugar factories,” transformed sugar to a highly desirable and affordable commodity. At the expense of enforcing slavery and labour on Caribbean peoples, by the 19th century, sugar was a necessity in most European households and still remains a staple in homes worldwide.

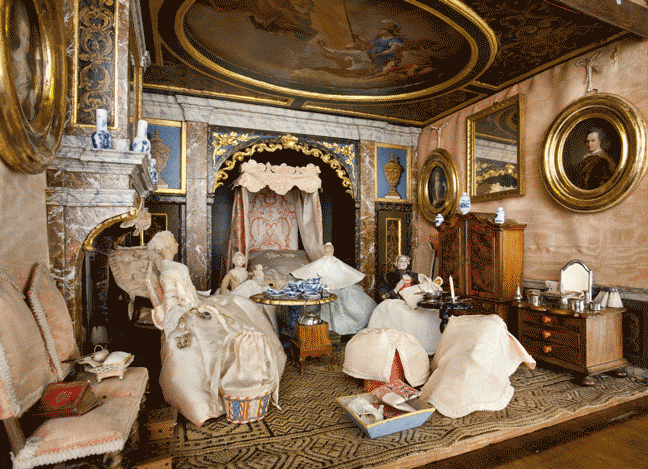

For Bermúdez-Silverman, sugar is a compelling artistic material because it’s a commodity tied to the standardization of capitalism. Moreover, as objects, both sugar and dollhouses have historically and symbolically evolved––once items exclusive to elite classes, these objects are now universal household items. In the 18th century, dollhouses were not recognized as toys, rather “the province of upper-class women who dedicated untold hours and great sums of money to creating alternate domestic spaces in miniature.” Made for wealthy young women, early grand dollhouses, provided daughters of elite families, “with an instructional forum for the organization of household space, and allowing them mechanisms to role-play their responsibilities as the mistress of a patrician household.”

Art historian Deborah Varat articulates, “There is something ironic about the idea of an upper-class woman playing at cooking, arranging pots in a kitchen, and setting up for tea when in reality women of this station would have done none of those things.” Women of this economic stature, while not having to actually care for a household and instead burdening their servants, still embodied these gendered everyday roles through imagination and creation. This is similar to how normative society guides young children to perform adult-like tasks under the guise of “play” to inevitably mimic the actions of their caretakers, or to “prepare” for their predetermined future tasks as a parent or homemaker. Varat says dollhouses “were designed as showcases of domesticity; their scale garnered notice, their grandeur demanded admiration.” No longer an item just for the elite, the dollhouse universally evokes the ideals of the nuclear family and cisgender feminine figure.

Bermúdez-Silverman makes dollhouses––not for play or (capitalist) dreaming––but to reimagine their everyday value and expose the freaky systems of gendered, racial, and elitist power that quietly live on in everyday consumerist objects; the items with forgotten and under-realized monstrous histories.