Found Object art dates back around 3 million years ago, when a crude face-shaped stone from the Stone Age was discovered by archeologists in a cave in an area it did not originate from. Millions of years later in the 1900s, Marcel Duchamp and the Dada movement popularized Found Object art as a legitimate art form.

The once controversial movement is named after the French objet trouvé, which can be literally translated to “found object.” The meaning behind this name refers to the use of recognizable objects usually not considered to be art materials, which are modified by the artist and placed into an art-related context.

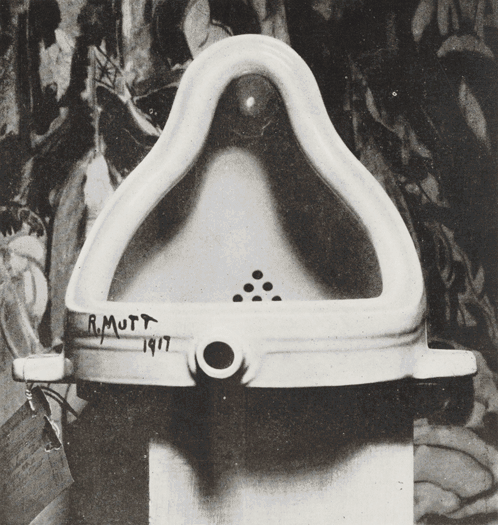

In 1914, Marcel Duchamp began his Readymades series as a response to contemporary visual art. After studying Impressionism and Cubism in France, he concluded that painting is for the eyes, whereas art should be for the mind. His series, first displayed publicly in New York City, consisted of unaltered ordinary objects, which were largely rejected by art juries and the public, and not considered art by any definition at the time. Through the display of a urinal titled Fountain, Duchamp challenged the notion of what makes art and his concept of Readymades remained fluid; "The curious thing about the readymade is that I've never been able to arrive at a definition or explanation that fully satisfies me. I was interested in ideas—not merely in visual products.”

Duchamp’s famous Fountain, a urinal purchased from a hardware store, with the signature “R. Mutt,” is known as a triumph in artistic experimentation of the 20th Century. Duchamp submitted Fountain to the Society of Independent Artists, which accepted it merely due to their policy that all pieces submitted by artists who pay the entry fee cannot be rejected. However, they excluded Fountain from the society’s show.

As a reaction to Duchamp’s exclusion, the New York Dada art movement flourished. The Dada movement, which began a few years earlier as a response to the First World War, involved artists who rejected traditional values and aesthetics in art. Instead, their art focused on irrationality and expression, while intentionally defying the bourgeois culture. The movement proposed subtle mockery and existential despair in an effort to mediate postwar trauma and an exhausted Eurocentric art cannon. Dada was born in writer Hugo Ball’s satirical nightclub in Zurich called Cabaret Voltaire. In 1916, Ball read aloud the Dada Manifesto at his club and thus initiated the Dada movement.

“Dada is a new tendency in art. One can tell this from the fact that until now nobody knew anything about it, and tomorrow everyone in Zurich will be talking about it… How can one get rid of everything that smacks of journalism, worms, everything nice and right, blinkered, moralistic, Europeanised, enervated? By saying dada.”

- Hugo Ball, Dada Manifesto

The Dada Era did not last long, dwindling by the 1920s as a result of the public’s disgust. Though this disgust only encouraged these alternative artists, many of whom went on to create more prominent movements in Found Object art.

While Duchamp made less than twenty Readymades in his lifetime, other artists contributed to the art form as well. While living in New York, Man Ray abandoned traditional art to pursue a Dada-infused platform. From 1918 to 1920, Man Ray experimented with Readymades, creating obscene sculptures from ordinary objects, such as The Gift, a flatiron with a line of tacks glued down the middle. The materials in Man Ray’s Found Object pieces included a sewing machine, string, horsehair, carved wood, glass plates, a motor, and a mannequin. As with the Found Object movement itself, Man Ray challenged the conception of art and became an antagonist to traditional aesthetics.

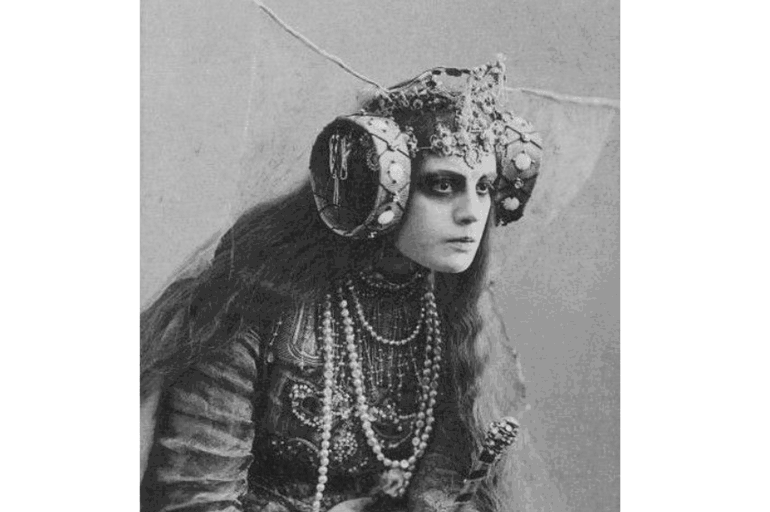

Another artist, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, used Found Object art as a daily performance. The bohemian feminist used fashion as her artistic outlet. She adorned her clothing with spoons, tin cans, and street debris. Her body was her medium, challenging consumerism and the social constraints on women. While considered eccentric, Baroness Elsa believed “every artist is crazy with respect to ordinary life.”

After the creation of Duchamp’s Readymades and many artists’ influences, the Dada movement morphed and merged with Surrealism. Surrealism aimed to stimulate the unconscious mind through juxtaposed imagery, crafting unnerving and strange artwork. The name itself comes from the merging of dreams and reality, known as a super-reality.

A jack of all trades, Salvador Dali used many mediums to establish his Surrealist mastermind, including Found Object sculptures. As another artist who wanted to re-conceive the meaning of art, Dali used bizarre objects with underlying connotations. For example, one of his favourite analogies was food and sex, which was showcased by his suggestive Lobster Telephone. The playful and peculiar combination of unassociated objects was a constant in Surrealism, urging viewers to expose their subconscious desires.

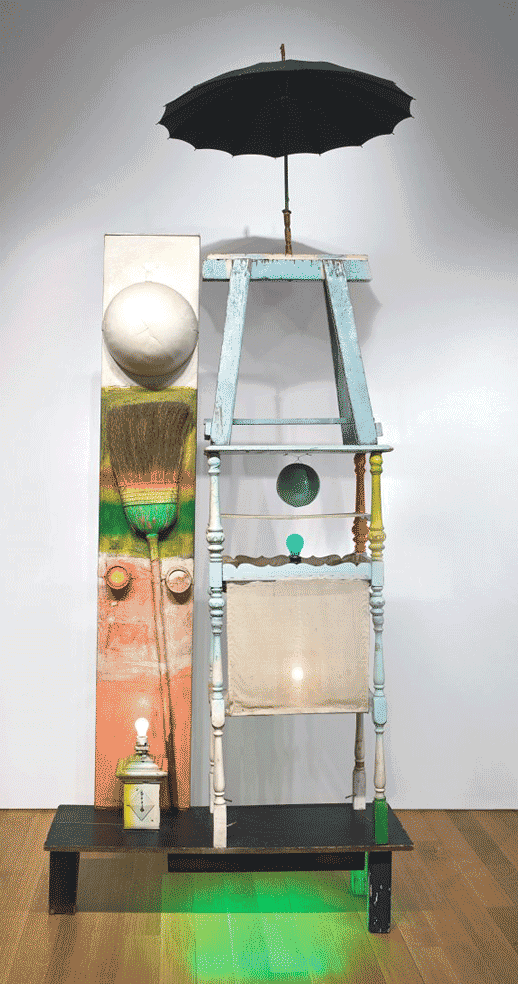

In 1936, The Zabriskie Gallery in New York on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 57th Street began to exhibit Surrealist objects. Found Object art slowly shifted from Readymades to Assemblage. A popular Dadaist who kept the artistic rebellion alive was Kurt Schwitters. He made collages from discarded and short-lived materials, such as bus tickets and labels. Sometimes Schwitters would incorporate everyday objects into his pieces to create Assemblages, essentially 3D collages.

The 1960s continued to see Found Object art in other movements, including Pop Art. A key contributor to the movement was Robert Rauschenberg, who collected discarded objects from the streets of New York and added them to his artwork. He used the element of surprise by incorporating these items into a new setting. He claimed that “the object itself was changed by its context and therefore it became a new thing.” Similar to Duchamp and Dadaism, Rauschenberg wanted his audience to challenge their conception and definition of art.

Since the 1980s, Commodity Sculpture and Trash Art have borrowed principles from the Found Object art movement. Commodity Sculpture uses a variety of mass-produced products arranged to create a sculpture. Trash Art uses miscellaneous unwanted objects to fashion something new. Both speak to a new consciousness toward sustainability and the environment.

Jeff Koons, a prominent figure in today’s Found Object art scene, exhibited a series titled “The New.” The series included a Found Art sculpture of brand new Vacuums: New Hoover Convertibles, Green, Red, Brown, New Shelton Wet/Dry 10 Gallon Displaced Doubledecker. Koons wanted the exhibition to comment on society’s obsession with newness, cleanliness, and consumption. Koons explained, “I don’t seek to make consumer icons, but to decode why and how consumer objects are glorified.”

Found Object art has pushed the boundaries of art for decades. Artists who abide by the principles of the movement believe that art is strongly related to context. If Duchamp’s urinal was placed in a bathroom, would it still be the famous Fountain? Because the piece was taken out of its intended place and repurposed, Duchamp would argue that this makes it art. Similar to Dadaism, Found Object rejects traditional views of art and challenges its audience to consider intentionality. This theme can also be found in Surrealism and Pop Art, both of which lift unconscious questions to the surface. While Surrealism focused on juxtaposition and altered reality, Pop Art used mass-consumed images and objects. Both movements longed for their viewers to question – whether it be what art is or who we are.

Today, Found Object art expresses sustainability and examines consumerism. For over a century, people have found this art movement bizarre and unusual. However, now more than ever, using everyday objects, debris, street waste, and mass-produced substances to construct art forces people to deconstruct their connection to ‘things.’ Audiences may not always understand what Found Object art means, but hopefully they can challenge their relationships with these objects. Perhaps Found Object art is simply about this relationship, between viewer and object. Found Object art in the modern world both encourages sustainable practices while disconnecting artists and viewers to the material hold of consumerism.