The Age of Enlightenment marked the beginning of Flora Danica. Striving to understand nature through knowledge, King Frederik V of Denmark commanded the compiling of the Kingdom’s wild plants for reference and ongoing study in what has been called the world’s largest public education program. King Frederik was drawing from the longstanding tradition of gathering descriptions, legends, uses, and dangers involving native plants. Due to the emphasis on classifying and identifying flora in the 18th century, this project focused on spreading visual information and local knowledge in addition to the aim of popularizing botany. The ambitious project intended to include a series of texts along with the engraved plates to further disseminate knowledge about the uses of the plants as a type of encyclopedia. As a result of the comprehensive scope of the project, however, the text was never produced.

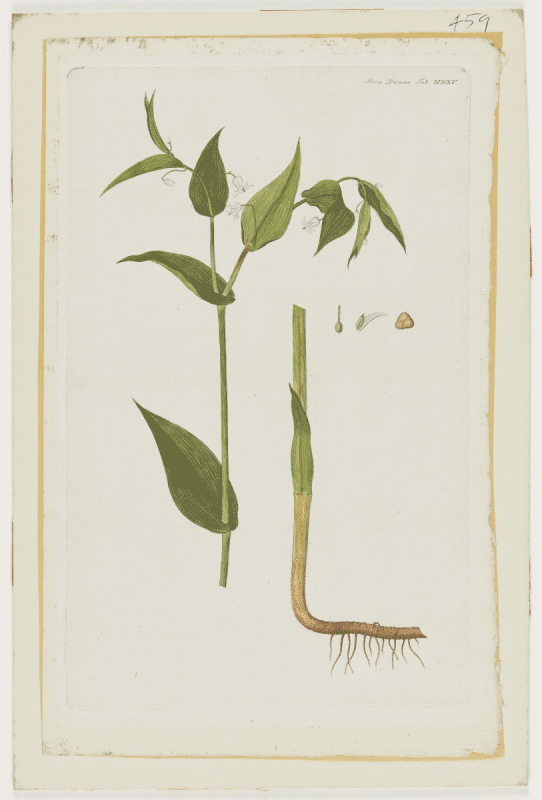

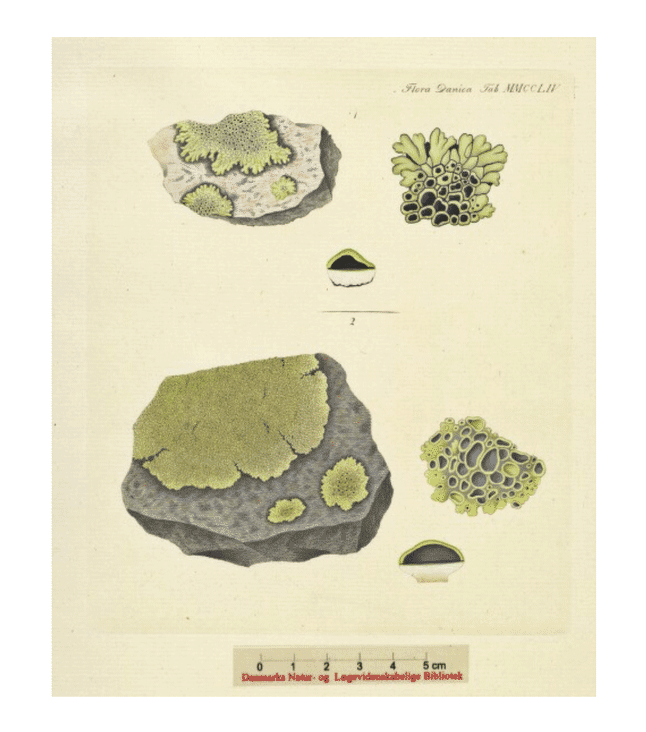

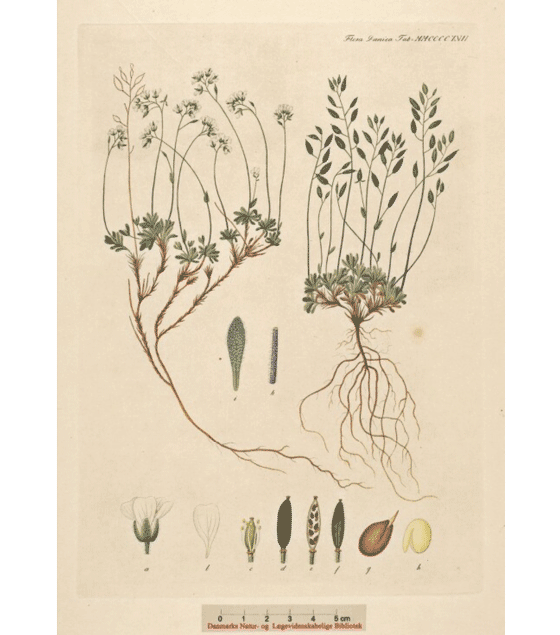

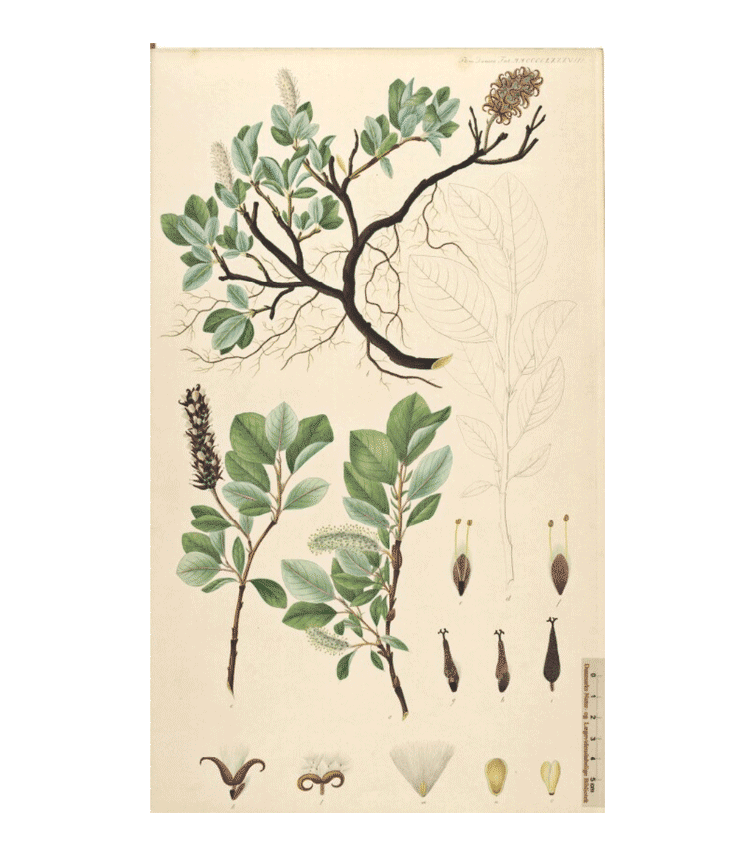

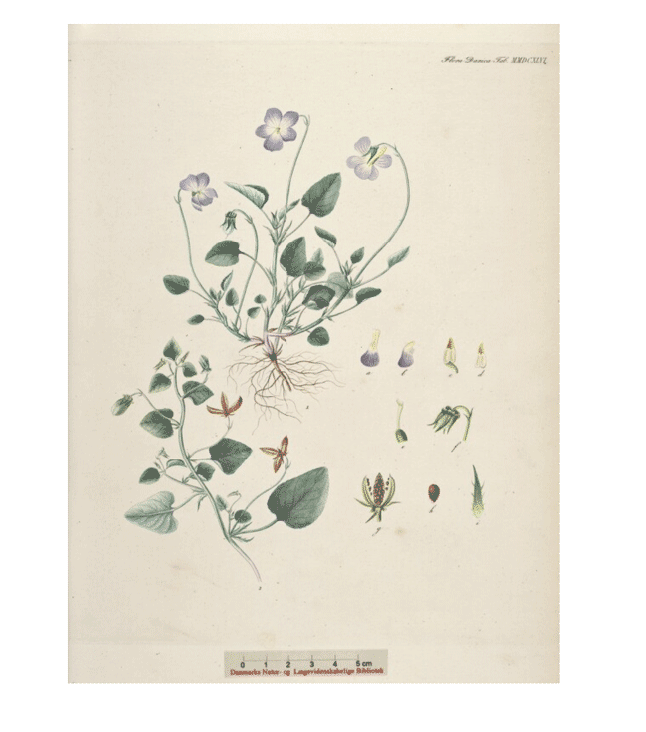

Sponsored by the Royal Court of Denmark, thousands of individuals, including artists, engravers, botanists, and zoologists, had the opportunity to work on this project from 1761-1883. Georg Christian Oeder planned and started the Flora Danica publication, and over 122 years, the collection grew to be impressive in both its scale and in its artistry. After 123 years of production, the 51 different parts of Flora Danica and many additions display a new world of botany and a window into ecological history. A total of 3240 engravings are available after these efforts and referring to plants drawn and coloured from life, engravers worked tirelessly providing information about all of the parts of the plants. While there were thousands of engravings, each piece followed a set of rules, namely that plants be shown alone on each page. Of course, there are a few exceptions–in one case, four types of lichen are displayed on a single page for comparison. The plants were also depicted life-size, with large plants shown in a smaller size with life-size details.

Throughout history, specific plants faded in and out of interest as politics changed. As the project began, Denmark, Norway, and off-shore affiliates of Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands were all involved. With that said, when Denmark lost territories later in the century, plants native to those regions were omitted from the publication. In later decades, the publication eventually became more holistic in its approach, including all plants once again. What is particularly interesting about Flora Danica is that only plants grown in the wild were to be included. Specifically, this meant that plants cultivated by humans were not to be found in the works. Wild roses and wild grasses may appear, but those bred by humans, would not be seen.

Flora Danica plates, which are now at the Botanical Museum in Copenhagen, were made on copper. The copper engraving technique, developed in the early 15th Century involves covering a polished copper plate with a thin layer of wax, upon which the plants could be drawn. To ensure the proper arrangement of the plant motif, it was drawn as a mirror-image. After engraving, the plate was inked and dried allowing the colour to only linger in the grooves. Single-coloured prints were then able to be made in the press. To ensure even distribution of Flora Danica throughout the kingdom numerous copies were given to the bishops, who then distributed them to clergymen and other educated individuals

Hand-coloured versions of the work required individual attention and were produced far less often due to the cost in comparison to their black and white outline counterparts. Children and women who were hired to hand-colour these works to avoid hiring expensive guild workers. Copies of these works are already scarce, and the labor required in their production means that few viable copies in good shape exist today.

Flora Danica became the source material for a ceramic line in 1790 commissioned by King Frederik. Intended as a present to Catherine II she never received the gift and later died in 1796. The set of porcelain was created and hand coloured with replicated illustrations of the copper plates. In total, 1802 pieces of china were produced. Today about 1500 of these remain in the hands of the Royal Danish family.