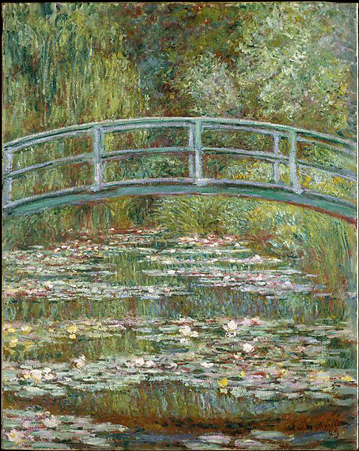

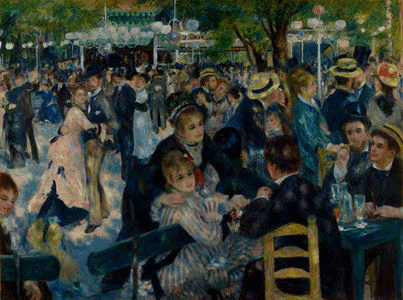

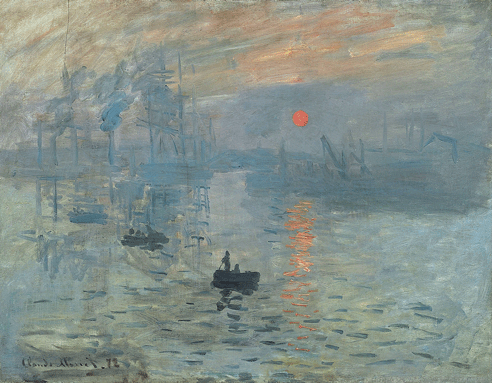

The rule of Impressionism is potent in Western culture. In addition to ushering in modernism, the French Impressionist movement dominates the Western concept of art and aesthetics. For good reason, too – Impressionist work is pleasing while maintaining subjective neutrality that appeals to everyone, creating the perfect symbol for digestible art. Monet, Renoir, and Sisley are icons in global arts and culture, easily recognizable figures in art history. Their early years are well catalogued, but a quick examination brings forth a lesser-known name: Frédéric Bazille. In their early years, Bazille was integral to the group, both financially and emotionally. So why has history failed to elevate him?

Bazille died in his prime. At the age of twenty-seven, Bazille would be killed in combat during the Franco-Prussian War, abruptly ending his blossoming career as a painter. Only four years later, his friends and colleagues would initiate the famous exhibition that rejected the Paris Salon’s approval and gave the Impressionists their name. Despite his relationship with the group, none of Bazille’s work would be displayed, relegating him to the historical background. For decades after, the void of history seemed to have swallowed up Bazille’s work and legacy. Luckily for the ambitious young Parisian, an Impressionist scholarly boom in the 1970s would help revive his work and jump-started a movement to remember the forgotten artist.

Bazille died in his prime. At the age of twenty-seven, Bazille would be killed in combat during the Franco-Prussian War, abruptly ending his blossoming career as a painter. Only four years later, his friends and colleagues would initiate the famous exhibition that rejected the Paris Salon’s approval and gave the Impressionists their name. Despite his relationship with the group, none of Bazille’s work would be displayed, relegating him to the historical background. For decades after, the void of history seemed to have swallowed up Bazille’s work and legacy. Luckily for the ambitious young Parisian, an Impressionist scholarly boom in the 1970s would help revive his work and jump-started a movement to remember the forgotten artist.

Nineteenth-century Paris adored letter writing, giving historians volumes of personal correspondence and insight into the life of the early Impressionists. Born in 1841 to a well-to-do French family in Montpelier, Bazille started down the path of a wealthy society gentleman, enrolling in medical school and moving to Paris at the age of twenty-one. Unfortunately, Bazille would prove to be a somewhat lacklustre student. In Paris, Bazille fell in love with art, attending multiple Salons and studios, eventually abandoning his mediocre medical career for the volatile world of painting. He met Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, Édouard Manet, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who shared his artistic ambition. As Bazille embraced painting wholeheartedly, the first historical argument against his artistic legacy mounted: he began to sponsor his fellow artists. Bazille supplied them with money, supplies, housing, a studio, and regularly purchased their paintings. His financial involvement worked against him posthumously, and earlier historians claimed his work was mediocre, and Monet simply humoured Bazille to bleed him dry.

This theory is easily contradicted, correspondence between Bazille and Monet does reveal some financial pressures and tension between the two, but it also captures the deep emotional and artistic connection they shared. Both young men desperately wanted Salon approval, striving to create a name for themselves. They shared living spaces, modelled, and confided in each other. Bazille, while ambitious, often lacked order and motivation, pushing Monet to go as far as to enforce a rigorous painting schedule for his friend. In turn, Bazille was privy to the vulnerable side of fiery and proud Monet. His 1865 work L'ambulance improvisée depicts an injured and frail Monet, alive with trust and tension between the two. Bazille also formed a close friendship with Renoir, the two betraying their mutual reliance and confidence in their correspondence. In 1867, Bazille painted Renoir in Portrait of Renoir, and Renoir responded with Frédéric Bazille at his Easel. The pictures are intimate despite their marks of amateurism. His financial support may have muddied history, but Bazille did indeed form close relationships with early Impressionists.

Bazille’s legacy faces a more significant challenge, however, because his early death left behind few works, all of which are marred by the mistakes of a young painter. During his lifetime, Bazille faced Salon rejection multiple times and continuously noted Monet’s artistic supremacy. He tackled similar questions of light, colour, and portrayal as his counterparts, making mistakes and questionable artistic choices. His colleagues and friends were also making mistakes, though, and the group was still painfully young, energetic but unseasoned. An early death meant, unlike Monet, historians have no proof that Bazille would progress artistically, only a notion of “what if.”

In recent decades, art historians have argued for the legacy of Bazille. His later work, Summer Scene (Bathers) and Young Woman with Peonies, exhibited artistic growth and gained attention during the Salon season. Bazille’s work exudes youthful ambition and joy, full of historically significant scenes. Summer Scene speaks to this environment, the bright colours and inconsistent lighting, creating a mirage-like collage of figures, full of tension and playful energy. Bazille was deeply insecure, and unlike his friends, never found satisfaction in later-life success. After his death, debates around his true function to the Impressionist movements prove indecisive, the lack of evidence seemingly insurmountable. However, as long as Impressionism stays relevant and continues to grow in popularity, scholarship and inference on Bazille’s history and fame will only grow. The latest major Bazille exhibition and retrospective in 2016 was celebratory, crowning Bazille, a creative genius whose life simply ended too soon. All things considered, I think Bazille would still be rather pleased.