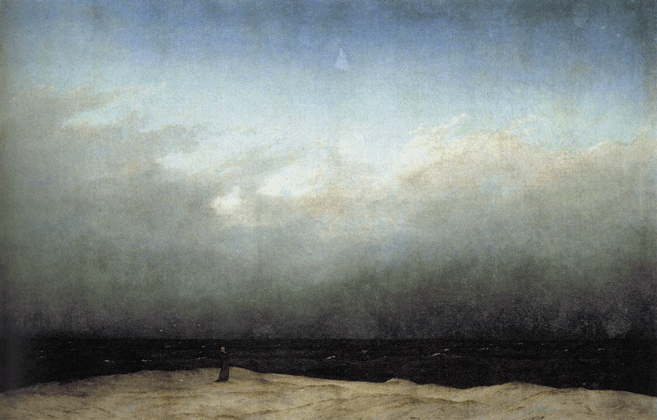

The rückenfigur, German for “figure from the back,” is a compositional device in painting originally used to convey the sense of longing, emotional isolation, and existential restlessness characteristic of the Romantic movement. The rückenfigur typically looks out onto a vast expanse of nature, a seemingly endless and often treacherous outer world that the darkened silhouette beholds as an endless opportunity of experience never to be fully realized. Therein lies the existential dilemma that haunted the Romantics: the inner world versus the outer world and the impossibility of fully knowing one’s place in the universe. Like the subject in Plato’s Cave, the rückenfigur contemplates the possibilities of experiencing the world first-hand, and wrestles with the meaning of perception. In using an often dark and indistinct impression of a person as seen from the back, artists created a metaphorical bridge for the viewer, a visual means of inserting oneself into the painting and thereby feeling closer to the scene itself. The rückenfigur shares their experience by proxy with the viewer, allowing for a simultaneous sense of unity and detachment as the figure stands in for the viewer within the painting.

The rückenfigur serves not only to place the viewer within the scene of the painting, but also to act as a means of understanding the grandiose scale of the painting’s environment. With the rückenfigur acting as a surrogate for the viewer, one is able to live vicariously through their experience of nature’s sublimity. The passive act of emotional transference from viewer to painted subject is yet an imperfect exchange; art historian Joseph Leo Koerner argues, “[I am] at the threshold where the scene opens up, but at the point of exclusion, where the world stands complete without me.” This feeling of empathy gained through supposing oneself into the place of the ambiguous figure is often noted as an unreliable method of delineating a relationship between the viewer and the scene of which they behold. The viewer is often presented with a sense of kinship with the rückenfigur, as if the figure itself were an open door or avatar from which to view the painted world; they are, however, simultaneously excluded from this world and reminded of the distance between oneself and the figure standing before them. This paradox creates a strain that perfectly captures the essence of the Romantic movement, whose practitioners favoured the subjectivity of emotion and psychological nuance as opposed to the staunch rigidity of many previous artistic movements in history.

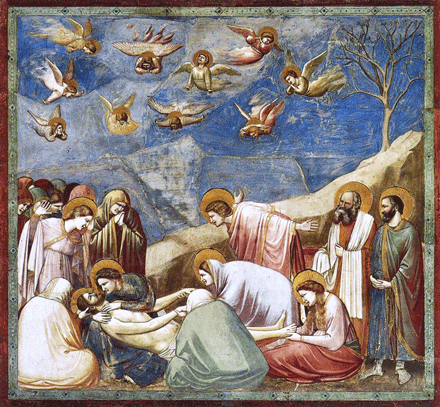

The motif of the rückenfigur can be seen in a formalistic application as early as the 14th century, as with Giotto di Bondone’s Lamentation of Christ (1300s) in which the artist depicts two figures with their backs to the viewer, though common use of the rückenfigur would not develop until centuries later. The figure as seen from behind and its use to connote emotional exploration and awe of nature’s boundlessness inextricably link the rückenfigur to the Romantic movement, and the artist most closely associated with the rückenfigur is Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), whose iconic painting Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818) has become the exemplar of Romantic aesthetics. The heroic archetype in nature (a staple of Romantic idealism) is signified by the triangular composition of the man standing on the cliff, of which he is the pinnacle; he stands confident and serene as he faces the elements and looks into the turbulent landscape before him. The use of sfumato to blur the focus of the distant mountains symbolizes the unknown future and implies that this man is a visionary: he gazes into the fog, willing to embrace the uncertainties of the natural world, alone and in a state of self-reflection.

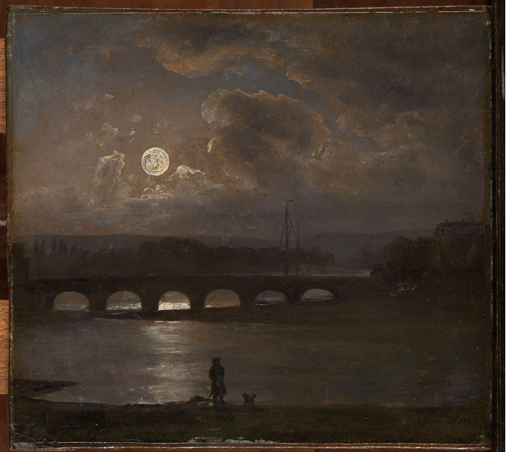

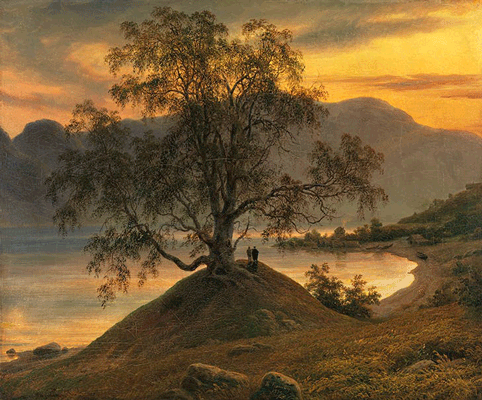

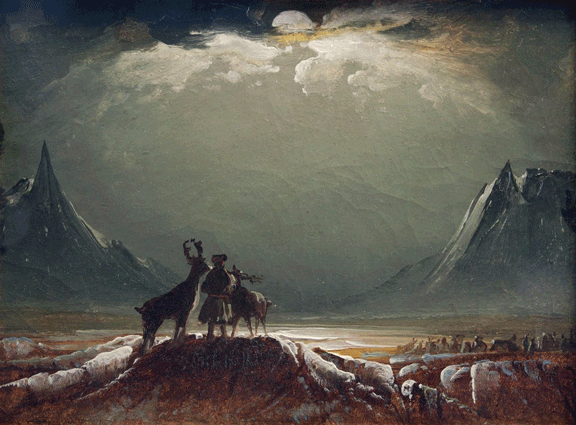

Prior to 1818, Friedrich painted several rückenfigur including Monk by the Sea (1810), a classic depiction of the sublime contemplation of God in nature, but it was Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog that spurred the rückenfigur into popular culture. Johan Christian Dahl (1788-1857) emulated Friedrich in Moonlit View of the River Elbe at Dresden (1826) and Mother and Child by the Sea (1830), as did Thomas Fearnley (1802-1842) with Old Birch Tree at the Sognefjord (1839), and Peder Balke (1804-1887) with Landscape from Finnmark with Sami and Reindeer (1850), all adhering to the Romantic reverence of nature. The extreme popularity of the heroic Romantic landscape painting fell out of fashion, however, towards the turn of the century, but the melancholy and existential qualities of the rückenfigur adapted into a post-industrialized world.

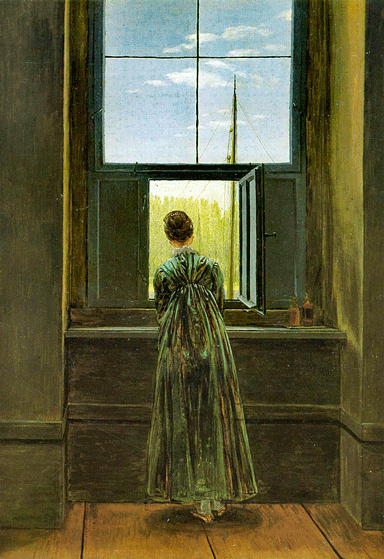

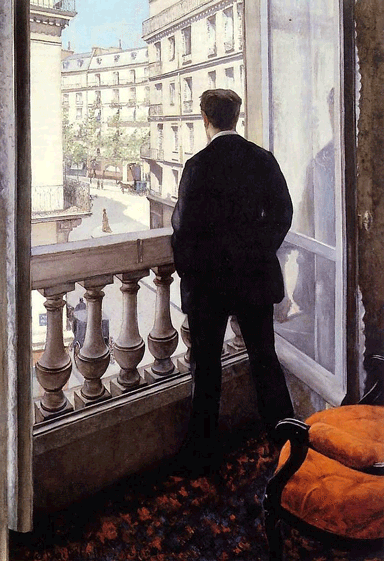

The portrayal of the contemplative figure against the backdrop of a vast natural space evolved into the image of a pensive figure looking out into the city, indicating the sense of isolation despite the abundance of people nearby. Friedrich adapted his outdoor setting to the interior with Woman at a Window (1822), a painting that likely influenced Gustave Caillebotte (1848-1894), whose Young Man at the Window (1876) took the leisurely tone of his popular flaneur paintings and added the sense of longing characteristic of the rückenfigur. Likewise, in keeping with a more sedate interpretation of the once brazen and awestruck figure, Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864-1916) countered the heroic posturing of the typical subject with Young Woman from Behind (1904), the haunting image of a darkly clothed woman, presumably a staff member, working on daily chores in a home. The figure, in this case, connotes the idea of a person trapped – unlike the traditional rückenfigur situated in the great outdoors looking into the endlessness of the natural world, the woman in this painting remains inside, her view is myopic as she faces the physical limits of the constructed world around her.

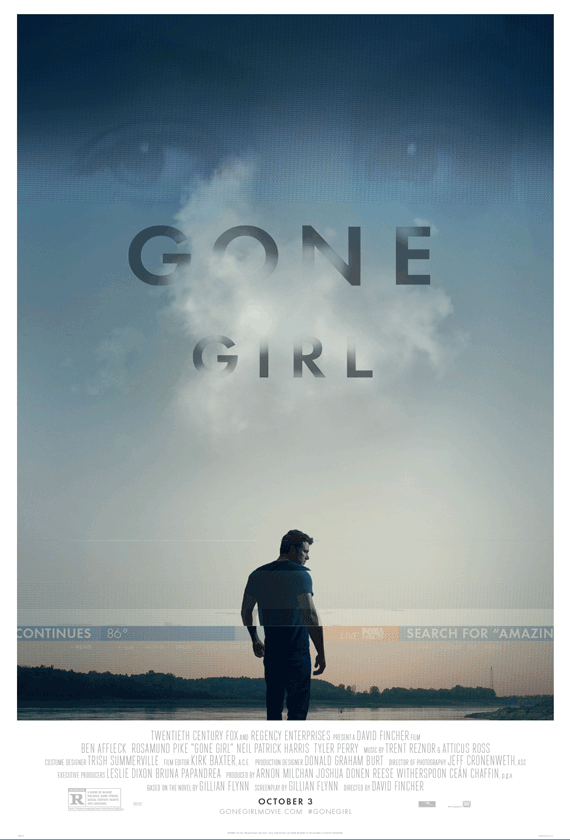

From Romantic wanderlust to gloomy post-industrialism, the rückenfigur would soon find itself reimagined again, this time as the figural gateway into whatever world the artist saw fit. Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009) created a reverse-Romantic psychological landscape in Christina’s World (1948), depicting a young woman in the unsettlingly open outdoors as she gazes back towards the safety of the distant farmhouse. Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) aimed to convey through the rückenfigur the joys of familial love by capturing the moment of a traveller’s return home with Homecoming Marine (1945) and Christmas Homecoming (1948), and popular culture in the form of advertising, film, and social media imagery has adopted the rückenfigur for its capacity to evoke a sense of identification from the viewer.

The appeal of the rückenfigur, despite changes in its surroundings, has remained constant since its conception in the early 19th century. Though the motif is omnipresent in popular culture and therefore seemingly timeless, the visual language as with nearly any artistic standards of representation has traceable roots in history and a cultural background through which it can be interpreted. Through variations in context, the meaning and reception of the image has altered, but regardless of the variations on intent, the indelible use of the rückenfigur as the viewers’ personal manifestation solidifies it as a universal image across all forms of visual media.