Before Michelangelo was a world-renowned artist, he was an expert art forger.

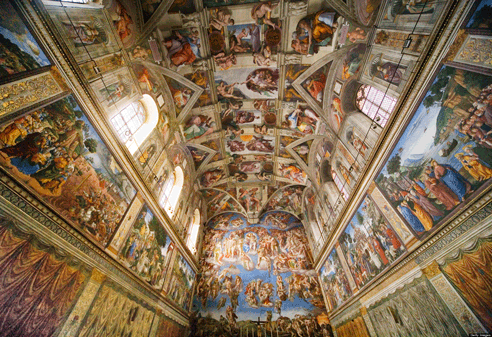

Born on March 6th, 1475 in the city of Caprese, Michelangelo Buonarroti was a minor noble whose family had long lost its patrimony and status. Early on, Michelangelo’s father realized that his son had no interest in the family’s financial ventures. At thirteen, Michelangelo was an apprentice to the city’s most prominent painter, Domenico Ghirlandaio. Here, the young artist was exposed to the technique of fresco, a type of mural technique where watercolors are painted on freshly-laid plaster, which he would use years later while painting the Sistine Chapel.

Michelangelo spent three years in Ghirlandaio’s service before Lorenzo de Medici, ruler of Florence and well-known patron of the arts, recognized his talents. Lorenzo took the young boy under his wing and exposed Michelangelo to the rich culture of the Italian Renaissance. Michelangelo socialized with Florence’s elite: poets, musicians, scholars, and humanitarians. More importantly, Michelangelo’s close ties with Lorenzo gave him access to the Medici’s art collection, which was dominated by ancient Roman statuary.

While Michelangelo had talent and passion, he was not well-known. At 21, he was just another starving artist attempting to sell his work for a profit. And there was little demand for his work: collectors were more interested in acquiring authentic Roman statues, like the ones on display in the Medici gallery. Florence was fertile ground for forgery, and Michelangelo made a risky move that could have ended his career.

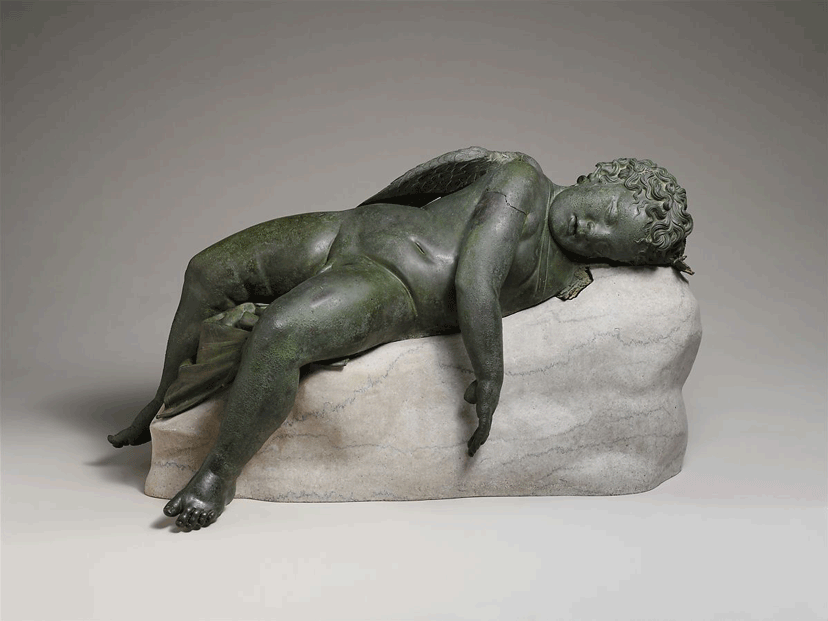

In 1496, Michelangelo carved the Sleeping Eros. The marble statue depicted a young Eros – the Greek god of love and passion – in slumber. Sleeping Eros was crafted to resemble the Roman statues which collectors coveted, but historians argue on how, exactly, it was aged. In one version of the story, Michelangelo artificially aged his statue using acidic earth. In another, art dealer Baldassari del Milanese buried the Sleeping Eros in his vineyard to damage the marble. Either way, the forgery was sold through a third party to Raffaele Riario, a powerful Cardinal in Rome who constructed the Palazzo della Cancelleria.

More of a statesman than a priest, Cardinal Riario was an influential figure throughout the Renaissance. A lover of fine arts and Roman statuary, Riario quickly saw through the Sleeping Eros. While Michelangelo should have incurred the Cardinal’s wrath, he instead earned his respect. “The ability to mimic Roman sculpture was a sign of ability in the Renaissance,” Noah Charney, art history professor and author of The Art of Forgery, explained in a 2016 interview. “In the studio system, which every artist was a part of until the 19th century, your job was to mimic the style of the master—otherwise the works produced by the master’s studio would not look congruous.”

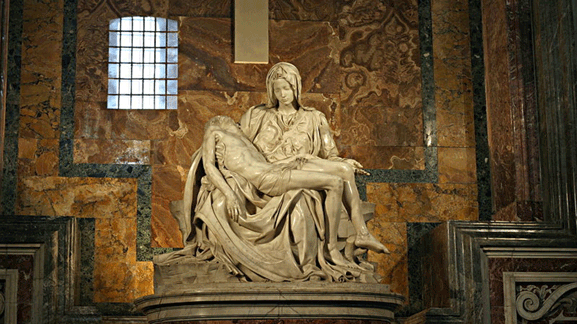

In the end, Riario returned the Sleeping Eros to the aforementioned third party (del Milanese) and praised Michelangelo for his skill. Within a year, Riario commissioned two additional works from the young artist: Standing Eros and Bacchus. Ultimately, the scandal propelled Michelangelo’s career: one year after completing Bacchus, he would be commissioned to complete the Pietà in 1498.

So, whatever happened to the Sleeping Eros? According to The Art Newspaper, the statue gained popularity after Michelangelo unveiled his Pietà. Del Milanese sold it to Cesare Borgia, who then passed it on to Guidobaldo da Montefeltro. Borgia reacquired Eros in 1502 and then sent it as a gift to Isabella d’Este in Mantova. The Sleeping Eros remained in Mantova until it was purchased by King Charles I of England. Unfortunately, the statue went missing in a fire at Whitehall Palace in 1698. While the Standing Eros was also lost to time, Bacchus is currently displayed at the Bargello Museum in Florence.

As for Michelangelo, he never quite gave up forgery. According to his close friend and biographer, Giorgio Vasari, Michelangelo often “…copied drawings of the Old Masters so perfectly that his copies could not be distinguished from the originals, since he smoked and tinted the paper to give it an appearance of age. He was often able to keep the originals and return his copies in their place.”

The legacy of Michelangelo’s forgeries are largely unknown, and his accomplishments as a painter far overshadow his beginnings in mainstream art history. However, his story points to the strange, elusive history of art forgery, and how the practice marries artistic skill with illusion and politics. For more stories of deception and great art, stay tuned for Arts Help’s art forgery series!