Despite a life of crime, the painter Han van Meegeren emerged as a hero in the aftermath of WWII. He didn’t fight against Hitler or Nazi Germany; he never picked up a gun during his life. But van Meegeren was an artist and one who venerated the Old Masters (Da Vinci, Botecelli, Michelangelo). Van Meegeren couldn’t fight, but he could paint.

Born on October 10th, 1889 in the provincial town of Deventer, Henricus Antonius van Meegeren had a difficult childhood. His father was strict and demanding; his mother was emotionally absent. It was not until high school that van Meegeren discovered his own artistic talent, much to the chagrin of his traditional father. van Meegeren became friends with Willem Korteling, the son of a local artist. Korteling’s father took the boy under his wing and taught him the Baroque and Renaissance styles. Van Meregeren also engaged with the art of doodschildering – or creating paints from scratch, with techniques similar to the 17th century. This strange education of the arts would later become instrumental in his forgeries.

While van Meegeren majored in the study of architecture, he practiced visual art throughout his college years. According to biographer H. Kreuger, van Meegeren excelled in college: his grades were outstanding, and his architectural drawings were “more elegant than was necessary.” Despite this natural calling, Meegeren continued to favour painting and became to support himself by creating original works. Unfortunately, van Meegeren was a painter of limited ability, and his pieces attracted few buyers. According to van Meegeren’s 1945 testimony, his first forgery was "spurred by the disappointment of receiving no acknowledgements from artists and critics....I [was] determined to prove my worth as a painter by making a perfect seventeenth-century canvas."

The process of his forgery began with little obstacle. Van Meegeren needed to choose one painter to imitate, one whose style and technique reflected what he learned under Korteling’s tutelage. He chose Johannes Vermeer, a Dutch painter best known for his work “Girl With a Pearl Earring.” That Vermeer only produced 35 or 36 paintings throughout his career proved helpful: van Meegeren only had to imitate a handful of paintings, rather than the hundreds most artists produced throughout their lifetimes.

Van Meegeren’s next challenge was considerably harder. To convince experts that his paintings were over 300 years old, he had to age the paint. First, the paint would have to dry and age. He would also have to imitate craquelure, a fine pattern of cracks in older paints and varnishes. To this end, van Meegeren bought a pizza oven, hoping this would age his paintings. But it only burned or melted the paints. Finally, through extensive experimentation, he stumbled upon the correct recipe. By mixing Bakelite, a type of synthetic resin, with his paints, he could imitate textures without damaging the material.

Early on, van Meegeren had a stroke of genius. Instead of directly copying Vermeer’s work, he would create new pieces that would pass as undiscovered Vermeer’s. It was a risk, but one that paid off handsomely. According to Edward Dolnick, author of The Forger's Spell, van Meegeren realized that, "…a forgery that was close was almost worse than if he hadn't tried at all, because….the experts would focus on the difference between the forgery and the real thing. What turned out to be a much better strategy for van Meegeren was to make a painting that had a few hints of Vermeer but that wasn't like any of the known Vermeers, and then let the experts fill in the gaps themselves."

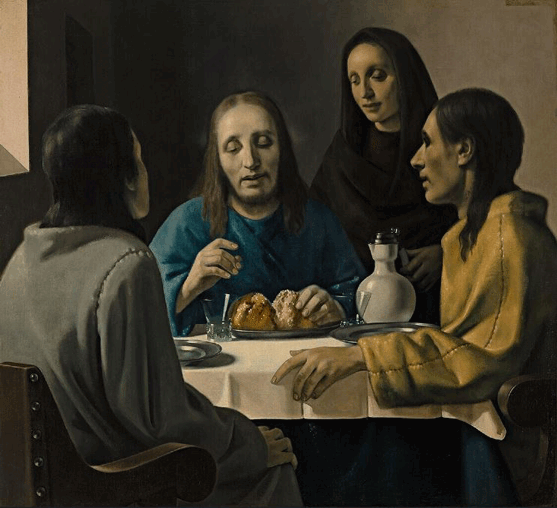

Van Meegeren created his first forgery, The Supper at Emmaus in 1937. While the painting is a direct nod to Carravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus, there are several elements that are distinctly Vermeer. Van Meegeren’s “The Supper at Emmaus” uses rich colours, which were hard to create in the 17th century, along with masterful use of shadows and light. Compared to Vermeer’s other words, like Girl With a Red Hat or The Lacemaker, it was nearly impossible for experts to tell that The Supper at Emmaus was a forgery. A friend brought it to Abraham Bredius, an art critic and world-renowned Vermeer expert at the time. Bredius declared it a genuine Vermeer and said it was “one of the finest of Vermeer’s works” he’d ever seen.

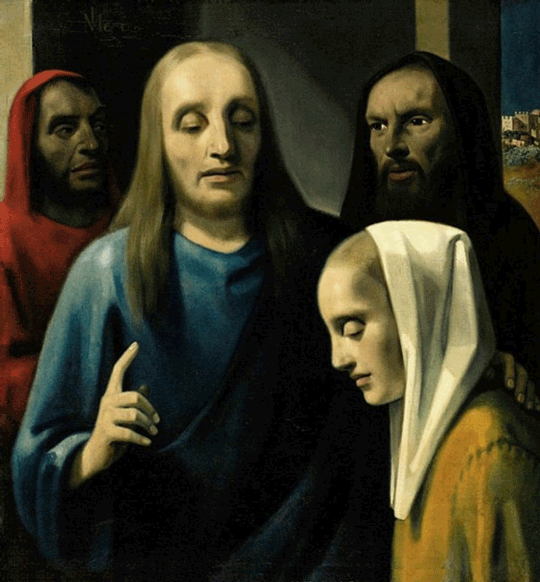

From that point on, van Meegeren focused on creating “original” Vermeers. Throughout his career as a Vermeer forger, he amassed a fortune. It’s estimated that he made somewhere between 5.5 and 7.5 million guilders (or about US $25–30 million today). One of his best customers was Herman Goering, leader of the Luftwaffe and Adolf Hilter’s right man. In 1943, van Meegeren sold another forgery, Christ and the Adultress, to Goering in exchange for 300 Dutch paintings. A year earlier, one of his faux Vermeer’s sold for 1.6 Dutch guilders, and was quickly named one of the most expensive paintings ever sold.

Ultimately, it was van Meegeren’s connection to the Nazis that was his undoing. The Nazis kept meticulous records, and one of Goering’s journals noted that van Meegeren sold him a Vermeer via a third party. According to the University of Glasgow, no one had realized that the Vermeer was a fake, so “Van Meegeren was brought to trial for selling what was then essentially considered to be a national treasure.” At first, the trial was very cut-and-dry. Van Meegeren sold an original Vermeer and engaged in business with the Nazis. If the jury could prove he was guilty, he would be executed.

Then, Van Meegeren gave his testimony. Under oath, he admitted that he did sell Goering a painting, but that the painting was a fake. Throughout his trial, van Meegeren styled himself as a hero and a defender of Dutch culture. Of Goering, he said: “Of course I sold it to Goering, I knew what better person to con than this great Nazi bag of wind. How could a person demonstrate his patriotism, his love of Holland more than I did by conning the great enemy of the Dutch people?”

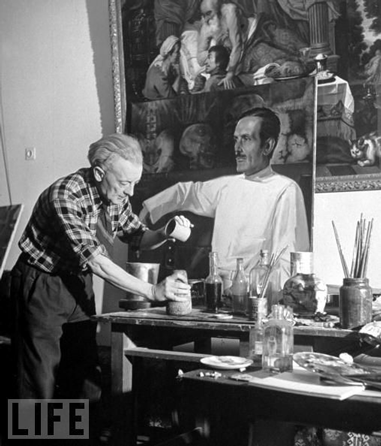

The Dutch people were won over. To them, van Meegeren was a hero who had preserved their culture while swindling the Nazis out of millions. The jury, however, was not convinced. To prove his innocence, the court had van Meegeren paint his last Vermeer - “Jesus Among the Doctors.” In the presence of court-appointed witnesses and several members of the press, van Meegeren used Bakelite and an oven to create, then age, his painting.

According to the New Yorker, the Dutch “craved a carnival” and van Meegeren’s crime “was too pricelessly funny to be marred by stale grudges.” Van Meegeren’s easy charm and affability only helped his case. Once, the judge asked: “You do admit, though, that you sold these pictures for very high prices?” Van Meegeren replied, “I could hardly have done otherwise. Had I sold them for low prices, it would have been obvious they were fake!”

In the end, Van Meegeren was sentenced to one year in prison. However, he died of a heart attack on December 30th, 1947, before he could serve time. Van Meegeren’s legacy is unique: the master forger conned many and created an aura of Vermeer that was so persuasive, it nearly got him killed.